home | metro silicon valley index | music & nightlife | review

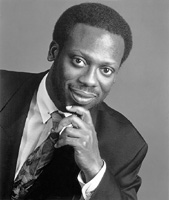

On the podium again: Leslie Dunner returned to lead Symphony Silicon Valley over the weekend.

Fanfare

Symphony Silicon Valley's Sunday concert proved again the acoustic advantage of the California Theatre

By Scott MacClelland

THE SOLO PERFORMANCES during Sunday's matinee by Symphony Silicon Valley all came out of the orchestra itself. They were heard when Leslie Dunner returned to the podium to guest-conduct Maurice Ravel's dubiously named Boléro, Zoltan Kodály's comedic Háry János Suite and Aaron Copland's postwar Third Symphony. The concert also provided some worthwhile lessons for those willing and/or able to use them. Outright acclamation followed the Ravel that opened the program. Among those in the audience were several who remember when the erstwhile San Jose Symphony played it at the Center for Performing Arts. (Nothing underscored the difference between that old barn and the acoustically efficient California Theatre more than the impact achieved as the "orchestral texture without music"—to quote the composer—grew louder and more colorful.)

After the work's sinuously repeating melody is heard on solo winds and brass—arriving at back-to-back alto and soprano saxophones featuring the sweetly engaging tone of visiting artist William Trimble—there follows a weird-sounding episode that puzzled some in the audience. "What instrument is that?" a listener within earshot wondered out loud. (For the purpose of this article, I put the question to hornist Wendell Rider during intermission. He said tersely, "Horn and piccolo in sevenths." Immediately, Rider and a colleague from the contrabass department got into a debate over how that passage should be properly played.)

Dunner clearly had an idea of how loud loud is, building skillfully to fortissimo at the opposite end of the performance, and getting it, to the pure delight—including cheers and whistles—of the full house audience. Straightaway, he conducted the Kodály with careful attention to the details of this equally colorful score, also laden with solos within the orchestra. One of those was played with rustic character by principal violist Patty Whaley, dipping down into the cello register of her instrument and making it speak with a gutsier voice than is typically heard.

But the cimbalom, used for local Hungarian color in two of the suite's movements, proved inadequate. For its first appearance, in Song, amplification through house loudspeakers both displaced its image from stage center and enlarged it out of orchestral proportion. Yet in its second outing, in Intermezzo, it was all but drowned out. Given that it could be adequately replaced by a piano—there was one onstage for the Copland—it would seem to make sense to find a better way to exploit its unique color. Hard hammers instead of the soft ones used here, and perhaps a reflecting lid, like one sees on grand pianos, might have done the trick, without artificial amplification.

The biggest lesson to be learned from Copland's beautiful score is probably useless, since the composer is no longer available. The last movement is backward, shooting its bolt—the famous Fanfare for the Common Man—at the start and leaving an underdeveloped, anticlimactic conclusion. That said, the expanded orchestra's performance was both full-bodied and transparent, qualities for which Copland is widely respected among musicians and music-lovers alike. And notwithstanding Copland's populism—with allusions here to his Rodeo dances—its complexity challenges, and rewards, audiences who make the effort to listen up and pay extra attention.

Symphony Silicon Valley's upcoming concerts schedule include the Verdi Requiem at the end of the month and, the following week, a benefit celebration of San José State's 150 anniversary.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|