Beneath the “In Popular Culture” section of the city of Milpitas’s Wikipedia page are three lone works of art: two films and a novel. At the present moment, in the eyes of the internet’s preferred encyclopedia, this seems to make up the entirety of the cultural footprint of Milpitas. The films are The Milpitas Monster and River’s Edge, made in the 1970s and ‘80s, respectively.

The novel, Devil House, by musician and author John Darnielle, was just released this January.

Darnielle, best known as the founding member of beloved indie rock troubadours The Mountain Goats, has built his Milpitas novel on a tender, unsettled foundation—both the joy and the trauma of what came before. That his book sits next to both The Milpitas Monster and River’s Edge online is not coincidental: both are key to the existence of Devil House, a mise-en-abyme in the guise of a true-crime thriller.

Within the blood-spattered walls of Devil House secrets lurk, many of which remain hidden until the novel’s final, desperate pages. But John Darnielle has his own secret, albeit a less blood-spattered secret: a connection to the quiet Santa Clara city that stretches all the way back to the 1970s.

LITTLE FIELDS

With its “In Popular Culture” list consisting of two borderline-horror movies and one borderline-horror novel, one might conclude Milpitas is a strange place indeed. While for the kids who grow up in its suburban homes, Milpitas might seem like any town in America, it is certainly not without its quirks. The ancestral Ohlone land named after the Nahuatl word for “little corn fields” was once a rich trading post, then, after colonization, a regular stop along trade lines.

Today, a Revolutionary War Minuteman statue stands outside City Hall to commemorate the great victory of not-getting-annexed by San Jose. Sadly, the city’s most famous landmark is the dump. It is, however, rich in cultural diversity. As of the 2021 census, a full 66.9% of the population identify as Asian. The city also boasts one of two Jain temples in California, an incredibly important cultural hub for the area’s South Asian population. The Ford plant that was once the lifeblood of the city (and the main reason Milpitas was incorporated into Santa Clara County) became the Great Mall, which sits adjacent to Elmwood Correctional Facility, the county jail.

“Obviously, no city would want to have a jail within its confines, but we’ve grown accustomed to it,” former Milpitas Councilman Bob Livengood told the Mercury News in 2006. “Elmwood is kind of like the crazy uncle who shows up to Christmas every year, and you wish he wouldn’t show up, but he does.”

In 1979, Milpitas firefighters warned of the potential hazards due to the storage of toxic chemicals in various plants and factories around Milpitas, telling the Mercury: “Great Western Chemical carries ‘enough cyanide in various forms to destroy all human life in Milpitas.’”

“It was always this little town on the way to bigger things,” Mayor Richard “Rich” Tran says of his city’s modern trajectory, first as a rest-stop for travelers bouncing between Sacramento, Oakland and San Jose, to the coming of the auto industry, to the arrival of Big Tech. He insists, however, that the city has always maintained continuity.

“The neighborhoods that were there in 1954 are still here. A lot of those families are still here. The roots are deep and wide still.”

YOU OR YOUR MEMORY

A reverence for a sense of place, whether coming or going, has always been a significant aspect of Darnielle’s work, most famously expressed in the expansive “Going To” series of Mountain Goats songs (current count: over 50). However, it can also be found in the band’s early, Devil House-adjacent song “The Best Ever Death Metal Band in Denton,” as well as in the numbing dread of late-’90s Iowa of Universal Harvester, Darnielle’s second novel.

So why Milpitas? Did he simply throw a dart (that made prominent use of a pentagram) at a map to find a “gothic and baroque California suburb” to set his newest novel?

In fact, this was a homecoming of sorts. Darnielle used to live in Milpitas.

“We moved up there in probably ’73, or maybe ’74,” Darnielle tells me over the phone from Durham, N.C., following a humid morning jog.

Darnielle spent half of first grade and all of second grade in Milpitas, where he attended Burnett Elementary. A kindly teacher plays a very large, very tragic role in Devil House, but Darnielle’s memories of his school days are less horrifying and fraught than those of his characters. He singles out one teacher during his time in Milpitas in particular: Mrs. Wyatt.

“When you are a child the main function of teachers, a big function, is someone who sees you. Someone who recognizes your tendencies, what you’re into,” he says. “Mrs. Wyatt saw me real clearly. She was a gem.”

