home | metro silicon valley index | movies | current reviews | film review

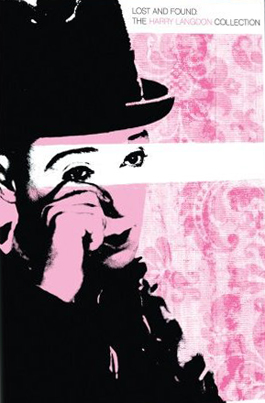

Harry Langdon: Lost and Found

Four discs; All Day Entertainment/Facets Video; $39.95

With a slow blink, the pale, toddler-faced comedian Harry Langdon could express anything from mild reproach to major shock. Childish, wizened and badly dressed, this "white mouse," as historian Kevin Brownlow called him, stumbled through life's minefield. Sex lured him and demolished him; women ate him alive and spat him out. Onscreen, Langdon (1884–1944) was a Taoist comedian, carried along by whatever flow of power came his way. "I'm an animated suit of clothes," he once said, and throughout his silent work he took the path of least resistance.

All Day Entertainment/Facets Video's lovingly assembled four-disc set Harry Langdon: Lost and Found follows the formative years of the one of the most major, yet least known, of silent comics. Years later, after Langdon was a second banana in Poverty Row shorts, producer Mack Sennett described Langdon as "my most important discovery"—and this was from the person who'd promoted Charlie Chaplin. There's a lot to be learned from this collection. One lesson is that no matter how much we lionize the best silent comedians—Chaplin, Keaton and Lloyd—the 20-year reign of silent comedy was a symbiotic free-for-all of styles, with borrowing and theft on all corners. Langdon dressed like Chaplin in too-tight or too-loose thrift-shop finery, though the mauled felt hat was his own personal signature. Like Harold Lloyd he could be a wet-behind-the-ears go-getter. Like Buster Keaton, he faced disaster with a fixed look of resignation. Maybe Langdon might scratch a mild itch somewhere on his head as he waited for the wrecking ball to fall. Or perhaps he'd give up his most lethal reaction shot: a myopic twitch of his eyelids. Langdon haters, and there are plenty of them, complain that Langdon never does anything. "It takes him an hour to get started," Frank Capra recalled complaining to Mack Sennett.

Critic James Agee, the first partisan to revive Langdon's reputation, put it best: Lloyd, Chaplin and Keaton were more like each other than Langdon was like the rest of them. And Langdon, a comedian's comedian—was a great minimalist who paved the way for generations of anti-comedians to come: Andy Kaufman, Steve Martin and especially Pee-wee Herman.

This collection includes Langdon in 16 two-reel Sennett comedies made 1924–26, and two slightly longer feature films, Soldier Man and His First Flame. The former, a burlesque of The Prisoner of Zenda with Harry in a dual role as a lost soldier and King Strudel XIII of Bomania, is presented in a 31-minute version of a four-reel original. (A silent film reel is around 12 minutes long; sound reels are shorter.) The release of this film by Sennett, after Langdon had gone to First National studios, contributed to the late 1920s glut of Langdon films—and that glut is perhaps one reason for Langdon's demise as a star.

But this retrospective of Langdon at Sennett's laugh factory shows how he rose to the top. His first exhibited film with Sennett has Harry as a debonair letch in the 1924 two-reeler Picking Peaches. Smile Please, a scintillatingly gauche piece of Sennettry (complete with performing goat and skunk), could have starred any boisterous comedian and worked just as well.

And yet just six months later, in the brilliant 19-minute short All Night Long, Langdon was recognizably himself. He plays a pale boob who always lucks out, in a finely structured tale alternating between a World War I battlefield and a chance meeting in a deserted theater. Here, Langdon was adept in what Capra called "the principle of the brick." It's a theory that has much to disprove it, as we can see—Langdon threw his share of projectiles. But Capra's idea was that Langdon might be the agent of malign fate (a brick hitting a bully in the head), but he must never toss the brick himself.

