HERE’S A VITAL ISSUE under discussion (at last) on both sides of the Atlantic. Governments, rich and poor, urgently need two things: a method to calm speculation in the financial markets and new ways to raise revenue.

In late 2011, the European Commission proposed a tax or fee on financial transactions. This move appears to be part of the newly announced European Union plan, with Britain the sole dissenter.

The idea was endorsed in an op-ed piece in The New York Times on Sept. 28, 2011, by Philippe Douste-Blazey, a former French foreign minister.

Douste-Blazey laid out the basics: “A tax of just 0.05 percent levied on each stock, bond, derivative or currency transaction would be aimed at financial institutions’ casino-style trading, which helped precipitate the economic crisis. Because these markets are so vast, the fee could raise hundreds of billions of dollars a year globally for cash-strapped governments and could increase development aid.”

Read the article. But note that it does not mention the top reason for such a tax—that it might benefit real human investors by slowing finance and equity trading back down to the speed of human thought.

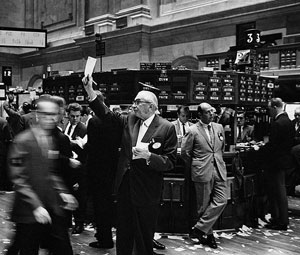

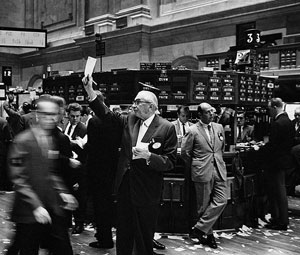

We’ve come a long way, in our modern world, since Grampa used to drop by his stockbroker once-a-month, clutching some news articles, intent on buying a few blue chip shares of IBM or Kodak or Polaroid.

Today, things are both better and worse for private investors. You can do your deeply considered stock or commodities trades over the Internet, at much lower commission rates than in those olden times. And a serious day-trader has access to lots more information.

Has this shifted the advantage in favor of the little guy? Hardly. The big boys on Wall Street have computers, too, and faster Internet access than you can afford. Sophisticated software lets them track the orders and activities of millions of market participants in fractions of seconds and leap upon opportunities to profit from the predicted actions of others.

Now, in fairness, these practices do have defenders who cite a rationalization called “market efficiency.” According to this liturgy, any process or innovation that allows ever-smaller increments of trade to happen ever faster will automatically lead to better allocation of society’s capital, and thus a skyrocketing economy.

As incantation/rationalizations go, this is a doozy. Some very high-IQ boffins recite it with the hushed reverence of medieval monks—despite the fact that almost no reputable economists support it. More significantly, the flourishing of fast-cybernetic trading has directly correlated with the steepest decline in the health of capital markets in a century.

Indeed, the increase in market volatility that we have seen lately, with sudden spikes in apparently random directions, can be generally attributed to this trend. When asked to appraise why markets experience sudden crashes without any apparent reason, Wall Street analyst Peter Cohan explained the reason such things are happening more often, and in wilder swings:

“… 70 percent of the volume of trading on the stock exchanges these days is done by something called flash traders, and that’s basically computers that buy and sell stocks and hold them for about 11 seconds on average. So all of the discussions that we have [about] the economy, politics, regulations, company earnings—all that stuff—there’s just no way that a computer holding and selling a stock in 11 seconds is going to be able to do all of that analysis. So it’s really all out the window. And there’s really no clear-cut explanation for why stocks move up and down every day.”

Flash-trading not only gives major houses an advantage in the short term, it has exacerbated the problem of bubbles—in which market trends get amplified and inflated, propelling massive swings of capital that have nothing to do with the needs of real businesses or real consumers.

Take a Seat

Then there is the small matter of “seating.” Historically, stock markets (and bourses, or exchanges, for commodities and credit instruments) began with some fellows gathering at an inn or under a tree to regularly sell or trade share certificates with each other, or on behalf of other folks.

When this trading became big business and moved into dedicated buildings, these members held “seats” and practiced the standard methods of guilds everywhere, limiting who could come to the table and buy or sell.

All outsiders had to hire seated members to trade for them, while paying commissions—collusive club practices that have been banned (as recommended by Adam Smith) in most other parts of the economy.

Yes, a little market competition arrived recently, as E-Trade and other online member-brokers slashed commission prices for retail folks like you and me. New electronic methods made that possible. But, also, the sheer volume of retail trading increased greatly, making up the difference. So the firms profited overall.