(Mrs. Wyatt, if you’re reading this, please know you made a difference in one indie-rock superstar’s life. That ain’t half bad.)

Devil House’s premise is straightforward: Gage Chandler—a reasonably successful true-crime writer—moves to Milpitas to research his next book, the grisly tale of a double murder by a group of teens in the midst of the ’80s Satanic Panic. To accomplish this, he buys the property where the murders went down: a soda shop turned theater turned newsstand turned porn store turned relatively cheap house on the market. Chandler intends to live and work in the space where the victims met their brutal deaths.

This is, of course, only the logline for book-jackets and online summaries. Darnielle’s novel slithers in confounding directions (including a head-scratching medieval chunk of text he says is “intended to slow you down”) before ultimately arriving at sensitive—if blood-spattered—conclusions. It’s not the familiar hard-boiled writer descending into madness story so much as a sideways slog toward clarity, through an unapologetically medieval lens.

As Chandler insists in the opening chapter, almost as if responding to the official summary of the novel: “It is [instead] a book about restoring ancient temples to their proper estates.”

ANCIENT TEMPLES

Darnielle’s novels are often occupied by things that don’t exactly exist anymore: play-by-mail games (Wolf in the White Van), video rental stores (Universal Harvester) and, of course, suburban ma-and-pop porno shops.

The extensive world building in Devil House is a callback to Darnielle’s own youth in Milpitas, where, early on, he was immersed in local not-quite-legends.

“I remember a girl who used to live next door to me who was one of the spreaders of what we now call urban legends. Urban legends have broader currency than what I’m talking about. These are legends that only exist on the block, and maybe only for a year or so,” he says.

The iteration of the Devil House in which readers spend the most time is a relatively benign neighborhood porn store called Adult Monster X. In the lazy interregnum between the proprietor leaving and a new buyer not yet finalized, it becomes a haven for a group of teenagers, some more wayward than others. Together, they transform Adult Monster X into their own incongruously wholesome castle.

“There’s a romance to lost things, to unrecoverable things,” Darnielle says, just after his computer crashes. “Lost and gone things have stories. There’s always a story there.”

Throughout the novel, Darnielle adroitly taps into teenage whimsy, as well as teenage wisdom. These are the sorts of kids everyone knows: a little gloomy, a little wild, often quietly decent. The book’s core struggle relates to the question of the “castle doctrine,” the law which says residents have a right to defend themselves in their own homes. As Darnielle writes in Devil House: “A person has the right, perhaps a duty, to protect himself and the stronghold from invaders. There are laws on the books about this, very old laws. They’re there for a reason.”

WHOSE CASTLE?

Gentrification, displacement and homelessness are ongoing conversations in both Devil House and Milpitas itself. According to county data, between the years 2017 and 2019, the number of residents in the city experiencing homelessness grew by 89%.

Councilmember Karina Dominguez has been an unapologetic voice for a compassionate strategy to address homelessness.

“We should not be criminalizing homelessness. If we don’t have those honest conversations, acknowledge the shame, the hurt, all the uncomfortable feelings, unfortunately we are going to continue to feed homelessness,” she says.

Dominguez is one of two members of the Milpitas City Council who doesn’t own a home. Even for its community leaders, Milpitas has become a prohibitively expensive place to live.

Darnielle was keenly aware of setting a novel about displacement and gentrification in an area infamous for its outrageous disparity of wealth. It’s no coincidence the book’s victims are in real estate and looking to make a quick buck. Even so, the murders are certainly not intended to be read as a triumphant moment.

“This is such an elementary point that it feels facile to make it, but nobody deserves to be killed,” Darnielle tells me. “Even if you’re a person who thinks some people should be killed, nobody deserves to be killed with a sword in an abandoned porn store and left there in a pool of their own blood.”

A valid point. Undeniably true. He continues: “But at the same time, some of it springs from having had 100% murderous feelings toward property developers.”

Darnielle’s current city of Durham is undergoing a similar forced transformation. In a very on-the-nose anecdote, he tells Metro he had been sharing office space with an organization devoted to helping at-risk black teenagers get their GEDs; however, due to outside forces, they were all forced from the building.

“When a town gets hot, these places get gentrified, they build castles on them. I was already writing the book, but you can believe the bloodier scenes found their range at that point.”

