home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | visual arts | review

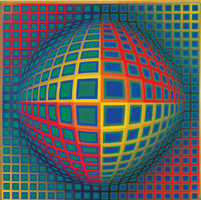

Battle of the bulge: Victor Vasarely's 'Vega-Nor' seems to pop out of the picture plane.

Special Op

The San Jose Museum of Art samples the history of Op Art

By Michael S. Gant

HUNGARIAN artist Victor Vasarely, the father of Op Art, once asked, "Does not aggressing the retina in fact make it vibrate?" That notion underlies the movement, which used simple formulas for the arrangement of lines, dots and squares to create visual fields that tricked the eye into believing that they were vibrating, oscillating and pulsing with forms and colors that didn't really exist on the canvas. Op Art, one letter purer than Pop Art, grabbed the headlines with the 1965 Museum of Modern Art show called "The Responsive Eye," burned out quickly and was relegated to the backwash of '60s art movements that had outlived their usefulness.

"Op Art Revisited," a traveling show from New York's Albright-Knox Gallery, now at the San Jose Museum of Art, tracks a few progenitors of Op Art, showcases some seminal works and offers enough samples of later optical experiments to argue that the movement is alive and well, if still marginal. Op Art first surfaced with Marcel Duchamp (as did most of 20th-century art), whose painted glass construction To Be Looked at (From the Other Side of the Glass) With One Eye, Close to, for Almost an Hour (1918) included a pyramid shape made from crisscrossing colored lines that induced an unstable moiré pattern, one of the primary tricks of the Op Art to come.

The exhibit proper begins with two later works by artist and influential teacher Josef Albers. Homage to the Square: Terra Caliente (1963) nests four squares in a flat field, setting up subtle contrasts by the juxtaposition of closely related colors. Structural Constellation F.M.E. No. 3 (1962) depicts a white-line geometrical "impossible object" that flips back and forth in orientation—the eye can't come to a rest and make a definitive judgment. For decades, Albers' students at Black Mountain College and Yale did exercises in which minute progressive changes in line weight produced effects far beyond their repetitive structure.

The most successful follower of that rigorous method of using nothing but black-and-white elements was British artist Bridget Riley, who specialized in the close accumulation of mathematically regular curves. She is represented by Drift No. 2 (1966) in acrylic in which great wavy ribbons in black and gray impart such a powerful 3-D effect that the canvas appears to be literally rippled and not flat. In later years, Riley turned to color-stripe paintings, but Vein (1985) lacks the zing of her black-and-white pieces.

French artist Jean-Pierre Yvaral employs sculptural elements such as arrays of cords mounted in front of a backdrop of closely spaced black lines to induce a black-and-white moiré effect so extreme that Acceleration No. 15 (1962), true to its name, never stops moving. In some cases, Op artists went kinetic, mounting their black-and-white patterns on motors so that the rotation produced hypnotic swirls, as in Francis Celentano's Kinetic Painting III (1967), a full flowering of Duchamp's Rotary Glass Plate of 1920.

Among the Op followers who played with the various ways in which complementary colors can be altered simply by the backgrounds on which they are placed, Richard Anuszkiewicz remains the most impressive. His Water From the Rock (1961-63), a circular swirl of distorted rectangles of fluorescent color, echoes psychedelic rock posters, minus the band names. His Temple to Albers, from 1984, keeps the tradition alive with vertical panels of brilliant gold framed by thin black lines—they look like classical columns in some heavenly vision of pure light.

The real show-stopper is Vasarely's Vega-Nor (1969), a large painting in which a flat grid of small multicolored squares grows into a great sphere in the center that seems to bulge out of the canvas. Vasarely studied physics, and his painting resembles the diagrams of space-time fields distorted by the gravitational pull of planets in textbooks on relativity.

The most intriguing thought about such a survey in Silicon Valley is the way the Op artists used binary processes to "program" their paintings as if they were visual computers. Vasarely, intrigued by how much could be achieved in this way, wrote, "White and black, yes and no, it is the binary language of cybernetics, making possible the building of a plastic bank in electronic brains. White and black, it is the indestructibility of art-thought." In a recent book about her father (who died in 1997), Michèle-Catherine Vasarely wonders, "What he would be doing today, with the aid of the technological tools he mimicked in his mind long before they existed."

Op Art Revisited: Selections From the Albright-Knox Art Gallery runs through April 22 at the San Jose Museum of Art, 110 S. Market St., San Jose. (408.271.6840)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|