home | metro silicon valley index | features | silicon valley | feature story

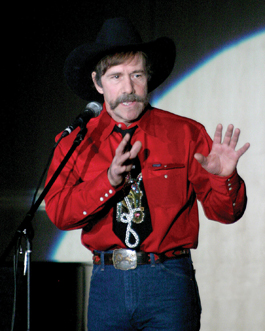

Photograph by Felipe Buitrago

YODELING JAZZ CATS: Local musicians Lee Ray, Tim Volpicella, Gordon Stevens and Scott Sorkin went into a San Jose studio with the poet Paul Zarzyski and made a mighty unusual cowboy poetry CD.

Wild in Willow Glen

Cowboy poetry meets free jazz in a fancy studio on Lincoln Avenue

By Gary Singh

ON A LAZY CHRISTMAS EVE, Gordon Stevens guides me through the corridors of the Music & Entertainment Business Center, a masterpiece of lightweight '50s kitsch architecture at 1202 Lincoln Ave. in Willow Glen. His family's company, Stevens Music, operated at this address from 1961 until 1984, and nowadays the edifice functions as a hodgepodge co-op of several businesses including Stevens Violin Shop, Willow Music School and LifeForceJazz Records. It also houses Open Path Music, Gordon's state-of-the-art recording and production studio, where several heavyweights of the Bay Area jazz community have laid down tracks.

As we navigate the corridors of the building—where I meekly recall first taking keyboard lessons in 1979— we discuss one of Gordon's recent and most profound collaborators, Paul Zarzyski, the "Polish hobo-rodeo-poet" of the American West, who cut two spoken-word CDs right here at Open Path, and who will perform at the 25th Annual Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, Nev., later this month.

Zarzyski, born in Wisconsin, went native after moving to Montana in 1973. He holds a master of fine arts degree in creative writing from the University of Montana, where he studied with the legendary poet Richard Hugo. After knocking around the freewheeling college town of Missoula for a decade or so, running with such legitimate literary luminaries as William Kittredge, Jim Crumley and Rick DiMarinis, Zarzyski left and moved to a ranch near Great Falls, where he still lives and raises horses.

Although he has cranked out traditional bronco-riding, range-related, haystack verse for 30-plus years since, Zarzyski also continues to obliterate the boundaries of cowboy poetry, reshaping the form with profound free-stylings on everything from Steven Hawking to marijuana to the Holocaust. He won the 2005 Montana Governor's Arts Award for Literature.

A dude who knows the intricacies of the rodeo chute as well as the trials and tribulations of the academy, he may be the only MFA-packin' artiste to regularly attend the Elko hoedown.

Stevens first collided with Zarzyski at a previous Elko gathering and the two eventually developed a creative, almost cosmic rapport. As a result, Zarzyski headed on down to San Jose and recorded the CDs Rock 'n' Rowel and the more progressive Collisions of Reckless Love.

In a series of recording sessions Zarzyski describes as "mystical" and "magical" in the way the collaborators all fed off each other, he recited the poems while Stevens and his comrades turned out spontaneous music that miraculously dovetailed with the poetry in ways they hadn't planned. Weepy piano accompaniment emerged for some poems, while multi-instrumental conversations escorted others.

"It was a synchronicity that doesn't happen often," Zarzyski said. "But when it does, it really makes you understand the infiniteness of the creative process."

Stevens agreed. "I'd say 80 percent of all that music was ad-libbed," he recalled "[Paul] sent us the poems and we looked 'em over. We didn't write music for them—we took thematics and stuff that we all contributed—my partners, the four of us—in the studio. They all liked it, they felt his power, and he came into the studio and it was one of the most amazing fucking experiences of my life, the way it just fell together."

Many poets and musicians weave similar stories about meeting future collaborators at the Elko gathering, so on a recent visit to the Silver State during the off-season, I decided to get the whole nine yards.

Maps and Legends

Located in the northeastern corner of Nevada, along Interstate 80, Elko is 295 miles from Reno and 230 miles from Salt Lake City. By any definition, it is in the middle of nowhere. One can arrive via air from Salt Lake, but the authentic Elko experience must include driving three hours through the sagebrush sea of northern Nevada to get there.

The Western Folklife Center, the regional nonprofit that organizes the gathering, currently exists in downtown Elko's historic Pioneer Building. Formerly a hotel, a flophouse and a strip joint, the structure dates back to 1913. George Gund III, former owner of the San Jose Sharks and a benefactor of the cowboy poetry gathering since its inception, donated funds for the building's purchase in 1991, and the facility now includes an art gallery, a 300-seat theater, an authentic Old West saloon and a gift shop. (The saloon still features the original 40-foot mahogany and cherry wood bar that used to sit out on the street in front of the building nearly a century ago.)