What the seated members don’t want us to notice is that flash-computerized trading gives them a new, incredible insider advantage. Even if you or I had a computer and program as good as the systems owned by Goldman-Sachs, we could never do what they do, because they are on the inside, making millions of flash trades for free.

You, on the other hand, would pay a commission on every flash trade and—no matter how advanced or clever or wise your program—you would lose.

In other words, the Transaction Tax proposed by the Europeans and others already exists. It is levied by members of an insider-guild elite who use it to prevent anybody else from doing what they can do with new technology.

This is not “market efficiency.” It is the kind of market-warping influence manipulation that Adam Smith despised.

But absolute refutation of the “efficiency” argument comes from a different direction: from physics, biology and thermodynamics.

Computers and Markets Emulate Life

Living creatures thrive by finding a steep gradient—or sloped difference—of usable energy. Green plants utilize the fact that incoming sunlight is thermodynamically clean and much less entropic (filled with entropy) than the surrounding environment. (Greenhouse retention of Earth’s infrared radiation is thus intrinsically entropic.)

Some of this gradient is used by the plant to grow and reproduce, or else gets stored away, while some is lost as a transaction cost.

Animals in turn consume plants to take advantage of that stored useful energy, investing the time and effort to bite and chew and digest in order to benefit from some of the remaining gradient.

Predators then pounce and bite and digest in the next stage. There are always losses with each transaction, hence the number of predators who can be supported at each scale gets smaller and smaller.

Each plant, herbivore and carnivore also has parasites, intestinal worms and bacteria, etc., who grab some of that stored energy along the way. If they steal too much, the animal can’t get a steep enough or plentiful enough energy gradient, and it dies.

Can you see it yet? Beyond a certain level, increasing the total number of transactions does not make living systems more efficient. It flattens all energy gradients and makes life unhealthy … even dead.

Oh, I can hear the objections. “Biology has no relevance to economics and finance.” Well, we could argue about that endlessly, but it doesn’t matter, because entropy—indeed, all of the things I described above, like energy gradients—are vital factors in modern information theory. And information theory is the exact basis that fast-traders claim to have underlying everything they do.

They bandy words like “thermodynamics” with great abandon. But it is lip service.

Returning to Capitalism

Yes, the existence of a stock market does create a habitat-ecology for living companies to compete, to form alliances, to prey on each other, to seek out the capital they need in order to grow.

Stock markets are vastly overrated in the last category, since companies themselves benefit very little from wild swings in share price, except when offering new shares.

(There should be substantial difference in the capital-gains tax for new shares than there is for gains in the simple trading of old shares, an activity that only helps capitalism at very low efficiency.)

Still, you do get synergies that show how Wall Street can and does serve Main Street. When a human investor looks at a company’s new product and bets that “this new gizmo or service is gonna go big!” and orders 1,000 shares on E-Trade, at a low commission, then there’s a good chance that capital will flow to a place that can benefit and use it, all motivated by the hope of a nice profit “meal.”

Buyers always believe that the “true” value of the share is higher than the seller thinks, and yes, one of them will be proved wrong. That is the Darwinistic aspect of equities markets. No one’s heart should bleed.

Indeed, under certain conditions—when all the players are getting fair access to all the information that they need and nobody’s doing insider deals—it is good.

Can the same be said of computerized flash programs that dive in and pounce on any detected market trend, making millions of automatic trades, detecting or anticipating the decisions of human traders? Somebody is making lots of money. Is it the actual buyers and sellers of equities or the companies involved?

This very year, a whole new, super-fast transatlantic fiber cable is being laid, with just one purpose—enabling a few brokerage firms to gain a couple milliseconds advantage in flash-trading; they’ll make billions. But do you see how that helps our market economy? I can’t.

The Supreme Rationalization

Here is the core article of faith among those pushing flash trading, as expressed to me in a note from a senior Wall Street partner. (Who happens to like my books.)

“There is a gap between the perceived value of the stock as desired by the buyer and perceived by the seller. That means the true and correct value isn’t being accurately pegged. By jumping in between buyer and seller, we help eliminate this gap, causing the inefficient disparity to go away, helping the market settle on the true price.”

