home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | visual arts | review

© 2007 The M.C. Escher Company-Holland. All rights reserved. www.mcescher.com

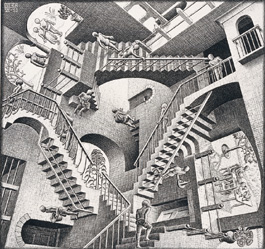

Going nowhere fast: M.C. Escher's 1955 lithograph 'Liberation' shows his fascination with optical illusions.

The Rise Of the House of Escher

M.C. Escher's trick worlds push the limits of visual illusion

By Michael S. Gant

LONG AGO, dorm rooms with art posters instead of rock posters on the wall favored two artists: the gilt-edged Klimt and the hard-edged M.C. Escher. The fame of Dutchman Escher (1898-1972), filtered through copious reproductions and books (mostly notably Douglas Hofstadter's Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Braid), now exceeds the usual realm of art-world aesthetics. Iconic images, such as the 1953 lithograph (Relativity), in which featureless pod-people traverse staircases that seem to go two directions simultaneously, have made him a favorite of mathematicians, engineers and logicians. In their rigorous use of illusionist perspective, Escher's prints and lithographs offer more opportunities for analysis than simple appreciation. They also provide endless fodder for gift-store merchandise, from date books to foam-rubber jigsaw puzzles for precocious toddlers.

A hawk-nosed glowering man with oceanic wavy hair, judging by some of his self-portraits, Escher trained in architecture and decorative arts, and early on mastered the technique of woodblock printing. His skill at the medium is well displayed in some of the early pieces on display at the San Jose Museum of Arts' new show "M.C. Escher: Rhythm of Illusion." His lines are precise, and his scenes are filled in with dense detail, like scientific illustrations; his wood engravings (both 1935) Grasshopper and Scarabs are both models of close attention to nature's detail. No sign of handwork of the kind found in the more dynamically staged woodcuts of a contemporary like Rockwell Kent are visible.

In an early series of woodcuts, from the 1920s, called "Creation," his vertical arrangement of the profusion of life, from the coral and fishes of the sea to the birds in the sky above, looks more like a textbook lesson on evolution than a devotional statement. However, a gentler side does emerge in a prelapsarian scene of Adam and Eve in The Sixth Day of Creation. We see the ur-couple from behind, his hand draped companionably around her ample hips, while a kitty cat, of all creatures, rubs up against her ankle—a very domestic paradise.

Escher spent most the 1920s and half of the 1930s in Italy, before fleeing the depredations of the fascists. He ended up in Switzerland, then the Netherlands. About 1936, he started to explore the powers of illusion that the 2-D surface offered. Using techniques of optical illusion like the Necker Cube and the Penrose Staircase, Escher fashioned complex, populated versions of these simple but baffling tricks. These prints remain fascinating for their combination of architectural specificity, wondrous optical paradox (literally, you can't believe your eyes) and Kafkaesque quality as robotic figures strive endlessly to ascend, but always manage to descend at the same time, and meet themselves coming and going.

Escher also experimented in various kinds of tessellations, or regular tile patterns that can extend indefinitely. Often, Escher would create interlocking light-and-dark images that could subtly morph as the eye moves across the artwork, sometimes changing from flat patterns to seemingly 3-D creatures and forms. In one of the best of these, Circle Limit IV, grotesque winged bats fit snugly into the contours of white angels, starting large at the circle's center and receding to more and more and smaller and smaller repetitions at the edge—a neat example of good and evil intertwined, reconciled even.

Here and in the case of the famous Rippled Surface, the exhibit includes preliminary sketches showing Escher's flawless draftsmanship and meticulous preparation. Many of Escher's more extreme forays into optical frontiers may have influenced in turn the Op Artists of the 1960s, who plunged into complete abstract worlds, and who are the subject of a companion exhibit in the museum's main downstairs gallery—more on this show next week.

M.C. Escher: Rhythm of Illusion runs through April 22 at the San Jose Museum of Art, 110 S. Market St., San Jose. (408.271.6840)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|