Upon crossing the threshold of the building, I seriously consider going native. The bar is to the right, the gift shop and gallery are to the left, while framed posters from the first 24 gatherings cover the walls. I plop myself down into one of the couches near the fireplace while the center's executive director, Charlie Seemann, as well as education and outreach coordinator Christina Barr school me on the layman's history of cowboy poetry and song.

Photograph by Molly Morrow

RHYME WRANGLER: Paul Zarzyski may be the only cowboy poet with an MFA degree.

"It's rooted in all the traditional cultures of the West," Seemann says. "Basque, Latino, Tongans, Samoan, etc. And also in Old English balladry. ... And it's typical of occupational poetry when people are isolated—miners, sailors, fishermen's poetry—things like that."

Twenty-five years ago, a few dozen cowboys gathered in Elko during the dead of winter to swap drinks, lies and poetry. Nowadays, the weeklong shebang features nearly 100 performances, lectures, impromptu jams, ranch tours and workshops on everything from rope-braiding to sausage-making. The gathering has spawned more than 250 smaller festivals all throughout the country.

"The first one was intended to be a one-time event," Seemann recalls. "In putting it together, the idea was that it'd be kind of a nice thing to honor these older guys who still knew this stuff and got to meet each other. They all had too much fun, the press loved it, and they said, 'Let's do it again next year.' Frankly, I think everybody's a little surprised at the longevity of it and the fact that it just seems to keep getting a little bigger."

This year will be Zarzyski's 23rd consecutive appearance at the gathering. He says the musical relationship forged between Gordon Stevens and him is indicative of the spontaneous, unexpected friendships Elko is known for creating.

"You go to Elko and shit happens every year," he said. "There are close encounters of the umpteenth kind between people who would otherwise have never met on this planet—thousands of friendships and acquaintanceships and artistic collaborations that would have never existed."

The Original Dudes

At a private banquet in the Western Folklife Center, Baxter Black—the best- known, most published and easily the most hysterical cowboy poet of them all, the one who first brought the genre to a mainstream city slicker audience, enlightened the crowd with a cockamamie explanation of how it began.

"We owe a great deal to John Travolta and Mickey Gilley," he quipped. "Somewhere in the late '70s they invented the urban cowboy. Then people in orange leisure suits started wearing boots and these huge ugly hats that looked like they were made out of oatmeal."

Soon thereafter, the story goes, Black and others began to grace the stage of The Tonight Show, bringing the cowboy poet's sensibility to the rest of America.

"The oxymoron of the words 'cowboy' and 'poet' just did something," Black explained.

Since then, the festival has morphed over the years into a more commonplace gig, appealing not just to folks who work the ranches, but to anyone interested in preserving the lifestyle and folklore of the American West.

"The first two or three years, it was pretty much a hard-core ranching audience," Seemann recalled. "The aunts and uncles and cousins would come, and the local buckaroos and cowboys. Then the media got a hold of it—The Today show and The Johnny Carson Show—and other people started getting interested as well.

"I would say, over the years, that the percentage of the audience interested in the genre and interested in Western culture are people who live in the West but aren't from ranching backgrounds. That percentage has increased significantly, so that's actually now probably a preponderance of the audience. There's still a lot of ranching people and working cowboys that come to it, but they're certainly not the majority of the audience anymore."

Zarzyski concurs, adding that the Elko crowds have expanded across the board. A wide variety of poetic forms are met with open arms.

"They love it all," he says. "It's like tapas. They want a little bit of everything. They want a little taste of it all. They want the old traditional poems back from the 1800s and early 1900s, they want the contemporary poems in the old forms, they want meter and rhyme, they want the new free verse work, they want the poems that are about horses and cattle and double-rigged saddles, and they're very willing to move from that. I've never stood before a more open-minded audience."

El Rancho Willow Glen

The building at 1202 Lincoln Ave. in San Jose goes back decades. Gordon's father Tom Stevens originally ran a music business in a small storefront down the street before moving into this structure in 1961, when it became Stevens Music. Gordon himself was born in 1936, attended Markham Junior High School and then Willow Glen High before playing strings for the San Jose Symphony.

After a stint in the Air Force, he worked at the store throughout the '60s, manning the counter and repairing instruments. Over time, Stevens Music soon expanded to five stores, including satellite shops in Concord, Sunnyvale and Milpitas, and eventually becoming the sole Bay Area distributor for Yamaha products, especially pianos.

