home | metro silicon valley index | movies | current reviews | film review

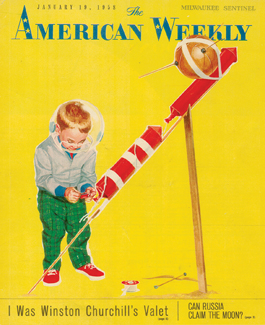

So Easy a Kid can do It: American popular culture quickly responded to the Soviet space threat

Close Encounters

Cinequest documentary 'Sputnik Mania' recalls how the world almost scared itself to death on the way to the Space Age

By Richard von Busack

OF THE films coming to Cinequest, Feb. 27–March 9, that I have had a chance to screen, one of my early favorites is Santa Cruz director David Hoffman's smart documentary Sputnik Mania, all about that strange time when a tiny orbiting bit of metal spooked the United States into a space race.

On-camera, Walter Cronkite offers his viewers a choice: "Do we end in a nuclear war or live in constant fear of one?" Faced with these two possibilities, the human race nobly chose the latter.

Echoes of the great fear have persisted into our day. Sputnik Mania, edited and co-produced by John Vincent Barrett, another Santa Cruzan, demonstrates how the worst of that panic began. Hoffman presents a wealth of archival footage here—including some of the most dismally hilarious civil defense and propaganda films this side of The Atomic Cafe. The International Documentary Association liked it so much it awarded the film top honors for its use of those old reels.

Adapting co-writer Paul Dickson's book Sputnik: The Scare of the Century, Hoffman follows a dangerous—nearly lethal—year in the history of the world. The two major powers, the United States and the U.S.S.R., were led by lumpy, bald ex-soldiers so physically alike that they could have been brothers. Through the media available at the time, they took shots at one another. Dickson and Hoffman repeat the claim that the U.S.S.R.'s leader, the truculent Nikita Khruschev, had repeatedly said his nation would "bury" the United States. (I may be wrong, but I've heard that Soviet slur translated as "We will leave you in the dust," changing an undertaker's threat to the boast of a race-car driver.)

Though troubled by fears of the atheist beet farmers waiting to toss dirt on us, America, under the leadership of Dwight Eisenhower, still drowsed through the consumerist picnic that was the 1950s. That picnic was about to be disturbed by ants. Red ants.

On Oct. 4, 1957, the Soviet Union announced the launching of the first space satellite: Sputnik, a beach-ball-size orb with four protruding antennas. Traveling at 18,000 mph, the satellite broadcast its finchlike beeps to the globe. Measured applause for this scientific feat occurred everywhere from The New York Times to John Glenn ("It's out of this world!" Glenn jested, sort of).

Now, for those considering the Injured Party as a possible alternative name for the Democrats, I can say that, as someone raised to feel that the Blue Team is always the one that has to clean up after the Elephants, Sputnik Mania comes up with some little-known history. The Republican Eisenhower tried to frame Sputnik as a triumph of science—"It does not raise my apprehension one iota," he said. Seizing the issue, Democrats (and right-wing fulminators, tired of Ike's moderation) blew up like proverbial rockets themselves. Later, President Lyndon Johnson noted in his diary, "I felt uneasy. In Texas, we live close to the sky. In some ways our skies seem alien." Democratic Sens. Hubert Humphrey and Scoop Jackson scolded the White House for not treating Sputnik as an emergency. The press also went nuts. Sputnik Mania quotes a particularly fragrant San Francisco Chronicle editorial claiming that Sputnik was "a frightening toy in the hands of child-like men."

And then the second blow fell. On Nov. 3, 1957, the Russians launched Sputnik 2, containing a live dog named Laika. The drama of this event electrified the world. The satellite, quickly nicknamed "Muttnik," turned tragic when it became apparent that the U.S.S.R. had better plans for getting the dog up than for bringing him home. Secretly, the American intelligence services worried about the Soviets' ability to send up a 1-ton-plus payload, with enough room for a nuclear warhead.

The Cold War deepened as America struggled to catch up with the Russians. American amateur rocketeers blew their digits off in homemade missile experiments ("They were pipe bombs with fins," remembers one later rocket scientist). And Eisenhower reluctantly turned to the military to develop better missile technology. The head man was the brilliant ex-Nazi Wernher von Braun, who had been busy during the war figuring out ways to renovate London with V2 missiles.

Hoffman's rewarding documentary assembles everything from vintage toy commercials to interviews with Sergei Khruschev (Nikita's son). Since you're alive to read this, you know the film has a happy ending. The two elderly rivals met at Camp David and admitted to one another that they were being pressured by their generals to blow their economies on new weapons. Thus Eisenhower created NASA, a civilian agency to explore space. This commenced the ascent to the moon, and the terror of Sputnik gave way to a triumph meant for all mankind. Then an impressionable ex-governor of California got the wrong message from a George Lucas movie ... and the rest is history.

Cinequest Updates: Last-minute Maverick Spirt Award winner John Leguizamo will appear at the festival on March 3 at 7pm at the California Theatre in San Jose. Plus, new Maverick winners Michael Keaton and Danny Glover have just been announced—see details on page 70.

![]() SPUTNIK MANIA screens as part of Cinequest on March 3 at 7pm and March 4 at 9:30pm, both at the San Jose Rep, 101 Paseo de San Antonio, San Jose. Cinequest runs Feb. 27–March 9; see www.cinequest.org and check www.metroactive.com for festival updates. (Full Disclosure: Metro is the official print sponsor of the festival.)

SPUTNIK MANIA screens as part of Cinequest on March 3 at 7pm and March 4 at 9:30pm, both at the San Jose Rep, 101 Paseo de San Antonio, San Jose. Cinequest runs Feb. 27–March 9; see www.cinequest.org and check www.metroactive.com for festival updates. (Full Disclosure: Metro is the official print sponsor of the festival.)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|