home | metro silicon valley index | music & nightlife | band review

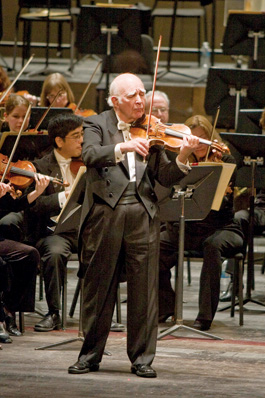

Photograph by Robert Shomler

Doulbe Threat: Guest artist Joseph Silverstein conducted and played the violen for Symphony Silicon Valley over the weekend.

Master's Touch

Scott MacClelland

JOE SILVERSTEIN still has it, and in spades. The diminutive 75-year-old violinist with sad, bushy white eyebrows gets—and deserves—bravos, and outshines many a youthful podium firebrand with nothing more in his hand than a conductor's stick. With Symphony Silicon Valley last Sunday, he proved it again, on both counts, playing Vaughan Williams' Lark Ascending and Mozart's Fifth Violin Concerto and conducting a stylish and insightful account of Elgar's Enigma Variations.

It takes as much chutzpah to create a conducting career as to get elected president. In the musical scheme of things, Silverstein's conductor's star rose above the fray rather late, after decades in the violin sections of the symphony orchestras at Houston, Denver and Philadelphia, finally attaining concertmaster with the Boston Symphony and conducting that orchestra frequently as well. Did he have an artistic vision? He still does, and Sunday afternoon's audience at the California Theatre got it.

No matter the gorgeous soaring melodies and arpeggios of Vaughn Williams' Lark, it is a tough way to open a program. Rhapsodic and soft-spoken, it asks the audience to trust its yearning quietude, which soothes rather than excites the senses. Even its one familiar folk tune extended the pastoral spell. But here, Joe had us at hello, speaking with authority in the most circumspect way. If it seemed the wind and brass piped up a little too loudly, Joe paid no heed and always cut through with his soulful 1742 Guarnerius.

The Mozart is called "Turkish" because the third theme after the rondo tune in the last movement echoes the Janissary band that had entered European music at the same time the Ottoman crescent popped up in Parisian boulangeries as the croissant. In this case, however, the Turkish percussion was deployed in the cellos and basses. Meanwhile, Silverstein and the small orchestra loved the guileless charm and complete assurance that spilled from the 19-year-old composer's heart, and were loved by the room in return. Silverstein accepted the audience's invitation with a flawless romp through the preludio from the Partita in E by Bach.

Much praise was deserved by conductor and orchestra alike for the Elgar, one of the most cheeky and vivacious symphonic works to appear at the start of the 20th century. All the characters sketched by the composer enjoyed their moment under the lights and with the gorgeous sound of the orchestra flattered by the California Theatre's acoustics. Especially memorable were the first variation, a loving picture of the composer's wife, Caroline Alice, the deeply reverent and inspired impression of his best friend, the publisher A.J. Jaeger (called Nimrod after the "mighty hunter" of Genesis) and the swaggering Falstaffian finale, a self-portrait. (The latter enjoyed an extended life in the composer's later Falstaff—Symphonic Study in C Minor.)

An overlooked service provided by Symphony Silicon Valley is the opportunity to hear the orchestra recorded during its concerts by clicking on the link Listen to Music at its website, www.symphonysiliconvalley.org. There you will find, for one example, David Amram's Variations on a Song by Woody Guthrie, which was premiered at the start of the current season. (Amram, by the way, is currently preparing another SSV premiere for next season, a piano concerto for Jon Nakamatsu.)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|