home | metro silicon valley index | features | silicon valley | feature story

Bette Davis Eyed

One of cinema's all-time greatest actresses would have turned 100 on April 5, and the Stanford Theatre is honoring her career with a retrospective. But just what was behind those peepers that Kim Carnes sang about?

By Richard von Busack

IT WAS Karl Freund, the cinema-tographer, who first noticed what was to become a major phenomenon in the cinema. The New York office of Universal Studios signed a contract with a rising young stage actress who had made a splash in a production of Ibsen's The Wild Duck. It was thought that she would be good for a film version of Preston Sturges' stage hit Strictly Dishonorable. In mid-December 1930, she arrived in Los Angeles on the train.

She was small—105 pounds—and she blended in with the crowd. The story goes that no one from the studio greeted her, because no one on the platform looked much like movie star material. The actress in question, Bette Davis, said later that it was unfair. She was holding a lapdog in her arms, she said, and ought to have been recognized as an actress for that alone.

To Burbank Davis went. The studio's Carl Laemmle Jr. recalled what he saw when he had a look at her in the Davis biography More Than a Woman by James Spada; before him was "a girl without makeup, one who had never been to a beauty parlor, and whose eyebrows were thick and unplucked, whose long hair was wound up in back and broken only by two curls at her face."

Davis was from an artistic Massachusetts background. She was the daughter of a noted Boston lawyer, though an especially bitter divorce had reduced her family's circumstances.

She had always been popular with the young men; one of her school friends complained in verse: "This is the house where Bette lives. These are the cars that come to the house where Bette lives. There are the boys who come in the cars to come to the house where Bette lives."

She wasn't a prude, but nothing had prepared her for the hazing she'd get at as a new actress in town. She was described as "a little brown wren." She was sized up, and she was groped. Expecting to show off her elocution skills, she was instead commanded to show her legs. At one point, she was used as a kind of horizontal stand-in, as a director and crew contemplated and contrasted the kissing techniques of 15 male actors vying for a part.

Maybe the worst indignity was the casting itself. You have to ask yourself what a studio was thinking when it made a movie called The Bad Sister and then hired Bette Davis to play the good one. After watching herself onscreen in that film for the first time, Davis cried all way home, according to Spada: "My clothes were bad and my hair was abominable."

She was certain that the studio was ready to let her go. Instead, they raised her salary, apparently on the advice of Karl Freund. That leading light of German Expressionist cinema commented that the studio ought to keep her: "She has nice eyes."

Eye Rule

"Ferocious, and she knows what it takes to make a pro blush." The Jackie DeShannon/Donna Weiss song from 1974 became the monster hit of 1981. And Kim Carnes sang "Bette Davis Eyes" to Davis herself. The actress commented that she was glad that her grandchild had got to know about her life work.

Those eyes did have it; roguish or hostile, melting or threatening, "darting or fearful," as critic Molly Haskell noted in her film history From Reverence to Rape. There's also an off-kilterness to them; is she looking outward or inward? The famous anti-smile—V-shaped with cozy triumph, or halfed in Mona Lisa style was, Davis said, the result of nerves: "Embarrassment always made me have a one-sided smile," she wrote in her autobiography, The Lonely Life. What didn't show at first was the steeliness of a performer who persisted for more than 50 years.

In her last years, on talk shows and award shows, she was "making the pros blush" with a whiplike tongue and a refusal to tolerate fools. She survived even the push-mama-under-a-bus memoir, My Mother's Keeper, by her born-again Christian daughter, B.D. Hyman. It's clear: if Davis were alive today, she'd still be fighting her way to the camera.

I see on the IMDb that Davis had a comment about her last significant film, The Whales of August—a prestigious bore, in which she played the liberated, strong Libby Strong. Regarding her director Lindsay Anderson, Davis said: "I think he's a very talented man, but I think he's a difficult man to work with. He really prefers theater and not film, and that's a little depressing, I must say." And yet four decades before, she was grousing to the Algonquin Round Table that only fools took movies seriously.

It was Bette herself who helped prove film's possibilities to surpass the theater. She was an influence on the course of film history, with her desperate craving to act, and her willingness to fight the studio system, in person and in court. She wasn't frightened of the unladylike or the grotesque; what we call stunt acting is just a reflection of the willingness of Bette Davis to go beyond the shiny surface.

