home | metro silicon valley index | movies | current reviews | film review

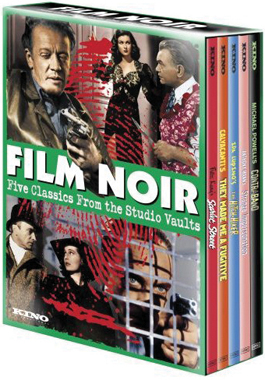

Film Noir: Five Classics From the Studio Vaults

Kino; $49.95

Stretching the definition of film noir beyond the breaking point, Kino packages a quintet of oddities (available separately but not so conveniently or inexpensively). No one doubts the credentials of Fritz Lang's marvelous Scarlet Street (1945), which reunites Edward G. Robinson, Joan Bennett and Dan Duryea from his previous film, The Woman in the Window. Robinson plays a buttoned-down wage slave and Sunday painter who gets a taste of the high lowlife when he meets a lovely tart named Kitty (Joan Bennett, who makes a memorable entrance in a clear plastic raincoat). Turns out Kitty and her snarky, stylin' pimp (Dan Duryea in a straw boater and bow tie prepping for his role as Slim Dundee in Criss Cross) are conniving on Robinson's imagined fame and fortune as an artist. The film, in true noir fashion, plows inexorably ahead to an unusually down ending. This disc features an excellent new transfer from a Library of Congress print and looks much better than any of the other copies I've seen. One the other hand, what is one to make of Contraband (1940), a bit of British wartime propaganda that predates the noir cycle? It stars Conrad Veidt (a German actor who often played stereotypical Nazis, most famously as Maj. Strasser in Casablanca) as a Danish tanker captain who helps a perky English spy (Valerie Hobson) foil some German operatives in London. The action is interrupted by so much comic relief (who knew that the Danes were such cutups?) that keeping track of the plot isn't worth the effort. Nothing here even hints at the better work of the team of director Michael Powell and writer Emeric Pressburger: Black Narcissus and The Red Shoes. Perhaps the patriotic message is meant to set the stage for the postwar malaise of They Made Me a Fugitive (1947), in which Trevor Howard plays a disaffected RAF vet who joins a gang of black marketeers headed by Narcy (short for Narcissus, and played with brio by Griffith Jones). Jailed for a murder he did not commit, Howard escapes from prison and tracks down Narcy, who framed him. His encounters along the way (including a bored housewife who wants him to murder her husband) paint a dyspeptic portrait of England's slow recovery from the war. The action sometimes falters (Howard takes out some heavies with a milk bottle), but there is a great rooftop battle framed by giant letters spelling out RIP, and some weird crackling dialogue ("This is the last time Morgan runs his fingers through my permanent wave"; "It's like taking ju-jus from a blind baby.") The film offers interesting parallels to some of the noirs about lost and psychologically damaged war vets made in America, like The Blue Dahlia and Somewhere in the Night. Ida Lupino's The Hitch-Hiker (1953) is based, it claims, on a real story —"For the facts are actual." Schlubby pals Edmond O'Brien and Frank Lovejoy are carjacked on a fishing trip in Mexico by William (Hamilton Berger on Perry Mason) Talman's serial killer. Lupino's direction is stripped down: a man's feet approaching a car, the door opening, a scream, a gun shot, and we're off. The box set wraps with Strange Impersonation (1946), an early effort by noir expert Anthony Mann (T-Man, Raw Deal, Railroaded). Brenda Marshall plays Nora Goodrich, a scientist who wakes up disfigured after experimenting on herself (!). The premise goes careering off the rails as her lab assistant vamps her boyfriend, and a blackmailer puts the pinch on Nora. When the blackmailer turns up dead, Nora takes her identity, travels to L.A. for a year's worth of plastic surgery (at no charge, apparently) and then returns to exact her revenge. This somewhat crazed and occasionally risible film could be called a noir, but it really belongs in that weird subgenre of movies about plastic surgery, where Stolen Face, A Woman's Face and Dark Passage dwell. (Michael S. Gant)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|