A young child born in 1929, the product of a strained marriage, is shuttled around Northern California. She knows no real stability until 1939, when her mother, finally divorced, moves to San Jose. The child attends Alum Rock Union School, excelling in art classes, then moves on to San Jose High School.

Although, years later in an oral history, she remembers San Jose as an “cultural desert,” the girl learns a great deal about art from a neighbor who is a commercial artist and from one of her teachers at San Jose High, who “was an absolute inspiration to me.” After a few art classes at San Jose State, she enrolls at UC-Berkeley.

That’s not much time—maybe six or seven years—across a lifetime, but they were formative years for Jay DeFeo, easily the most famous visual artist the city has fostered. Her biography has taken on a life of its own, sometimes bolstering, other times hampering, critical appraisal of her achievements. A new retrospective at SFMOMA brings together for the first time significant examples of her work and makes a powerful case for elevating her to the top ranks of post–World War II American artists.

Starting in the late 1940s, DeFeo established herself as part of the Bay Area abstract expressionism movement. Early pieces, like Untitled (Florence), 1952, feature dynamic passages of bold colors anchored by simple geometric gestures. Later, she shifted to a monochromatic palette. The large canvas Untitled (Everest), 1955, builds from a smooth gray bottom section into a flurry of blacks and whites applied vigorously in overlapping waves like roiling clouds announcing a storm.

More controlled but just as action-filled is Origin, 1956, a tightly bunched series of narrow vertical strokes of black and gray—the painting is poised between a upward thrusts, like jets in a fountain, and a downward crashing, like a great falls pouring over a rock rim. Her work echoes and equals that of several major figures from the period: early Diebenkorn, Hassel Smith, Clyfford Still and Frank Lobdell.

The exhibit also shows DeFeo’s forays into other media. She fashioned oddly crude wood and plaster sculptures of crosses and primitive totemic creatures (which influenced Manuel Neri). She made meticulous charcoal drawings in which fine waving and spiraling lines course through blank space. She experimented with collages of found images in the manner of fellow San Franciscan Jess.

In the late ’50s, DeFeo embarked on a series of large paintings distinguished by the dense application, with a palette knife, of oil paints. These works take on a 3-D aspect, as much sculpture as painting. In The Jewel, 1952, a vertical starburst pattern of heavily caked paint converges across a spectrum of dark reds to a dazzling white center. Along the vertical axis, the paint has been cracked open to reveal deep fissures, as if bones has been pulverized to get at the marrow.

These major works are mere preludes, however, to the piece that came to dominate DeFeo’s life: The Rose. Beginning in 1958, DeFeo devoted herself almost exclusively to the creation of this immense painting. It took over her apartment on Fillmore Street that she shared with her artist husband, Wally Hedrick. Taking up again the starburst pattern of The Jewel, she made it rounder. From a concave center point (located at just about eye level), the incised rays jet outward, growing thicker and more clotted until they disintegrate into blobs of gray and black. Carefully positioned in a special alcove at the museum, The Rose is a riveting, transcendent work—a grand vision of creation or universal flux. Photographs don’t do it justice; the scale and physicality have to be seen in person.

The arduous process of creating The Rose became the stuff of legend. DeFeo built up and tore down the work over and over again. She applied so much paint that The Rose ending up weighing more than a ton. San Francisco’s Beat-era poets and artists often visited her apartment and witnessed the extended birth pangs of the painting. When Jay and Wally were evicted, the moving of the painting was an engineering feat, memorialized in Bruce Conner’s short film The White Rose.

After nearly eight years, The Rose finally consumed its creator. DeFeo, who had an instinct for self-mythologizing, posed half-nude for photographs in front the painting, as if she were a priestess instead of just a painter. The years of labor hindered her career; instead of following up on her first show in New York, she retreated to work on it. After The Rose was completed, her marriage ended, and she suffered from terrible gum problems, which she attributed to years working with toxic paints.

Finally, The Rose had a showing in Pasadena, and then no one knew what to do with it. The Rose ended up at the San Francisco Art Institute, only to be covered by a wall of plaster. It was unseen for two decades until finally rescued and moved to the Whitney in New York. DeFeo did not paint again for several years, retreating to a rural farmhouse in Larkspur.

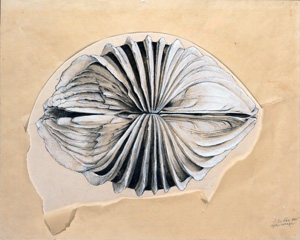

For many art historians, The Rose is a splendid climax with no second act. But the exhibit documents DeFeo’s return to significant artmaking in a variety of styles and techniques. After Image (1970) is a splendid graphite and gouache drawing of a strange shell form with spiral ridges. DeFeo mounted it with a piece of torn paper on top as if the shell had been hidden for many years and only recently exposed to view—surely a comment on her own resurgence.

DeFeo began using acrylics and synthetic paints, believing them to be safer for her health. The best of her works from the mid-’70s, Cabbage Rose, looks deep into the heart of some sooty-white and deep gray leaf forms to a center passage of pure black, so dark, so shiny that it acts as a mirror reflecting the shadows of viewers.

She took up photography, proving to be extremely adept at both traditional gelatin silver printing and in the use of alternative, cameraless techniques like photograms. She worked, somewhat obsessively, on large pencil drawings of mechanical objects (most frequently, a camera tripod and a pair of diving goggles), rendering them at large scale, but rarely as complete things; instead, the lines often fade off into emptiness.

Near the end of her life (she died of cancer in 1989), DeFeo produced several small abstract paintings that are a revelation. Using linen with very thick stretchers, DeFeo painted both the surface and the edges—again, in a subtle way, combining painting with sculpture. The color scheme is lighter, the brushstrokes assured but not tempestuous. In Blue One (1989), a smooth pastel blue meets a swath of swirling white and a rectangle of light gray. The simplicity is breathtaking.

(The show is accompanied by a compendious catalog by Dana Miller, from Yale University Press, which comprises everything in the show and some intriguing pieces not on display.)

Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective

Runs through Feb. 3