She was often punished in the last reel by the dictates of the film codes; often she vanished into the fog or into a backstreet set. "She was the Duse of alleys," one critic said, referring to the then-sacred figure of the theater actress Elenora Duse. Haskell counters that Davis's indomitable character herself is what matters, no matter what befalls her. "Whatever the endings that were forced on Bette Davis ... the images we retain ... are not those of subjugation or humiliation."

The Fourth Warner Brother

Davis was born April 5, 1908, a cool century ago, and her centenary is being marked by a spring-long retrospective at the Stanford Theatre in Palo Alto as well as by the release of a new DVD collection (see sidebars). The Stanford series shows the making of Bette Davis, her endurance over false tries and bit parts. The DVD set shows how her mix of fury and sensitivity kept her afloat as tastes changed.

Let's start with the beginning; the Bette Davis retrospective at the Stanford Theatre consists of 36 films (10 in new prints) from the 1930s, mostly from her formative years at Warner Bros.: "Five years on paper, 18 years of life," she called her time there. Dave Kehr, The New York Times' old-movie maven, has commented that Warner Bros. had a split identity. Then head of production, Darryl Zanuck, loved the torn-from-today's-headlines feverish material. So did Davis, who wrote that Warners was the only studio really dedicated to exposing social injustice.

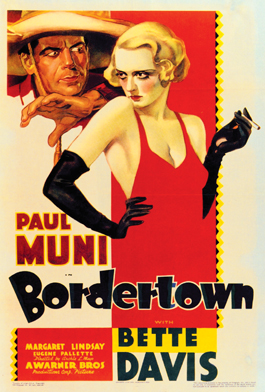

But two of the most accomplished directors there, the immigrants Michael Curtiz and William Dieterle, were more in the thrall of Lubitsch and Central European theater. Davis united this split by the persistence of her career. In her early years, she was the brassy working girl, the moll, the secretary, the "clip-joint hostess." In later years, Bette—like her rival Joan Crawford—haunted every shadowy melodrama. No wonder Bette Davis was called "The Fourth Warner Brother."

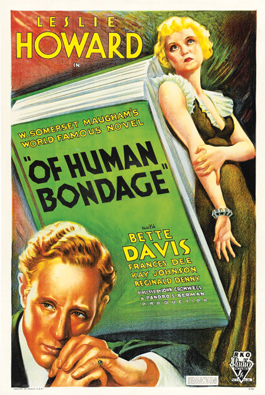

The Stanford Theatre's fest begins with Davis's first screen triumph, as Mildred in Of Human Bondage. Director John Cromwell pares down a large, semiautobiographical W. Somerset Maugham novel, concerning a club-footed doctor who is nearly destroyed by a piece of poisoned candy named Mildred. This Cockney tart manipulates him, flirts with him and almost destroys him. The right and proper angle to take on this story is to feel for the doctor (Leslie Howard), so dedicated and refined, in the clutches of a she-demon.

But that isn't what happens when you watch the movie. The part of Mildred was one that few actresses wanted. Davis yearned to be Mildred and fought to be loaned to RKO to play it. And when we see her Mildred—drawling, falsely naive, hot as a pistol, we certainly see her point. Some woman don't feel like being worshipped; some women can't tolerate weak men, a lesson that's always painful for the man in question.

Of Human Bondage is billed with Jezebel, which came in 1938 after Davis' career crisis as she faced age 30. She was on the far end of a streak of poor films that led her to sneak over the border to Canada, take ship herself to England and fight her contract with Warner Bros, in an English court. (The breaking point for Bette was a script titled God's Country and the Women, wherein Davis would be required to play a female lumberjack.) After this legal skirmish, both sides apologized, and Warner Bros.' Jack Warner gave her a raise and paid Davis' legal expenses.

There was a property the studio was interested in—a 2 1/2-pound novel called Gone With the Wind; Warner thought Bette would be right for the part. Fans, too, must have thought of Bette as Scarlett when they read the first line: "Scarlett O'Hara was not beautiful, but men seldom realized it when caught by her charm." The character suits the idea of Davis as a force: as someone who made her luck.

It didn't happen, though it remains one of the most enticing almost-ran bits of casting in movie history. And the manipulative heiress Julie Marsden whom Davis plays in Jezebel is remembered mostly as what her Scarlett might have been. This is true particularly in the most famous scene: Julie's scandalous appearance at the Olympus Ball in 1850, wearing a red skirt instead of the traditional white. William Wyler, Davis' lover as well as director—"the only male strong enough to control me," she said—brought out the inner side of Davis' acting. And here is a psychological depth that matched the outward fury and brazenness of Bette's previous work.