Yee-god. Did you grasp that? He admits that he makes his living by leaping between buyer and seller, snapping up the value gradient that motivated the buyer to make an offer in the first place.

And he manages to rationalize that he is doing a “good” thing. Good for buyer and seller. Good for markets. Good for capitalism. Good for himself. Well … one of the above.

Some have likened the ruthless voracity of these trading systems to the “tragedy of the commons.” Others suspiciously see the blizzard of computer trading as a way to create a vast fog behind which a few thousand oligarch golf buddies can hide insider deals. Both views have some merit. But there is another that goes deeper to the heart-essence of the matter.

Want the exact parallel in nature? It is those gut parasites or E. coli or salmonella or typhus that nibble away at the gradient of energy in the meals that an animal consumes—or the gradient of potential profit that the human trader perceives between the current asking price and what he or she feels the stock may soon be worth.

It is the core logic of parasitism. If you ever read Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, these are the perfect passengers aboard the Golgafrincham B-Ark.

Hence, my complaint about the proposed transaction tax or fee is that it is being justified for the wrong reasons. Sure it will bring in revenue from the sector of the economy that made huge bonuses while wrecking our economy.

And yes, it will damp down the speculative swings that have made equities markets wildly unpredictable and dangerous for human investors. Such a fee will restore an emphasis on those providing new, competitively innovative goods and services.

But the biggest reason is that human investors won’t care about—or even be aware of—a small, say 0.1 percent, trade fee.

But those computerized parasitical systems will howl in agony. Thus the transaction fee will give you a better chance to gain from your own savvy and insight when you log into your E-Trade account.

The Past and The Future

In fact, this kind of tax or fee is well-precedented, with plenty of history and tradition behind it. Enacted to help pay for World War I, the “Securities Turnover Excise Tax,” or STET, worked just fine in the United States from 1914 to 1966.

From 1960 to 1966, stocks were taxed at the rate of 0.1 percent at issuance and 0.04 percent on transfer. Bonds were taxed at the rate of 0.11 percent at issuance and 0.05 percent at transfer.

Indeed, there is a way that conservatives might be able to rationalize a “fee” instead of a “tax,” if all of the funds that it generated went first into paying the expenses of the S.E.C., the various insurance programs and other regulatory apparatus that they rely upon for the smooth functioning of their markets. (Thus removing these entities from the shoulders of the public treasury.) It can be viewed as a basic pay-to-play, and thus not a tax at all.

Insurance funds could be greatly expanded to provide a cushion against the next market contortion. Especially, funds could be spent on balancing and fairness on the international scene.

In fact, there are some even in the Belly of the Beast who have come around to supporting a return to this sensible measure.

For example, David Harding, CEO of Winton Capital, a $26 billion hedge fund, the world’s largest quantitative-calculation, or quant-based, fund, was quoted in the Financial Times: “I would be in favor of a low [financial transaction tax] if part of it was used to finance more supra-national regulation of markets.”

Moreover, such a fee is already the norm in most advanced countries. The EU is apparently instituting a STET across the board in the Eurozone, and Britain, whose “city” bankers rule the roost, nevertheless has a STET.

For comparison, the U.K.’s STET is about .25 percent, and Taiwan just dropped theirs from .60 to .30 percent. Hong Kong and Singapore, the two countries that score highest on the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, also impose transaction fees.

Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) and Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.) recently introduced The Wall Street Trading and Speculators Tax Act, which would impose a minuscule tax of 0.03 percent on financial transactions, meaning that long-term investors would barely notice it. Even so, it could raise more than $350 billion to reduce the budget deficit over the next nine years, according to an analysis by the Joint Tax Committee, a nonpartisan congressional scorekeeping panel.

The Real Reason to Worry

So, what does all of this have to do with The Terminator? (OK, I saved the sci-fi perspective till last. But it has a terrifying kind of plausibility.)

You’ll recall the by-now cliched premise of that film—it supposes that (sometime in the future) the U.S. military would develop a super computer/program/system called “Skynet” that gradually becomes self-aware through a process that theoreticians call “emergence from complexity.”

This idea is actually taken very seriously by deep thinkers about artificial Intelligence. Indeed, our first encounter with AI may come exactly that way … by surprise.

Only—supposing that this malevolent AI comes from a military source? That’s pure Hollywood. Military AI systems are built with high priority to systematic reporting, accountability, multiple redundancies, fail-safes and obedience to chain of command.

