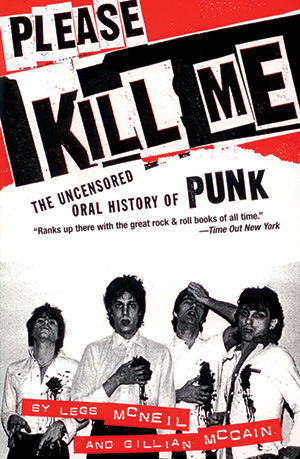

In much the same way that punk was a musical revolution, the definitive book about punk was a literary one. With its modernization of the oral history tradition—telling its 424-page story entirely in a string of quotes that form a solid, winding narrative—it’s practically impossible to overstate the degree to which Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk revolutionized both the book industry and the way we think about storytelling when it was published in 1996.

Despite its gritty, grimy subject matter (or, more accurately, because of it), Please Kill Me was sublimely elegant in the way it matched form to content. Finally, here was a book about punk that reflected the actual spirit of the movement by representing its subjects’ words as directly as possible, with a minimum of filters or interference from the authors. It took nonfiction back to its primal urges.

Perhaps the book’s mix of iconoclasm and literary ambition makes sense considering it was co-authored by two writers with very different backgrounds, but a surprising like-mindedness. One, Legs McNeil, is the man some credit with giving punk music its name in the first place, when he christened Punk magazine in 1975. He started it with cartoonist John Holmstrom and publisher Ged Dunn, providing the fledgling New York scene led by the Ramones, Patti Smith and Richard Hell (and eventually also British bands like the Sex Pistols) with a unifying concept. His co-author, Gillian McCain, was the program coordinator of the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church—famed for its connections to Smith, Jim Carroll, William Burroughs and other punk poets beginning in the 1970s—from 1991 to 1995, roughly the same time that they worked on Please Kill Me.

After hundreds of interviews with everyone from icons like Lou Reed and Iggy Pop to lesser-known scene stealers like former “company freak” record exec Danny Fields and filmmaker Bob Gruen, the result was the best-selling book ever about punk music, which has been published in 15 languages.

Now, as Grove Atlantic prepares a 20th anniversary edition of Please Kill Me, the book has spawned literally hundreds of imitators, everything from similarly focused music books like We Got the Neutron Bomb: The Untold Story of L.A. Punk, Grunge Is Dead: The Oral History of Seattle Rock Music and Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal to general pop culture megahits like Live From New York: An Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live by Tom Shales and Andrew James Miller and their follow-up Those Guys Have All The Fun: Inside the World of ESPN. The oral history craze has reached such a fever pitch—and, perhaps, level of absurdity—that the July issue of Vanity Fair featured the “definitive oral history” of the movie Clueless.

So why isn’t Legs McNeil proud of blazing a trail for this new wave of 21st century oral histories?

“They sucked,” says McNeil by phone from L.A., where he and McCain are working on a new oral history book about the ’60s rock scene there. “I wish someone would do a good oral history. At least as good as Please Kill Me, you know?” McCain, on the same phone call, is more diplomatic. “When I look at just the punk books that have come out as oral histories, not even oral history music books, I think there’s a hundred, literally. It’s just unbelievable,” she says. “So Legs may not be proud that we were the trailblazers, but I am.”

McNeil’s stance may sound like punk posturing, but actually the pair adhered to some strict rules while doing Please Kill Me that later imitators have often ignored, usually to their detriment.

“We refuse to cheat,” says McCain, “where we’d have a piece of prose in between two people talking. ‘And then so and so went to blah blah blah.’ To me, that’s cheating.”

McNeil says the demanding structure of oral histories is what makes them so easy to screw up. With no exposition to support them, the quotes have to weave a tight narrative.

“They’re really difficult,” he says. “Oral histories are like rock and roll itself—very, very fascistic and anal. Seriously. Once you break the formula, no matter what you’ve done up till that point, the whole thing falls apart. It’s not like you can make a mistake. You know, like in memoirs there are shitty chapters where the guy goes off on his cat or his mother or something, and you go with that because it’s going to get good again. But in an oral history you can’t have that, because it’ll collapse.”

Please Kill Me established a blueprint for understanding the punk movement that has been followed by almost every book since, with the Velvet Underground as the first real protopunk band, and Lou Reed as the godfather of punk. While the Velvets were already widely accepted as punk progenitors by the ’90s (with no small amount of credit going to the 1990 cover album Between Heaven and Hell: A Tribute to the Velvet Underground, which kicked off the tribute record craze) the actual story of how punk evolved from band to band through New York and Detroit had never really been told.

But the book’s framing device—beginning with the Velvet Underground starting out in Andy Warhol’s Factory scene, and ending with their reunion in 1992—was something that developed over time. Finding such a framework was key, since the origins of punk could be said to stretch all the way back to the beginning of rock itself. Just look at how the Sex Pistols worshipped Eddie Cochran, or the Cramps covered the Johnny Burnette Trio and the Count Five.

“It wasn’t easy, because we started interviewing people from [’60s garage band] ? and the Mysterians,” says McCain. “So we weren’t sure we weren’t going to go that avenue, but it ended up we didn’t. There’s so many garage bands. And the people around the Velvet Underground were in the narrative later, so they were part of this intertwining—with Iggy, and Lou on the cover of Punk magazine. But with the garage bands, there was no interconnectedness.”

“What we did in Please Kill Me was we showed the linkage from the Velvet Underground to the Stooges,” says McNeil. “Nico moves in with Iggy, John Cale produces Iggy’s first album. We kind of mapped it all out, and every punk book has taken that formula. And no one has ever said ‘hey, thanks for connecting the dots!'”

“I think a lot of people give us credit,” counters McCain. “Often in the acknowledgements, they’ll say ‘We want to thank Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain for turning us on to this format.”

“Well,” grumbles McNeil, “maybe they should have bought us dinner.”…