“I don’t want my community to hurt anymore,” Dominguez tells me. She’s talking about the entire community, even those without anywhere to call home. Dominguez and Mayor Tran have recently been very publicly at odds over the issue of homeless encampment sweeps.

“The wealth gap is so obscene,” Darnielle says. He’s talking about San Francisco, but he could easily be describing almost any city in the South Bay. “I can walk past a place that I’d have to be a multimillionaire to even bid on, and there’d be someone sleeping on the corner.”

Back when Darnielle lived there, Milpitas wasn’t an expensive place to live. And though he was tempted to make the journey back, he never returned, not even to prepare for the novel.

“I was in San Francisco right before the pandemic, looked at the freeway, thought I could totally drive there [Milpitas] and have a look. But I didn’t.”

GOING TO MILPITAS

Instead, Darnielle immersed himself in research the old-fashioned way. He ordered a big map of Milpitas and hung it on his wall, “sort of memorized it.” He took to eBay for primary and secondary documents, just as the fictional Gage Chandler does in his novel. He also studied the history of Milpitas extensively and is more than eager to share his recommended historical tomes. A few moments jar—such as a claim that there is no nearby Army Surplus store (Stevens Creek Surplus has been in San Jose since 1976)—but by and large, it’s convincing.

Darnielle is also very much aware that the book’s cover art bears a striking resemblance to another creepy South Bay staple: the Winchester Mystery House. He went there as a child, he confirms.

“The thing that left the biggest impression on me is the stairway that terminates into the wall. If you are a child and you see that, you go, wow. And they say this is to confuse the ghosts and you go, no, this is sort of bigger than that…”

But the Winchester Mystery House is San Jose’s spooky claim to fame. For Milpitas, it’s a monster movie. An incredibly aptly named monster movie: The Milpitas Monster.

Of The Milpitas Monster, Darnielle’s verdict is succinct and forceful: “A masterpiece.”

What began as a 10-minute student film about a hairy, 50-foot, garbage-eating monster snowballed (trash-balled?) into a citywide collaboration. Some $11,000 later, the film shot entirely in Milpitas would ultimately feature members of city council, police officers, firemen and high school students. The director, Robert Burrill, quipped to the Mercury News in 1976, “I had a whole town to direct.” He was only slightly exaggerating.

The Milpitas Monster premiered that May at the Serra Theater, with the early showing selling out in advance. The film, which lampooned the omnipresent stench that seemed to hover over Milpitas, is a campy triumph: an entire community banding together to be in on the joke, to revel in the noble art of laughing at one’s self before someone else does. It’s an inspiring moment of DIY can-do attitudes run amok.

Darnielle recalls watching it for the first time with great fondness.

“I’m a monster movie guy,” he explains in between regaling me with The Milpitas Monster minutia. “It was the talk of the town. Everybody was seeing it. It had an ecological message in the ’70s, which was really cool.”

All these years later, the film has a persistent staying power in his memory banks.

“In Monster Culture, this is what you’d call monster memory.” Darnielle does not elaborate on the precise definition of “monster memory” during our talk, but the phrase hits just right. “These things are really precious, tender. The way things like that got marketed was hokey, but very earnest.”

Darnielle is far from the film’s only champion.

“We love the Milpitas Monster,” Mayor Tran effuses. “We have an annual showing at our Century Theaters right around Halloween where we show the film and invite community members and kids to come watch the film. Robert Burrill, the director, is still a resident of Milpitas.”

Speaking of the stench, Milpitas still has a Community Odor Monitoring page on their website. Perhaps it’s time for the Monster to rise again.

STILL ON EDGE

If The Milpitas Monster is a nostalgic callback to a more earnest time, River’s Edge is the dreadful ghost at the feast. The 1987 film is the highly fictionalized retelling of the 1981 rape and murder of 14-year-old Marcy Conrad by classmate Anthony Broussard.

The community, by and large, did not care for the film.

“The movie should never have been made,” Terry Dehne, a friend of Conrad’s, told the Mercury in 1987, when the film premiered.

Despite the open wounds in the community, who endured the horrific moment in real time, the film has since achieved the status of a cult classic and is unlikely to ever recede as perhaps the most famous bit of Milpitas trivia. Until recently, the road where Broussard abandoned Conrad’s body had long remained a creepy detour for South Bay teens and aspiring ghost-hunters.

