IN VISUALIZING a sense of the livelong day of work, and in providing details of life in towns that’ll never be confused with Paris, director Stéphane Brizé has made a first-rate romance in Mademoiselle Chambon.

The film is based on a 2001 novel by the French writer Eric Holder. Without any false nationalism, this is insistently a French tale: A wife works at an industrial printer making informational pamphlets about France. Her husband and the unmarried woman who intrigues him are posed standing in front of a wall-size map of the country in a school classroom. At the end, we hear a song that epitomizes what people think of as typically French music: a tune by the one-named chanteuse Barbara (1930–97) titled “Septembre (“Quel Jolie Temps”).

Somewhere in a small city along the Toulon-Paris train line, we see a no-longer-young construction worker, Jean (Vincent Lindon), demolishing a house. We see his wife, Anne-Marie (Aure Atika), at her assembly line. Later, the two join up with their son, picnicking as he tries to puzzle out a tricky grammar question as a school assignment.

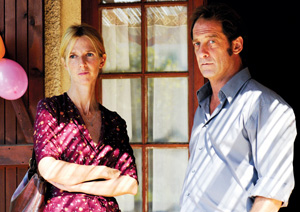

At a show-and-tell day at his son’s school, Jean is asked to explain his work to a classroom of eager kids. The camera focuses on the intense elementary school teacher, the rootless and 40ish mademoiselle Veronique Chambon (the ever-poised Sandrine Kiberlain)—and we see it, a coup de foudre: she’s fallen in love. It takes somewhat longer for Jean to get it … after Chambon hires him to repair the windows of her flat. While there, Jean notes her violin and coaxes her to play a song for him.

Without telling us outright, Brizé suggests why there’s something missing in the teacher: the loneliness that’s hollowed her out is likely connected to some dashed hopes of being a classical violinist. Music brings Jean and Veronique together across their social divide, as they sit side by side on an iron daybed.

The movie is as balanced as a good argument. Brizé pays all respects to Jean’s marriage and home. Anne-Marie is a good mom, a trim, pretty woman without pretense and with a sense of humor, seen in the evening beating her son at the card game Uno while eating Nutella out of a jar with a spoon.

Brizé contrasts this domesticity with the hard work that’s required to maintain it; the bricks laid, the swings of a sledgehammer against a wall. Like many in the construction business, Jean does it because his father did it. One of Jean’s tasks is tending to the old man, who is too beaten by age and labor to wash his own feet.

Meanwhile, he and Anne-Marie prepare for the father’s upcoming 80th birthday. The father (Jean-Marc Thibault) celebrates this anniversary by buying himself a coffin. Jean and his father linger in the tatty display room of the funeral home, apparently lined with bedspreads and bedsheets. Finally, the old man points one out, “Isn’t that the box we buried your mother in?”

Amid this suggestion of impended death, of possibilities slipping away, Brizé seems to falter at the end of the film. But he makes us feel the temptation and terror of an affair. And there’s so much tension in a final scene at the railway station that there might as well be a bomb ticking in it.

Brizé says that he made an infinitely sentimental film despite the way he hates sentiment. Mademoiselle Chambon is a tragedy too sad to weep at (though the song by Barbara may push you over the edge). The complexities and depths give this film a vigor that belies the lightweight-sounding story.

Unrated; 101 min.

Opens Friday

Camera 3, San Jose