home | metro silicon valley index | movies | current reviews | film review

Strand Releasing/Rialo Pictures

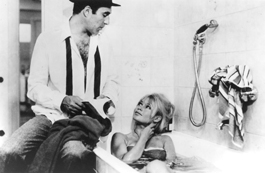

BATHING BEAUTY: Brigitte Bardot tempts Michel Piccoli (and everyone else) in 'Contempt.'

Ooh La La

A new book describes our love affair with the idea of France onscreen

By Michael S. Gant

RICK AND ILSA took comfort knowing that they would always have Paris. Lately, however, the French have being letting the rest of us down. Nicolas Sarkozy ran for president of the Fifth Republic on a platform of more work and less play—and won. Miss France was forbidden from competing in the Miss Universe pageant because she had posed, dishabille, for some suggestive photos with a carton of melting yogurt. Most shockingly, the French took the unthinkable step of banning smoking in cafes.

Admittedly, Sarkozy is trying to make amends by carrying on a very public affair with a rock-groupie heiress, but Franchophiles remain dejected. No matter how benighted American life, politics and culture have become, we always figured we could look to France as a beacon of intellectualism, socialized medicine (as Metro's Richard von Busack notes, the patient in The Diving Bell and the Butterfly automatically rates "a beautiful, passionate speech therapist"), eight weeks of annual vacation, sexual liberation, haute cuisine and acrid clouds of Gauloise smoke.

That wonderful image of sophistication and savoir-faire may always have been something of an illusion, but as any good French philosopher would tell you, theory trumps practice every time.

And how did we learn to love the French with such abandon? At the movies. Or so argues film and history professor Vanessa R. Schwartz in her fascinating new book, It's So French! Hollywood, Paris, and the Making of Cosmopolitan Film Culture. According to Schwartz, the image of France in both French and American post–World War II films promoted a spirit of modernity and cosmopolitanism that helped to internationalize film production and distribution.

Schwartz begins with a cycle of "Frenchness" films in the 1950s—An American in Paris, Gigi, Moulin Rouge, et al.—in which Hollywood embraced both the high art (Van Gogh in Lust for Life) and mass culture (the posters of Toulouse-Lautrec) of the French Belle Époque of the late 1800s and early 1900s. By concentrating on the most beloved and enduring image of French modernity, from the Impressionists to the can-can, these films allowed Hollywood to elevate itself by association and, at the same time, show off the advances in color and widescreen technology that it hoped would counter the growing popularity of TV.

In order to take full advantage of the architectural totems of Paris, Hollywood started location shooting in the City of Lights, a major step that pointed the way to the international English-language productions of the 1960s. The tourist montage in Funny Face, for instance, sends Fred Astaire, Audrey Hepburn and Kay Thompson, in three-column split screen, around the city until they converge on the Eiffel Tower. These brightly hued boulevards showed off postwar recovery and prosperity in contrast to the bleak black-and-white back streets of Italian neorealism.

The immense popularity of these Frenchness films (Gigi set attendance records and won nine Oscars) was augmented by the Cannes Film Festival, which started in 1939 but immediately took a wartime hiatus until 1946. Billing itself as Hollywood on the Riviera, the festival mixed red-carpet events with "spontaneous" photo sessions on the beach that showed the stars enjoying the kind of relaxed frivolity in which the French specialize. A charming publicity shot from 1953 captures a supine Kirk Douglas in a Speedo admiring the charms of a teenage, bikinied Brigitte Bardot. The controlled mayhem of the Cannes photographers spawned the paparazzi who eventually would become Britney Spears' ambulance chasers.

Significantly, Cannes drew film producers, directors and stars not just from Hollywood but also from around the world. Thanks to the Cannes effect, film production started to transcend borders.

No star was more important to Cannes, and France, asserts Schwartz, than Bardot—a.k.a. the "Eyeful Tower"—whose fame from 1956 to 1965 was extraordinary. Although it bombed on its first release in France, Roger Vadim's racy trifle And God Created Woman proved to be a sensation in the United States, doubling the box-office take of Marty, even in Midwestern theaters. French films in the United States were immune from the strictures of the Production Code and gave Americans a taste of sensuality and skin they couldn't get in homegrown movies. Schwartz quotes Time magazine's fruitful metaphor: "Her round little rear glows like a peach, and the camera lingers on the subject as if waiting for it to ripen." Bosley Crowther of The New York Times was more discrete: "She is a thing of mobile contours."

Bardot represented, like James Dean in America, a new generation of modern youth. As Schwartz writes, "Bardot pulled France out of the Belle Époque and into the flashy red sport cars of the leisure culture of the midcentury." Her appeal was especially vital to the French culture industry, which wanted to prove that it could represent the leading edge of modernity in a global economy increasingly dominated by American cultural brands.

Bardot's image of freshness, insouciance and liberated ways inspired the young French critics who would go on to create the New Wave of the 1960s. François Truffaut gushed, "She inaugurated a new moment in the cinema." Schwartz also quotes Lillian Gerard, a programmer at the Paris Theater, deflating the New Wave enthusiasm for Bardot: "a longhaired unwashed girl of good contourism who brought down the French intellectuals on their dirty knees"—worshipping both sex and success.

Bardot entered the New Wave in Jean-Luc Godard's Contempt (1963), an attempt to cash in on the movement. Her star status guaranteed a big budget, but in a symbolic gesture of defiance, Godard killed off her character in a car crash, her head lolling over the side of one of those flashy red sports cars. It was the end of "Bardolatry." The New Wave slipped into the art-house ghetto, while French mainstream film was subsumed in the so-called "hybrid" productions of the 1960s—expensive Euro-American spectacles that called no country home.

IT'S SO FRENCH: HOLLYWOOD, PARIS, AND THE MAKING OF COSMOPOLITAN FILM CULTURE by Vanessa R. Schwartz; University of Chicago Press; 259 pages; $25 paperback

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|