home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | stage | review

Photograph by David Allen

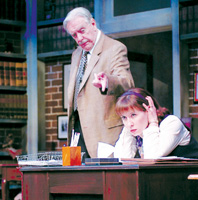

Dictator of dictation: Ken Ruta's Francis Biddle make work tough for his secretary, Sarah Schott (Amanda Duarte).

History's Filter

A young secretary wrestles with a great man's memories in TheatreWorks' 'Trying'

By Marianne Messina

VERY EARLY in the two-character play Trying, Judge Francis Biddle (Ken Ruta) informs his new secretary, Sarah Schorr (Amanda Duarte), that when she was born he was 56 years old: "We can't help but find each other extremely trying." And they do, in this muscular TheatreWorks production based on the real-life Biddle and written by Joanna McClelland Glass, who spent a trying year in the late 1960s as Biddle's secretary (the last year of his life). The story takes place in the shadow of great history. As attorney general under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Biddle oversaw the Japanese internment during World War II, and later under Truman, he served as a judge at the Nuremberg trials.

But sequestering Biddle and Sarah in his converted hayloft of an office among wall-to-wall bookshelves spilling with books (Duke Durfee, scenic designer), Glass lets the relationship obscure the history. Reduced to snippets of dictation for his memoirs, which Sarah takes down while sitting in front of Biddle's expansive desk, that history has faded like the somewhat feeble, often forgetful and tryingly cantankerous Biddle himself. At first, the between-the-scenes sound design also erases the larger history—to uncertain effect. Sometimes, the buoyant Proctor and Gamble-style commercials about household products and home decoration just seem out of place.

The play brings us the clash between old age and youth, between provincial culture and Ivy League networks, but the dialectic match-up is far from equal. Fresh off the Canadian prairie, Sarah is overwhelmed by Biddle, just as her character is dwarfed by that of the aging judge. Biddle's clear convictions, his fame, his forceful personality, his irresistible expressions (when his wife is angry "the flies leave the room") dominate the action. And his internal struggle with letting go of such a vital life takes center stage.

Of course, Sarah's plucky persistence ("Madam, you are nothing if not single-minded") earns her an underdog's sympathy. But we see Sarah only as Biddle sees her. Perhaps sticking too close to autobiographical details, Glass has Biddle cut Sarah off before she can share much about her personal life ("You'll find I am not interested in the husbands"). Our only sense of how Sarah interacts with the world comes from watching her defensive volleys under Biddle's onslaught of complaints about her presumed attitudes, objections to her split infinitives and criticism of word choices like "voracious reader"—"I prefer that one eats 'voraciously' and reads 'voluminously.'" Duarte holds her own as the no-frills Canadian prairie girl, champion of the work ethic and the self-made man. She's nearly as colorless as Biddle says she is. (Costume designer Jill Bowers hits it right with Sarah's prosaic gray jumper, lengthed good-girl style to the knee.) The bond that grows between her and Biddle would be a hard sell were it not for the touch of innocent vulnerability Duarte adds to the mix.

For the most part, however, this is Ken Ruta's show. Ruta breathes his part, every stutter, tremor or sly sidelong glance. He goes from a mumble to the queen's own elocution within a sentence; his delivery can reflect both snobbery and relish for the language; a single glance around his glasses can be part humble, part crafty. When Biddle starts a statement with his dramatic "Madame ...," the anticipation is delicious. Humor falls out naturally and continuously, yet the play strikes deepest when Biddle fills the air, suddenly gone still, with a passage from Shakespeare's Life and Death of King John on grief. The play has topical moments when Biddle speaks of his unhappy run-ins with "muscular Christianity" or points out that the Japanese internment issue taught him never to trust "the cliché 'military necessity.'" Framed as a relationship forged over a vast divide, this play keeps coming back to the unraveling—of a very rich life, of an accumulation of culture. Glass waited 40 years to write this from a perspective closer to Biddle's. And the lingering sense, as simple, persistent Sarah moves in behind Biddle's desk, is that we build empires and lives simply to unbuild.

Trying, a TheatreWorks production, plays Tuesday (except March 27) at 7:30pm, Wednesday-Friday at 8pm, Saturday at 2 and 8pm and Sunday at 2 and 7pm (no 7pm show April 1) through April 1 at the Lucie Stern Theatre, 1305 Middlefield Road, Palo Alto. Tickets are $20-$55. (650.903.6000)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|