Wherever James Franco goes in 2014, he’ll be hard pressed to top last year’s string of achievements. January 2014 started with the unleashing of a brace of Franco films at Sundance: one was a short from the anthology Red Dog/Black Dog, the other the biopic Bukowski about the wastrel poet of Los Angeles. Last year, he starred in the hit film Oz: The Great and Powerful which made $493 million worldwide, while simultaneously winning the San Francisco Film Critics’ ballot as the steel-toothed pimp Alien in the micro-budgeted Spring Breakers. And he also released Interior: Leather Bar through his production company Rabbit Bandini (John Updike, meet John Fante).

Franco has been teaching journalism, writing short stories, painting, getting a grad degree at Yale. He’s made time for a Comedy Central roast, where he sat on a dais enduring jokes of the quality of, “Your pal Jonah Hill? He sure is a fat chowhound!” and “RU Gay, LOL?” In his defense Franco claimed that his appearance was a performance piece. Which is what he also said about a stretch on TV’s General Hospital. Between 2009 and 2012, he made intermittent appearances as the reflexively named Franco, a multimedia artist and serial killer, on the soap (even his characters are multi-taskers).

Having some spare time somewhere, Franco went on Indiegogo to raise money for a series of three short films titled Yosemite, Memoria and Killing the Animals, based on his short stories about Palo Alto.

Yosemite is in post-production now after filming on location in Yosemite Valley and Palo Alto. Many a less literal person could have shot it in L.A., hoping Southern California and Northern California suburbia looked close enough alike enough for jazz. Franco seems drawn back here: trying to get something he left behind in his youth in the 1990s in Palo Alto. Even at the time of his appearance hosting the Oscars in 2011, he came back to the Palo Alto Children’s Theater to meet young fans and make yet another film, a documentary about his mother’s play Metamorphosis: Junior Year. What draws Franco back here?

Take the indefinite article in the title of A California Childhood (2013, San Rafael’s Insight Editions). It suggests Franco’s life could be your California youth. He is quick to acknowledge his privilege, growing up on one side of the racially divided Palo Alto/East Palo Alto split. “We never had any black friendsÉbut we loved black rappers.” On all sides, the people in the bungalows near his house were gearing up for what would be Silicon Valley.

Franco writes: “I use childhood, teenagers and school as forms. For me the particular of the time and place of my own childhood are placeholders for anyone’s experiences at that ageÉ” Franco goes on to cite Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause, and that film’s artistic choice to remove economic class as an explanation of why kids go wild. None of that “depraved on account we’re deprived” stuff. It is the same bypass of the obvious diagnosis that Franco’s later director Harmony Korine used in his script for Kids.

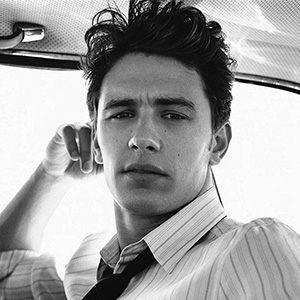

Rebel Without a Cause means a lot to Franco. Franco directed a film, Sal, about the last day in the life of actor Sal Mineo, the co-star of Rebel. On the end papers of the front cover of A California Childhood is a felt-tipped-pen-written list of art, films and places that influenced him, like the list a high school kid makes in his notebook. On the left bottom corner of honor is the name “James Dean”— whom Franco was to play in a made-for-TV biopic. See James Franco and recall that deputy’s line in Terrence Malick’s Badlands: “I’ll kiss your ass if he don’t look like James Dean.”