home | metro silicon valley index | music & nightlife | artist review

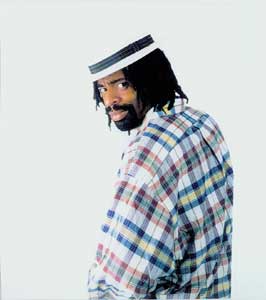

Crestside Clown: Not fitting the mold was one of Mac Dre's enduring qualities.

Feeling Himself

Wanda Salvatto ponders the legacy left by her son, Mac Dre

By Gabe Meline

LANGTON ALLEY in San Francisco is a long, narrow one-way street, not unlike any other alley in the city's south of Market Street area. Its gutters are lined with crumpled trash, its sidewalk spotted with urine. Between the towering walls lies a drab sensation of facelessness—you're no longer walking in any distinct city—until the alley's end, next to a freeway onramp, where beaconing from above is what has quickly become the most beloved graffiti street mural in the city. This one has been up for months, and it stands untouched. Two airbrushed portraits dance across the walls, the words "REST IN PEACE" standing boldly atop the memorial.

"Nobody's gonna mess with this," says a young girl nearby, one of many who have come from out of town to visit this alley. She takes a few pictures and adds, "You don't touch Mac Dre."

By now, the story of Mac Dre's career—and especially its fateful end—constitutes a tale of young street life, hard jail time and eventual redemption. But from reading stories about Mac Dre in the papers, you'd think that his sole appeal lies in his tough life of crime; the media has reported extensively on his alleged gang ties and has linked three murders to his in the last year.

Whether these connections can be proven or not is a question that ignores the very heart of Mac Dre's appeal and leaves unexplored the nuances of his life and artistry, which offer an important lesson in staying true to oneself and succeeding because of it. Mac Dre came out of this world on top with legions of fans who feel a special, personal connection to the man called the "Crestside Clown." I recently spoke extensively with Mac Dre's mother about his life and legacy, and what emerged was a portrait of a passionate, fun-loving, good-natured kid who never fully got the chance to grow up.

Mac Dre was born Andre Hicks in Oakland on July 5, 1970. Speaking from her Vallejo home, just after the one-year anniversary of her son's death, Hicks' mother, Wanda Salvatto, remembers noticing from an early age that he was a rampant individualist.

"The thing about Andre as a child," she says, "was that he was always very, very outgoing and outspoken. He had a mind of his own early on and followed his own direction." His parents tried to get him involved in sports, but Salvatto says he took more interest in talking to other kids than in playing games with them. "He was interested in all kinds of people," she says, "and in the differences in people. It fascinated him to meet white kids over in Marin, black kids in Country Club Crest, Mexican kids ... y'know, the people thing interested him. He opened up to everybody."

It wasn't until the family moved to the Country Club Crest neighborhood, known as Crestside or "the Crest," that a clear picture of his future started to take shape. Hicks and his friends had begun dragging home large rolls of linoleum for breakdancing in the garage. He also started asking for keyboards, Salvatto recalls, and early in junior high he started to pick up the microphone and started rapping and writing lyrics himself in the seventh or eighth grade.

Before too long, rap music had become a coast-to-coast phenomenon, and Vallejo's own underground began bubbling. One of Vallejo's early pioneers, Michael "The Mac" Robinson, released the groundbreaking album The Game Is Thick in 1988; its influence would be felt throughout Vallejo in all the years to come. The young 18-year-old prot´gé, Andre Hicks, adopted the name "Mac" in honor of his mentor, and Mac Dre was born.

After three acclaimed albums, including his sensational debut, Young Black Brotha, Mac Dre found his music the focus of an unwanted kind of attention. A string of robberies had been spotlighted on the television show Unsolved Mysteries, and police were pressured to find the members of Vallejo's Romper Room gang, widely believed to be the perpetrators. Dre had been picked up in Fresno with some friends, and a court case was trying Dre on conspiracy to commit bank robbery. Strapped for evidence, the prosecuting lawyers relied upon the lyrics from Young Black Brotha.

Salvatto stayed in Fresno during the hearings and was crushed when the court accepted his lyrics "as gospel." Her son faced a five-year prison sentence at Lompoc Federal Penitentiary. While in jail, Dre's spirit was unbroken, as was his fan base. He continued writing and occasionally performed for other inmates through special events on the prison's stage. Dre also secretly recorded an album, Back N Da Hood, live over the jail's telephone.

Mac Dre's first album post-jail was Stupid Doo Doo Dumb, the cover of which depicts him sitting on the toilet with his pants down, reading a magazine, surrounded by voluptuous girls in bikinis. This image was to set the tone for the rest of his career: still in the game but with an extraordinarily bizarre sense of what was cool.

Two key elements began to emerge: (1) he was never afraid to loosen up, to have fun and be himself, and (2) he never fulfilled the public's appetite for predictable clichés. His vocabulary was increasingly riddled with mysterious inventions and esoteric meanings, and he started giving himself nicknames, eventually adopting different personas altogether for albums like Thizzelle Washington and Ronald Dregan.