Mayor Tran claims those halcyon days are over.

“Marsh Road has always been this haunted place where teenagers had gone up to, to get the spook. These days, they closed off Marsh Road. It was just a big nuisance to the property owner,” he says.

Darnielle saw River’s Edge when it was released, though he had long moved on from Milpitas by the time the murder occurred. He says he found the Milpitas of the film unrecognizable, with no tangible connection to the town he spent his grade-school days and no relation to the things he remembered best about his old home: his school, his block, taking the dog out hiking somewhere nice “with cows and stuff” near (OK, this part sounds a little like the movie) a river.

“I actually haven’t seen the film,” Mayor Tran admits. “That’s something I need to do as the mayor of the city.” He does confirm that the terrible crime the film is based on is “something folks in this town still talk about every now and then.”

Councilmember Dominguez is blunter.

“There’s trauma there. A lot of it.”

WE SHALL ALL BE HEALED

That the people of Milpitas are not entirely past the city’s recent tragedy is foundational to Devil House. The protagonist’s book (and Darnielle’s own) acts almost as a sort of counterfactual sequel to the town’s famous murder and the film it spawned.

Early in the novel, Gage Chandler realizes how negatively the citizens of Milpitas reacted to the sensationalized depiction of their town in River’s Edge. He struggles with the ethics of operating in the morally ambiguous true-crime genre—especially while living among people who survived the trauma. Is it right to put them through this all over again? To make their sleepy town the center of another media firestorm? To possibly set the stage for a new unfaithful, hurtful film? To make Milpitas a byword for murder?

Up until the very end, these questions consume Devil House. In an era awash with true crime narratives, they may consume the reader as well. When I ask the (real) author if there is such a thing as ethical true crime, Darnielle, ever the artist, avoids dogma.

“My opinion is there are questions worth thinking about in all that. Like asking how ethical it is to tell stories of people whose lives were forever altered, murdered people, many of whom have survivors. Always asking what your work might mean in pockets that you weren’t already thinking about. This is good practice anywhere. It’s not just about true crime.”

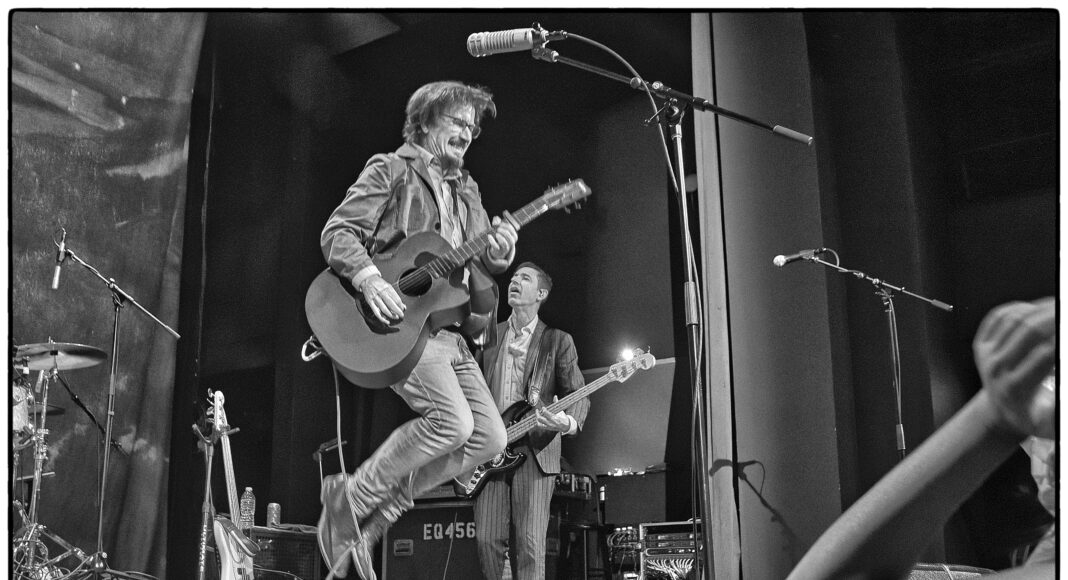

John Darnielle

Out Now

MCD Farrar, Strous & Giroux