Looked at as a whole, Davis' career was a success, and she never treated work as beneath her. All About Eve was her famous comeback, though it's worth repeating Molly Haskell's comment that in the role of Margot Channing, "Davis is declared obsolete by standards of glamour in a sweepstake that she of all people had never entered." The personal life was turbulent, with four marriages, several abortions and madness in her family. She said, "My work is all there is. In the final analysis, it's the only thing that never lets me down." By her frankness, and her refusal to mince words, she lasted long enough to trade barbs with David Letterman. Force is what she prided herself on most, enough to put it on her tombstone: "She did it the hard way."

Davis on DVD

Two new box sets fill in gaps in Davis' long career

A COURTIER describing Elizabeth I in 1955's The Virgin Queen: "A woman of both whims and wisdom. The whims are of a moment, and the wisdom will endure after we are dead." Not a bad summing up of the actress who plays the queen in question. The Bette Davis Centenary Celebration Collection (20th Century Fox; six discs; $49.98; to be released April 8), like the title, a bit of a redundancy; it includes gussied-up previous releases like 1964's Hush ... Hush, Sweet Charlotte and 1950's All About Eve.

New to DVD is 1952's Phone Call From a Stranger, which predicts films like Bounce and Fearless. Surviving a plane crash, Gary Merrill (the real-life Mr. Davis) visits the significant others of the demised. Davis, in a part about 15 minutes long, catalyzes the film. She plays a runaway wife whom fate sends back to her marriage; brevity, and director Jean Negulesco's hard-nosed insistence on the strength of true love, forces the melodrama out of this drama.

An extra All About Eve disc has bells and whistles too numerous to mention this week. The Hush ... Hush disc includes an interview with Bruce Dern, who played the suitor who loses both head and hand in the opening scenes of this Southern Gothic thriller. Still, Hush ...Hush Sweet Charlotte deserves its rep as the wheelchair-bound weak sister to What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, with whom it shares cast, director/producer Robert Aldrich and the composer Frank De Vol. (De Vol's spidery title ballad helps the atmosphere immensely). A white, glowing dream sequence, in which the figures are gauze-masked like the Dali figments in Hitchcock's Spellbound, still works. Also credible is the frailty of Davis as a woman frozen in memory of a decades-old horror.

The Nanny (1965), a black-and-white Hammer film, shows how pervasive the spell of Pinter was on '60s English film. Certainly, a corrective was needed after Mary Poppins. Davis is very droll and dry as a tweedy, butch nanny whose little charge (William Dix) can't stand her. The boy's flamboyantly inept parents have their concentration elsewhere, and don't see the trouble brewing. (Davis, eyeing a hangman's noose the boy insists on taking to bed: "Won't that disturb your rest?")

The Virgin Queen (1955) was originally titled Sir Walter Raleigh, though Raleigh (Richard Todd) never sets sail until the end; mostly he's stuck in court, petitioning for a ship to go to the New World. While waiting for a favorable wind, Raleigh has to fight off inappropriate attention from Her Majesty. Davis hijacks the picture, making Cate Blanchett look uncommonly mushy by comparison.

It was Davis' second helping of the part, after The Private Life of Elizabeth and Essex. (Years later, Davis grumbled something to the effect that she'd known Errol Flynn, and Richard Todd was no Errol Flynn.) That aside, it's a large performance for Bette. She uses a sea-captain's walk, and the archaic words roll off her tongue beautifully. Though it's more likely the two performances overlapped, rather than influenced one another, Davis' Elizabeth recalls Olivier's performance as Richard III; she revels in the ruthless delight of being a monarch. With great brio, her Elizabeth wishes her pregnant rival—played by a fast-talking young ingénue named Joan Collins—a serious case of morning sickness.

Warner Home Video also has a new Davis box set, The Bette Davis Collection, Vol. 3, due April 1 (six discs; $59.98). It includes The Old Maid (1939), with Davis, Miriam Hopkins and George Brent; All This, and Heaven Too, a French history romance with Charles Boyer, from 1940; The Great Lie (1941), a romantic triangle with Brent and Mary Astor; In This Our Life (1942), in which Bette steals away Olivia de Havilland's husband, played by the hard-working Brent; Watch on the Rhine (1943), a wartime drama, written by Dashiell Hammett, based on Lillian Hellman's play; and Deception, a 1946 melodrama with Davis caught between Paul Henreid and Claude Rains.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|