One of Dre's favorite sayings was "It's not what you say, it's how you say it," and it was strongly reflected in his new lyrical flow. Variety became the spice of his rapping, as his songs were alternately carried in whispers, British accents, animal sounds and other intentionally innocuous inflections. Even at its most straightforward, a pervading jovialityéthe very antithesis of thugéhad crept into his vocal delivery. He was working harder than ever; Dre dismissed pimping and other rap conventions. As he rapped in "Fire," "They hate to see a player employ hisself/ They hate to see a player enjoy hisself."

His flamboyance reached new heights with songs like "Get Stupid" ("You can do it, it ain't that hard/ Baby, get dumb/ Act like a retard") or the landmark "Thizzle Dance," a paean to the dance-song craze of the 1950s and a showcase for Dre to act nuttier than ever. As instructed by the lyrics, the dance involves contorting your face like you "smell some piss" and then dipping, sliding, flapping your arms and popping your collar to the robotic, animated beat.

Dre could have easily been written off by his fans and street-hardened peers as too outlandish or even disgraceful. Instead, his creative antics were like raw meat to a rap community of lions hungry for something new, and his album sales skyrocketed. "People encouraged him," remarks Salvatto. "It was refreshing; it was different. A lot of people commented that they didn't know he was so funny."

Around this time, Dre bought a house high in the hills of Sausalito, about as far from the Crest as is possible. "Andre was on the verge of really changing his lifestyle," remarks Salvatto. "He really wanted to enjoy the benefits of his music. It had gotten to the point where he was beginning to be really successful and he could afford to live anywhere he wanted." Dre's move-in date was Nov. 1, 2004.

It was a routine trip to Kansas City, a place Mac Dre had visited and performed in many times before. This time, though, something was amiss, and a misunderstanding with a local promoter had led to a canceled appearance. Around 4:30am on Nov. 1, Dre was in a van driving down Kansas City's Highway 71 when a car with no license plates pulled alongside the van and an occupant opened fire.

The van crossed over two oncoming lanes of freeway and went down into a deep ravine, throwing Dre from the van. The driver, Dre's longtime friend Dubee, crawled back up the ravine and went to a convenience store for help. When ambulances arrived, Andre Hicks was pronounced dead from gunshot wounds.

One year after that night in Kansas City, large crowds gathered at Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland and in Vallejo's Crestside neighborhood to commemorate the life of Mac Dre, but his mother didn't want to be in town. Instead, she spent the day driving down the California coast on Highway 1. "I had to get away," she explains. "Andre's death is very, very personal to me, so I tend to deal with it in a quiet way."

Yet being in charge of the artist's estate is anything but quiet; it is a balance of the checkbook as well as the heart.

"I've spent the last year just trying to get a handle on Andre's 20 albums," says Salvatto, "and that in itself has kept me busy in the last year and will probably keep me busy for the year to come. Just getting it all under control ... the copyrights, finding out where it's being distributed and who's paying and who's not."

Then there is the problem of Treal TV #2, the long-awaited follow-up DVD to Treal TV. Despite overwhelming demand, delays have plagued its release for over a year, first from other rappers who appear in the footage and who want to get paid. Now, the delay is coming from the final editing room, and Salvatto is taking a more active interest in how Dre is presented in the video.

"He wouldn't like me saying this," she admits, "and of course this is coming from a mother, but he was having a good time, and there was a lot of stuff that happened—the fights, the drugs and stuff like that—that I wouldn't necessarily approve of."

Naturally, Salvatto had no control over her son's activity when the footage was filmed, "but I mean, what are you going to tell a thirtysomething-year-old man," she asks, "that no, you can't do this, you can't be filmed doing that? That was never Andre, even as a child, for me to be able to do that."

"But now ... ," she stops to consider the delicate position she is in, of editing her own son's life, "I want to be careful about the way Andre is projected because I think he had become another person, and I think he would have been more careful about the way he would be projected now as well."

All of this is hard work, and for a grieving mother it can be emotionally numbing. Salvatto realizes that there is nothing she can do about what happened in Kansas City, or about the fact that his murder is still unsolved. "I think that God will take care of whoever did it. There are a lot of parents whose children have died, and their murders or deaths are unsolved," she says, knowing that she's not alone. "Some parents don't even know where their dead children are. At least I got to bring Andre home and bury him, and I know where he is now, and I know where to go visit him."

It's been over a year and Mac Dre's impact is still felt, his death still mourned. His lessons of taking pride in your own self-confidence and living happily by your own rules still resonate from the ghettos to the suburbs, and meanwhile, there are hundreds of hopeful rappers from every city in the Bay Area aspiring in the ripples of his wake for a piece of the pie that Mac Dre virtually wrote the recipe for. But Mac Dre's career is a sealed legacy. It is his and his alone. It's like the girl in the alley says. You just don't touch Mac Dre.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.