home | metro silicon valley index | movies | current reviews | dvd review

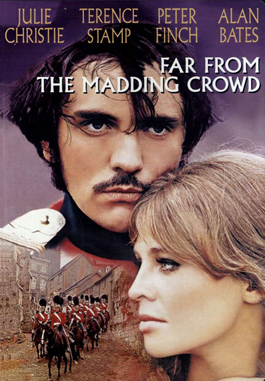

Far From the Madding Crowd

One disc; Warner Home Video; $19.97

Reviewed by Michael S. Gant

Now that Terence Stamp's grizzled, white-haired visage has turned up in everything from Wanted to Yes Man, the new edition of 1967's Far From the Madding Crowd reminds us how he became a '60s icon and romantic lead in the likes of Billy Budd, The Collector and Modesty Blaise, before disappearing in India in the wake of a failed relationship with model Jean Shrimpton. In the 1967 big-scale screen adaptation (nearly three hours) of Thomas Hardy's novel, set in mid-19th-century rural England, Stamp plays caddish Frank Troy, one of three men smitten with Julie Christie's Bathsheba Everdene (Hardy was always one for overdetermined character names), a beautiful young woman who has just inherited a country estate.

Her other two suitors are hunky herder Gabriel Oak (Alan Bates) and older William Boldwood (Peter Finch), the neighboring member of the landed gentry. Faced with the prospect of the rich and sensitive Boldwood, the poor but sensitive Oak and the poor and insensitive Troy, Bathsheba naturally picks the bad boy. Their tempestuous relationship quickly turns to emotional rot. Meanwhile, Boldwood mopes about the countryside, and Gabriel takes care of the sheep—he cures a mass outbreak of bloat by stabbing all the sheep in the gut. As always with Hardy, the misery starts early (Gabriel is ruined in the first few minutes when his sheepdog herds his flock over a cliff) and continues unabated, with fires, poverty, torrential rain, bad harvests, disease and debt.

The scenery is beautifully photographed by Nicolas Roeg, but this would-be epic doesn't have even the stately momentum of Barry Lyndon. As is too often the case with Hardy adaptations, all the dramatic incidents are just strung together into a litany of suffering; the same problem hobbled the recent BBC adaptation of Tess of the d'Urbervilles. Without Hardy's detailed omniscient narrator, the characters end up without plausible emotional trajectories. Stamp makes a handsome bounder, but the famous scene in which he woos Christie by thrusting and parrying at her with his saber looks risible today. Finch gives the best performance, making Boldwood's unrequited love seem genuinely painful. But director John Schlesinger was an odd choice for the material—what could the director of Darling, Sunday, Bloody Sunday and Midnight Cowboy have seen in Hardy's rustic melodrama? If ever there was a project for David Lean, this was it. No extras.

Click Here to Talk About Movies at Metro's New Blog

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|