home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | visual arts | review

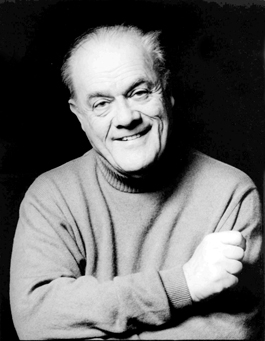

GENIAL SKEPTIC: Musicologist Charles Rosen worries that we are fetishizing past performance styles.

Listening To the Past

A conference on recording history unearths rare samples of 19th-century sounds, from Russian wax cylinders to the pianola

By Richard von Busack

WE ARE accustomed to the idea that all music is available at all times, at least to anyone with a computer. But depending on recordings to perceive the original intentions of a composer is sometimes as unreliable as taking the events in a movie for actual history. This weekend (Jan. 14–18), a Stanford symposium called "Reactions to the Record II" analyzes the gap between intention and performance in eight concerts and several seminars and lectures. Other events include an improvisational piano contest by Genadi Zagor and William Cheng.

Among the headliners is pianist and musicologist Charles Rosen, a contributor to the New York Review of Books. In his review of the six-volume Oxford History of Western Music, Rosen put it plainly: "The printed text is invariable, while two performances are never exactly alike." Notation has allowed Western music its peculiar complexity, but the progress of music is never as A to B to C as it seems. And Rosen uses the strong word "fetish" to describe the search for old methods of performance.

Conference organizer Kumaran Arul of Stanford claims that Rosen has been brought in "as a critic—a respectful critic—of what we're trying to do. Rosen's concern is excessive historical simplification: the problem that even if we do know what a great composer played like, we wouldn't want to do it like that.

"Similarly, there are others who take quite a different view," Arul continues, "people who are actually trying to play the past. We can never really know in some degree what the great composers of the 19th century played like. There is a movement to play Bach and baroque music on old instruments, like the Philharmonia Baroque here in the Bay Area. But there's a lot of controversy there, and accusations of self-consciousness. Baroque music has no recording, but there are some 19th-century recordings. We have some good evidence of how Joseph Joachim played, so why not try it?"

Pianist Arul will accompany David Milsom, the author of Nineteenth Century Violin Practice, on a performance of Brahms' Violin Sonata no. 2 in A Major (Jan. 15 at 8opm). Milson will also lecture that day (at 10am) about his method of resurrecting Joachim's style of playing.

Some consider player pianos as a mechanical novelty. But some paper rolls for these pianos are now highly prized. Take the George Gershwin recordings from piano roles rereleased on record a few decades ago. There's a surprising jazz-age raucousness of attack that decades worth of cafe pianists would make gentler in decades to come. "We've had a paper on Gershwin's old recording," Arul says. "The author claimed that we've completely gone away from Gershwin's style, but actually he really likes that. It could be that either composers aren't the best interpreters, or else the times have changed, and we can't appreciate the older styles."

In any case, there's a difference between the penny-arcade piano and the pianola produced by the Aeolian Company. Arul comments, "Pianolas are expressive devices." While the common player piano—a "reproducing piano"—results in the same performance every time, a pianola allows human control of the speed and pedaling. Expert Rex Lawson will demonstrate the pianola's abilities on Sunday at 8pm.

Hindemith and Stravinsky both composed for the instrument. Edward Grieg's own version of op. 43, no. 1, The Butterfly, can be found on the pianola.org website, in a lambent, impressionistic performance that sounds closer to Debussy than to Nordic thunder.

According to Arul, "one of the reasons piano rolls matter is that 1905 piano rolls are of a much longer length than we could get out of the acoustic disc. We have a better presumption of intention from actually hearing a performer play, but there's some unique benefits of the piano rolls. We can see all the notes. We can't hear all the notes on a old acoustic recording. However, most of those pianos are in poor quality today. ... So they have been disregarded by musicologists and scholars."

REACTIONS TO THE RECORD II takes place Jan. 14–18 at Braun Music Center, Stanford University. See http://stanfordmusicsymposium.stanford.edu, or call 650.465.7321.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|