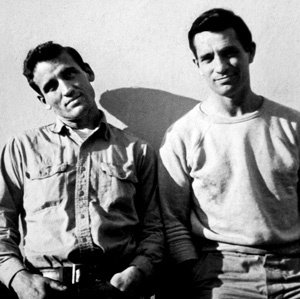

The Man

No need to revise the standard view of Kerouac as a tragic figure, to ignore the surfeit of drink that diluted a writer’s talent. Whether he liked it or not, Kerouac was the front man for “The Beat Generation”—a marketers’ wet dream of pointy beards, berets and septic (and overpriced) coffeehouses.

Thus Kerouac was often too popular to be respected, and was a pinata to be walloped by rival literary figures from John Updike to Steve Allen. Less well-known than the famous thirst is Kerouac’s achievement at being an ESL writer, since he was French-speaking until deep in his childhood.

Happily, the film emphasizes the serious prose apprenticeship, the love for Thomas Wolfe and Marcel Proust, which preceded Kerouac’s scatting and bopping in print. There are those who still those who say Kerouac’s Wolfe-influenced novel The Town and the City is his best.

Kerouac’s grim side was worsened by the idea that “the wrong son died,” as the running joke in the movie Walk Hard has it. He was haunted by his brother’s death at an early age. He was a born-again Buddhist who never shook the old-school Catholic worship of (in his words) “little lamby Jesus.”

He dwelt in the shadow of his bigoted French-Canadian mother, a woman as tough as the army boots she used to make in the factory. Kerouac was a football player who dropped out, a macho with a taste for bisexual experimentation.

He was, above all, a sufferer of the typical malaise of Depression-era kids who went into the arts: the inner terror that he was, despite all the admiration and all the love, at bottom, a bum. The movie mentions Paradise’s father scorning him on his deathbed for having uncalloused hands.

On The Road covers a small period in the late 1940s when Kerouac crisscrossed the United States by thumb, or more often by bus or drive-away rental: New York/Bay Area/Mexico City via Denver and New Orleans. These were the freest years in Kerouac’s life, before mad fame, the final crash and the sodden last decade in Florida.