No, there are other complex computer systems that seem far more likely to suddenly become self-aware in powerfully dangerous ways.

Take those high-speed trading systems we’ve been discussing. They are growing incredibly sophisticated, at a very rapid rate, absorbing and incorporating models of human psychology, with one goal in mind: To appraise and predict behavior patterns in order for the program to track and to pounce on opportunities for predatory trading.

Competitive ferocity is the only criterion for success. Indeed, if you were to even propose inserting balancing factors like ethics or morality or accountability into such a project, you’d at-minimum be laughed down and probably fired.

A bizarre sci-fi notion? MIT researcher Alexander Wissner-Gross suggested that the first true AI could emerge on a planetary scale from the developing system of interlocked exchanges for high-frequency financial trading, which could be seen as a developing global “brain” already operating at relativistic speeds.

Moreover, these systems are receiving billions in funding (including their own new transatlantic fiber cable) entirely in secret. There are no public agencies involved. No third-party observers. No Congressional oversight committees. No supervision whatsoever.

Laboratories developing new genetic strains of wheat are under closer accountability than cryptic Wall Street think tanks that may unleash the first fully autonomous AI—programmed deliberately to have only the behavior patterns, goals, attitudes and morality of parasites.

And so we see the ultimate reason to demand a Transaction Fee. At low levels, it would never bother private citizens optimizing their portfolios on E-Trade, especially if each trader gets a hundred or so “freebies” each year that come exempt from the tax.

But it would remove the incentives that Wall Street “geniuses” now feel compelled by, to invest in these monstrous, hyper-fast trading programs that swamp the market in a blizzard of uncountable mosquito bites.

The fee (which could also help balance our budget) can be tuned to give that human a fighting chance and to discourage the very worst kind of artificial intelligence from leaping upon our necks out of the dark.

Copyright © 2011. All rights reserved.

David Brin is a scientist and author whose future-oriented novels include ‘Earth,’ ‘The Postman’ and Hugo Award winners ‘Startide Rising’ and ‘The Uplift War.’ Brin is also known as a leading commentator on technological trends. His nonfiction book—’The Transparent Society’—won the Freedom of Speech Award of the American Library Association. Brin’s newest novel, ‘EXISTENCE,’ explores the minefield of survival that confronts any intelligent species. It will be published by Tor Books in June. He can be found on the web at www.davidbrin.com.

Footnotes

* In fairness, here is a report written by a finance industry think tank attempting to rebut the notion of transaction tax. It appears to make precisely the “efficiency” arguments I predicted. Go ahead and hear the other side out. Only remember, it all boils down to “supply side” mysticism that has never, ever seen any of its large scale predictions come true.

In any event, it seems that the experiment will be run, if the new EU arrangements do include (as I’ve heard) a transaction fee. One reason that the British government (largely swayed by the “City” banks and trading firms) opted out.

**One expert wrote in, supporting the STET with a series of sample portfolio experiments, showing that any human trader will see almost no inconvenience of “friction” but that flash predatory programs would lose their advantage:

“Now compare this to the cost of the transaction taxes. In my own case, my most frequently traded portfolio is once a month. A .05 percent tax would amount to a 1.0005^12 or .6% drag on my Compound Annual Growth Rate. For my quarterly and annual portfolios, the numbers are .2 percent and .05 percent respectively. I would point out that this is small compared to the reduction in drag that came from decimalization that happened after I started running this portfolio.

“The useful thing is that this drag increases exponentially with trading frequency. Trade 1,000 times and the drag is 64 percent; 10,000 times and it is 14,800 percent; a million times and my calculator overflowed. This means that even if you deem .6 percent too onerous for the monthly trader, you could go to .005% and the 64% bite occurs at the 10,000 trade level and 14,800 percent at 100,000 trades and now you can calculate that a million trades will give you a drag of 5*10^23% all while costing me 0.06% a year on my monthly.

“You could even feed this money into the Securities Investor Protection Corporation so that this provides additional counterpart protection as compensation for the minor sums being charged to the low-frequency trader. I would argue that any putative efficiency gain from high-frequency fully automated trading is more than outweighed by the systemic risks of putting the financial system largely in the care of systems whose behavior cannot be comprehensively understood, much less predicted. That this can be limited while imposing essentially zero net cost on retail investors strongly argues for doing so.”