All Night Long starred Langdon's regular partner, Vernon Dent—a hulking brute with a head like a cannonball—who usually got brickstruck. (Dent later used his heavyweight grouching skills in many a Three Stooges short; I remember the Ibsenish, brooding quality he brought to the role of Mr. Panther, head of the Panther Brewing Company, in the Stooges short Beer Barrel Polecats.) Dent and Langdon were a top-drawer comedy team, closer to Penn and Teller than Laurel and Hardy. Saying that, it should be noted that there was much symbiosis between Stan Laurel and Langdon—Laurel borrowed some of Langdon's mannerisms and later hired Langdon as a writer on Laurel and Hardy's Hal Roach films.

The better of the two longer feature films in the collection is 1927's His First Flame, the story of a rich simp who is persuaded away from girls by his bitter fireman uncle (Dent). It's a series of short, violent hideo-comic tales about the war between men and women; the most dire incident has a wife forcing two men to eat at her dinner table at knife point.

His First Flame shows significant technical improvement over Sennett films made just two years before. The focus of the camera is deep, and the build-ups are deliriously slow. The scenes of a drowsy 1920s Los Angeles are irreplaceable; and there's enough clarity in the foreground to see something as small as a pair of teardrops on a floor. This collection reveals Langdon evolving before the camera in record time. After this feature, Langdon left for First National and a short period of world-class fame.

So what happened? Sound, of course. Langdon talked like a squeakier Lou Costello. A funny voice, but it wasn't the funny voice that an audience might have though he had. Langdon was older than the other three famous silent clowns and thus hit harder by the years to come. Capra, always glad to appropriate credit, told everyone who would listen that Langdon was a talent Capra had shepherded. In Capra's version, Langdon went off the rails after he started to believe his own reviews. It was the saddest show-biz story in Capra's recollection, and that's the way it was repeated in his often truth-impaired autobiography The Name Above the Title.

One of the commentators in Lost and Found, a 74-minute documentary in this set, suggests that Langdon's second wife, Helen Watson, may have been the one who encouraged Harry into bad career decisions. Certainly Watson bled Harry for alimony whenever the aging comedian got ahead. But repeatedly—conclusively—this collection argues that Capra may have been a valued contributor to Langdon's comic art, but he wasn't the man who shaped Langdon's fog-bound persona.

Moreover, there's much proof that Langdon still kept his talent post-Capra. In addition to commentary tracks and extras, there are two 1933 shorts for the bare-budget Educational Films, which also hired Keaton after Buster's career crash. In 1933's Knight Duty, Langdon works on some prime gags in a deserted wax museum; he and Dent (as a hulking policeman) handsomely survive stodgy direction and a female lead who genuinely belonged in a waxworks.

Love, Honor and Obey (The Law) is a B.F. Goodrich–produced promotional short from 1935 co-starring Langdon with snazzy, fox-faced comic Monte Collins. Despite its disagreeable title, it qualifies as the funniest driver-training film ever made. Langdon, first drunk, then hung-over, is required not to get a single traffic ticket since he's getting married to the daughter of the chief of police. The shorts are scored with newly recorded soundtracks by the Snark Ensemble and the Redwine Jazz Band. Clarinetist Ben Redwine is involved in both, and he's perhaps the best interpreter of nontrad silent-comedy scoring since the Club Foot Orchestra. While he uses the traditional ragtime tempos, he gets into more rarefied modes that range from klezmer and Brubeck.

The collection leaves you wanting more. Langdon worked in Columbia two-reelers during the '30s and '40s in the same comedy shorts division where the Three Stooges were flourishing. We don't get to see any of it here, except in stills. In the documentary, there are no excerpts from Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, Long Pants or Langdon's most universally appealing film, The Strong Man.

Langdon's Heart Trouble doesn't seem to exist anymore—except in the sense that its press kit is included here as a CD-ROM. And what about Three's a Crowd—a kind of situation tragedy in which Langdon is billed as "The Odd Fellow"? It, too, is praised during interviews but can't be shown. Once again, copyright extensions do their part to keep films hidden. (Thanks, Sonny Bono, wherever you are.) Still, as labor of love and robustly argued defense of the reputation of the least-known of the Big Four, Harry Langdon: Lost and Found is the kind of silent-film rediscovery that you wouldn't have thought was possible at this late a date. (Richard von Busack)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|