home | metro silicon valley index | music & nightlife | band review

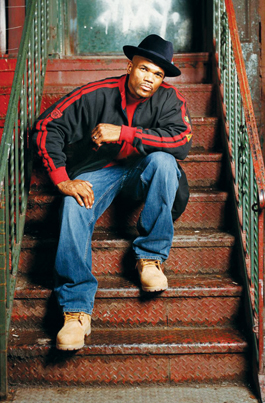

STILL RAISING HELL: Run-D.M.C.'s Darryl McDaniels knows hip-hop can be better than it was back in the day.

Son of Byford

Seminal rapper Darryl McDaniels talks about the birth of hip-hop and Run-D.M.C.'s route to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

By Gabe Meline

WE ARE the hip-hop generation. That's what they call us, at least. We're the ones for whom hip-hop was never a threat. To whom hip-hop never was anything but an inspiration, a shared language, a code of conduct, an infinite subject matter, an empowerment. We grew up through hip-hop, yes, but more importantly, we grew out through hip-hop.

We owe a lot of it to Run-D.M.C. We're the ones who heard "Peter Piper" and "Proud to Be Black" and thought, damn, that's way more raw than Richard Marx. Why are all the songs on the radio about love? I'm not in love, man. If anything, I'm in traction. A whole lot to say and no way to say it. "It's Tricky"—now, there's a song. Dudes just rap what's on their mind, straight up.

We would spend hours transcribing their lyrics, those two dudes, and we'd argue about who we liked more. Run was easily excitable, prone to overload. D.M.C. was a little raspier, a little wiser-sounding. "Son of Byford" told it all: he had a family, he had friends and he had rhymes—which, as we loved to repeat on the playground, were McDaniels, not McDonald's.

I was in the D.M.C. camp. He seemed more real. I first learned about Jesse Owens and Malcolm X though D.M.C. I learned about everyday life on the other side of the country and about brotherhood, and a lot of other things that Richard Marx wasn't talking about. So when Darryl McDaniels, the D.M.C. in Run-DMC, called my house, I allowed myself to be a little anxious.

McDaniels is on a national lecture tour in advance of the group's April 4 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, talking about the history of hip-hop, and there may be no person aside from his band mate Run with better experience to draw upon. Even so, McDaniels was hesitant to do lectures until he talked to Chuck D from Public Enemy. "For the longest time I was like, 'No, no, no, no, no,'" McDaniels tells me from his home in New Jersey. "But then Chuck was like, 'Yo, D, you need to go do lectures, man. You're sayin' something people need to hear.'"

McDaniels' story offers a look into hip-hop before the music industry seized it and promoted it coast to coast. He talks about meeting Run and Jam Master Jay on 205th Street and Hollis Avenue, hanging out and writing rhymes. He talks about setting up DJ equipment in 192 Park in Hollis and writing rhymes. He talks about getting kicked out of the hallways of his apartment building and retreating to the alley and writing rhymes.

"With or without the music business, before rap was on the record, it was already there," McDaniels says, adding that college kids born the year of Run-D.M.C.'s breakthrough album Raising Hell might not recognize the organic genesis of hip-hop. "They think it's all about Billboard magazine, and havin' your record in high rotation on the radio and havin' a good label. It ain't nothin' like that. It's about havin' something to say in a creative way. So I'm thinkin', if these kids can hear, maybe hip-hop would get more creative, innovative, inspirational, motivational and educational."

Inspiration and motivation aren't exclusive to McDaniels' era of hip-hop, but he points out that they used to be ideals rather than accidental byproducts. The world is filled with well-educated rappers fronting about drugs and violence; in hip-hop's early days in New York City, it was the other way around.

"Afrika Bambaataa and the Zulu Nation was a street gang in New York, but they turned something bad into something good!" McDaniels emphasizes. "Most of the rappers that made positive records were drug dealers, stick-up kids and murderers, but when they stepped to the microphone, they would say, 'Don't do what I'm doin'! There's a better way for you! Go to school, read a book, learn about your history!'"

Run-D.M.C. often gets credit along with producer Rick Rubin for breaking down the wall between rock and rap with guitar-driven tracks like "Rock Box" and the Aerosmith collaboration "Walk This Way." The idea wasn't just some marketing ploy, McDaniels says, but a natural cohesion with the "white rock kids" who were early fans: "I'm talkin' about kids that were listening to Lou Reed, the Ramones, Sid Vicious. We had those punk-rock kids in our shows before we even put a guitar on it, because rock & roll and hip-hop is brother and sister—controversial, innovative, creative, energetic.

"It's the same feelin'," McDaniels continues excitedly, "but different expression. These kids was lookin' at Run-D.M.C., and sayin', 'Yo, I know this! This is familiar to me! This is me!' 'Cause it wasn't a black-and-white thing. We was rappin' about everything—sneakers, chicken, collard greens. You know what I'm sayin'? We was rappin' about what everybody was livin'. When I do my lectures, I talk to the kids and say, 'This ain't a black-and-white thing, a rich or poor thing. Hip-hop, whether in Beverly Hills or in the ghetto—we're there together for those hours at the concert or listening to a rap record, we all on the same level. After it's over, we can look at each other and say, 'What's next?'"

What's next for Run-D.M.C. is being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame this year, an inevitable honor (last year, Grandmaster Flash became the first hip-hop artist inducted). Though most honorees perform at the induction ceremony, Run-D.M.C. has been disbanded since the fatal shooting of DJ Jam Master Jay in 2002, and McDaniels responds immediately and somberly to the idea that the two remaining members perform. "We can't," he says. "We can't do it without Jay. We can't be runnin' around without Jay. We was more people than just music."

McDaniels, who was diagnosed in the late '90s with a rare larynx disorder that gives him a high-pitched voice, has won a Congressional Award for his work in foster care and adoption services after finding out that he, too, was adopted. (He does not plan to change the lyrics to "Son of Byford.") Hip-hop remains his first love, although it's hard to gauge how avidly he follows the genre he helped create. He balks at the success of Lil' Wayne, and says the last new rapper he was impressed by was DMX, who began making albums more than 10 years ago.

"Where do I see hip-hop heading?" McDaniels asks. "That's a good question. I have no idea where it's heading. I just know what we can do with it. 'Cause—put it like this—I don't want hip-hop to be like it was back in the day. I want it to be better than it was back in the day. 'Cause I know it can be."

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|