The title “American Splendor” taken by writer Harvey Pekar for his 32-year-long series of autobiographical comics, is a bicentennial joke. The 200th birthday of America looked pretty bad in Cleveland, the buckle on the rust belt.

As the city’s fortunes improved slightly, Pekar’s did also: his marriage of 27 years occurred because he met Joyce Brabner, a fan from Delaware. The story is told in the celebrated movie that’s the perfect intro to Harvey’s life and times, also called American Splendor.

One famous thing about Cleveland: Superman was created there. It doesn’t take much effort to contrast the ideal altruistic superhero and Pekar himself, whose works—whose persona as an artist—exemplified humanity, and warts-and-all storytelling.

Pekar’s work grew with the 1970s, a serious decade in his working-class town. Underground comics, then coming to their close as a popular medium, stressed sex, drugs and escapism.

You’ll find only one sex scene worthy of the name in Pekar’s works, in American Splendor #1 (1976), a story (which Pekar never republished later) about his encounter with a childhood friend who became a prostitute.

Pekar wasn’t a stoner, and he didn’t get out of town much. So most of the time, Pekar’s subject was work—the livelong day of his job as a clerk at a government hospital, the push-and-pull of the relations with the people who worked there; his frustrations at trying to be a writer, of trying to get published and trying to promote his writings. (It was this quality that got Pekar called “a self-promoter” by Robert Christgau—big praise from a writer who trumpets himself as “The Dean of Rock Critics.”)

Pekar originally self-published his work; it got national distribution because of a chance encounter he had with a friend from Hebrew school who owned a comic-book-distribution system. (That’s how I found his work for the first time, in a now-defunct magazine stand in a Jewish neighborhood in L.A. at Pico and Robertson.) Pekar also had a big-name talent aiding him from the beginning; his friendship with Marty Pahls led him to befriend Robert Crumb when Crumb was still an artist for American Greetings.

Before he was internationally famous, Crumb toiled for a couple of years under the direction of his then-boss Tom Wilson, whom Crumb characterized as the creator of “that fucking Ziggy.”

Since they hung out for a while, Pekar got the idea from Crumb’s work of telling his own story.

The collaboration between celebrated cartoonist and Cleveland clerk produced not just some of Pekar’s best work, but some of Crumb’s best work as well. Pekar’s focus on good conversation and pungent silences harmonized with Crumb’s own longings to connect with the class of people who’ll never own a yacht, in Drew Friedman’s phrase. Their senses of humor overlapped, and so did their sense of tragedy and solitude.

Their best work together—collected in the essential book Bob and Harv’s Comics (1996) observe the small talk of Pekar’s fellow employees and a co-worker’s casual mention of a near-death experience. (“I talked, I talked Jesus off the cross … but he shot me anyway.”). It’s likely Crumb never did anything in his career as soulful as the story of Pekar mulling over his own mortality during a Saturday-morning trip to a bakery.

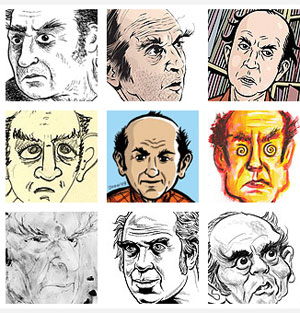

When they stopped working together, Pekar found other collaborators. Despite their wildly different styles of these artists, Pekar became an easily recognizable comic character: a balding elder man with big sideburns and the neck of a white T-shirt showing under his button-down shirt.

Unable to draw much, Pekar storyboarded out stick figure drawings, telling the story of his life; he paid various illustrators to flesh them out, and that’s how we have his story.

He grew up the son of a first-generation Polish-Jewish immigrants who ran a small mom-and-pop grocery store. There were two failed marriages, a year at Case Western University, a stretch in Navy boot camp. In the early 1970s, he made an unhappy trip to Santa Cruz and the Oregon coast.

He also recorded personal moments in his living room—pondering books and jazz records (he was a contributor to Downbeat). Pekar was an autodidact; it’s clear he was intelligent enough for academia, and he was proud of the fact that his father was a Talmudic scholar. But as related in his 2006 memoir The Quitter he got his education through second-hand bookstores and the library.

He was an anxious, argumentative man—a nitpicker who could drive people nuts. He was basically gentle despite a temper for two, as the song goes. It was still a surprise to hear that he was a serious fist-fighter when he was young, when the various turfs of Cleveland were very clearly marked out for the different ethnics who lived there.

But Pekar was always pugnacious and took great satisfaction in trying to keep David Letterman honest during his various trips to New York to do the talk show. Letterman’s scheme seemed to have been to have Pekar as part of his weekly roster of weirdoes, a salt-of-the-earth eccentric from a city that’s better known as a punch line than a place. Pekar outwitted Letterman, preferring to bring home bad news about General Electric’s misdeeds to NBC, the TV station owned by the conglomerate.

Though he delighted in chronicling his neuroses and fears, Pekar was a brave, honorable man. And he was humble. When I praised his work during my single visit to his house in Cleveland Heights in the early 1990s, he cut me off, “I put my pants on one leg at a time, you know?”

Pekar once described the time he had after he recovered from lymphoma in the 1990s as “windfall years.” (He told the story of that illness in the outstanding memoir Our Cancer Year, illustrated by Frank Stack.)

Pekar had a few of those vintage years after the film of American Splendor came out; he had some fame, and got to see a little of the world and a lot of his faithful readers. Pekar, who was concerned about his life and legacy, who thought of himself as a quitter and a nobody, who feared that his life would leave no impression, was mourned worldwide by fans.

Many-Splendored Man

Harvey Pekar, creator of ‘American Splendor’ comics, talks about live in Cleveland and his Almost All-Expenses-Paid Vacation to Hollywood

Students for a Democratic Society

A Graphic History

Joyce on a Mission

Samuel Ornitz–novelist and blacklisted screenwriter–was an unsung pioneer of stream of consciousness

A Writer With Qualities

The restoration of Robert Musil’s epic novel ‘The Man Without Qualities’

Got the Milkman?

David Boswell brings fabled ‘Reid Fleming’ back to life

The Sun Ra Also Rises

Local label explores the jazz avant-garde from Evan Parker and Beth Custer to a new Sun Ra tribute

Russian Escape Artist

Novella author Vladimir Makanin finds no solace in the near future

Twinned Vision

A new boxed set showcases the Miles Davis and Gil Evans collaboration

Book Review: Slice of Gay Life

Alison Bechdel writes as well as she draws

The Beat Master

Herbert Huncke, the unsung Beat, finally gets his due

Magical Mexican

In ‘Palinuro of Mexico,’ Fernando del Paso folds James Joyce into magical realism

Clear as a Clarinet

Jazzman Don Byron re-creates some big-band concepts and weaves modern improvisations on three eclectic new releases

A View of Debut

A new reissue chronicles Debut Records’ jazz highlights of the 1950s

Taking Flight

Spanish Fly creates tomorrow’s sounds from today’s instruments

Cleveland to Sundance

How alternative comic-book pioneer Harvey Pekar finally hit the big screen