"My dad was really interested in keyboards, mostly," Gordon Stevens remembered. "Because that was the big bucks, you know. And my job, I was the manager of all the rest of it—all the guitars and trumpets and saxophones, because we had all the major franchises. We had everything."

As the '60s drew to a close, Gordon left the store for a few years when Skip Spence asked him to join the psychedelic rock band Moby Grape. When that situation caved in, Stevens returned to the store and launched Stevens Violin Shop upstairs, where it exists to this day. Throughout the '70s, Stevens Music continued to operate, although under some stiff competition from emerging specialty shops like Guitar Center, Guitar Showcase and Bob Berry Pianos. As a result, they backed off from functioning as an all-purpose music store and continued to concentrate their operation around the remaining Yamaha franchise.

By 1984, however, the writing was on the wall and Tom Stevens decided to retire. The family sold off the corporation and closed down all the stores, but kept the building at 1202 Lincoln, along with the violin shop, which was booming. Another store, Reik's Music, moved in downstairs, but eventually folded. Then Gordon reorchestrated the building as a co-op with separate tenants and christened it the Music & Entertainment Business Center. Open Path Music, his state-of-the-art recording and production studio, is located at the far back of the street-level corridor—seemingly hidden from the rest of the world driving by outside on Lincoln Avenue.

After Stevens met Zarzyski at the Elko gathering, the two exchanged correspondence for a year and then joined Ramblin' Jack Elliott, Tom Russell and others on the 2005 Roots on the Rails Cowboy Train, a trip from Vancouver to Toronto, where folks pay $2,000 to drink and exchange the songs, poetry and philosophy of the Old West—all while traveling on a train for four days. Their friendship then grew and Zarzyski descended upon San Jose to record the two CDs at Open Path.

With a Polish hobo-rodeo-poet from Montana in a studio full of veteran San Jose jazz musicians, one would expect either a supreme clash of civilizations or a cosmic meeting of the creative minds. According to Zarzyski, it was the latter.

"So I fly into San Jose—and a recording studio is not foreign to me—but they wanted to do something different," he said. "They didn't want to bring the country-western steel-guitar sound to these poems." Instead, Stevens, along with his partners, came up with more varied accompaniment, sometimes tonal, other times more abstract and cosmic.

"The Day the War Began" features Zarzyski reading his poem against spontaneous piano lamentations by Denny Berthiamune. Another poem, "Last Rematch," finds a washed-up boxer contemplating his scenario in a cellar on Christmas Eve, while a smoky, slithery sax-and-percussion accompaniment eggs him on. And for "Luck of the Draw," the opening track on Collisions of Reckless Love, the musicians, almost telepathically, sync with Zarzyski—to the point where the music sounds like it was written down and arranged as a soundtrack beforehand—but it wasn't.

Zarzyski, who says he knows nothing about music, somehow found the right tempo and rhythm that coordinated with what the musicians were doing.

"It's almost like he was singing to us," said Stevens.

Throughout the rest of the sessions, similar exchanges took place, leaving all parties involved blown away by a new musical rapport sprouting from the chaos—one where the emergent whole was greater than the sum of its parts.

To Zarzyski, it's significant that the entire cosmic relationship originated in Elko—in the middle of nowhere.

"Through a lot of give and take—especially give—within days, we began to trust one another with our heart and our art," Zarzyski says. "And it's an amazing scenario and phenomenon, that's connected to some kind of power—don't ask me where it comes from—a power that just developed in this silly little mining town in Nevada, for chrissake."

Cozmic Cowpokes

Looking back on the two CDs recorded on Lincoln Avenue, Zarzyski uses the metaphor of a coloring book when connecting the dots between himself and Gordon Stevens, between Elko and Montana and San Jose. He says the connections were like filling in the smaller shapes, with the bigger picture eventually emerging.

"And after all that, you find out that we're not as different as many people would want us to believe," he says. "We're very much connected at the heart. And that's so important to my joyousness on this earth, in believing that. I mean, I never thought I'd wind up in a recording studio in San Jose, but why should I have doubted it?"

In the end, I asked Stevens what it was like, for this project with Zarzyski to cosmically materialize the way it did. For all those dots to connect in that studio, buried at the back of that corridor, in that building at 1202 Lincoln—all while the rest of San Jose drives by outside, not even aware of what's going on inside.

"I think about that a lot," he said. "The world just keeps driving by."

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|