home | metro silicon valley index | news | silicon valley | news article

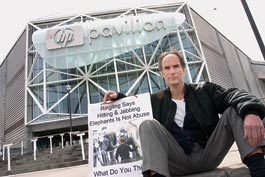

Photograph by Felipe Buitrago

Tempest in HP Lot: Pat Cuviello sits at the spot where he was arrested in 2003. A jury found that HP officials had conspired against Cuviello and two other circus protesters, but cleared San Jose police and the city of any civil rights violations.

The Plot Sickens

The strange but true story of conspiracy with city officials and a secret plan against circus protesters at HP Pavilion

By Sercan Ersoy

IF YOU MET him on the street, you could easily mistake Pat Cuviello for a lunatic, raving about how the management of HP Pavilion conspired with the San Jose city government, and everybody involved was out to get him. It's a rather incredible sounding claim for an essentially unknown Bay Area animal rights activist to make.

Except for one thing: Cuviello proved it.

Cuviello, along with activists Deniz Bolbol and Alfredo Kuba, sued HP Pavilion and San Jose back in January and won, with a jury finding that "an employee of HP Pavilion Management conspire[d] with an official of the City of San Jose to use government authority to restrict the ... free speech activities of the Plaintiffs and then proceeded to take actions which restricted the ... free speech activities of the Plaintiffs."

The whole bizarre story started after Cuviello, Bolbol and Kuba were arrested in the HP Pavilion parking lot while handing out fliers condemning Ringling Brothers for alleged acts of animal abuse when the circus came to San Jose in September of 2003.

The activists were surprised, to say the least, since prior to that their do-gooding had failed to rate any law enforcement attention whatsoever.

"We've been leafleting there since 1993," Cuviello said. "They would call the police, but they were never willing to do anything. I assume they asked them to arrest us, but they never did."

But in 2003 the attitudes of HP's management, particularly the Pavilion's director of Guest Services, Ken Sweezey (who both Bolbol and Cuviello described as being kind and even accommodating in years past), had changed completely.

In the now-notorious incident Sweezey, along with HP Pavilion's booking director Steve Kirsner, confronted the activists almost immediately after they arrived and demanded they leave the premises. When that didn't work, Sweezey placed them all under citizen's arrest and called in police Lt. Trejo to cite them for trespassing.

There is nothing new about activists finding themselves in confrontations with the police, and ultimately the jury decided that simply issuing citations did not prove that the Police Department or the city were part of the conspiracy.

According to San Jose City Attorney Rick Doyle, this was the main reason the city was, unlike HP, cleared of any civil rights violations in the case.

"I think the real issue [regarding the city's involvement] was the police and their actions," Doyle said. "But the jury decided the police acted properly."

According to Sgt. Russ Pacheco—who works off-duty doing security for HP Pavilion—San Jose City Attorney Carl Mitchell only wanted on-duty officers to remove the protesters. "My understanding is I'm off-duty," he said in court. "And this type of an arrest should be handled, to make it as clean as possible, by an on-duty person."

The plaintiffs' lawyer Whitney Leigh says the city was not held liable, in the end, because there is a higher standard of proof required to implicate a government in a conspiracy than it takes for a private organization.

"The judge required that we show the city intended to violate their rights," he said. None of the testimony in court, he says, showed any explicit intent on Mitchell's part to do that.

Bad Planning

But the actions of HP Pavilion management were another story. Especially when it came to Sweezey and Kirsner, who soon after the circus left town found themselves two of the central figures accused of orchestrating and carrying out a conspiracy designed to subvert the first amendment.

Before and after the protest, Sweezey authored a series of emails detailing a new policy for dealing with activists that Kirsner and Mitchell had hammered out. The main point of these emails was the agreement that, on Mitchell's say so, the parking lots would be closed to anyone who did not have a ticket to see the show—a stark change from the mode of dealing with protesters HP Pavilion had followed since they opened in 1993, and a policy that legal precedent had (and has since) said is inconsistent with the First Amendment.

One email even went so far as to say that Sweezey expected "some of the activists will purchase tickets to become guests and then continue to carry out their protest. ... At this point, it is unclear what action we can take to mitigate their activity."

In one bizarre blunder on the part of the defendants, the protesters were cited for trespassing on a day that the parking lot had been expressly opened to the public. According to the Penal Code, trespassing can only occur on land "not open to the general public." Kuba had even been sold a permit to park his van in the lot earlier that day.

A handwritten document outlining a telephone conversation with Carl Mitchell notes that the new policy must be "uniformly applied, announced and enforced" to everyone on the lot, ostensibly for legal reasons. Yet, video evidence the activists shot shows that they were the only ones burdened with compliance while the rest of the public was allowed to roam the area freely.

Even more damning was the fact that the section of the Penal Code they were cited under explicitly states that "this subdivision shall not apply to persons on the premises who are engaging in activities protected by the California or United States Constitution."

When asked about this in court, no one from HP Pavilion could recall Mitchell mentioning the constitutionality of the new policy during the unusual pre-event meeting. Instead the focus was simply on how to keep protesters away from circus patrons.

Sweezey even closed his pre-protest email with the phrase, "as you can see, we are prepared to go the distance to protect our interests." And with all this in mind, the jury found that HP Pavilion had kept people out of a "limited public free speech area which had been opened to the general public as those terms have been defined by the Court," and made them pay $4,800 in damages.

Who Was Behind It?

All of this, though, asks the question, why? From the video evidence detailing the activists' confrontation with Sweezey and Kirsner, and their arrest, it's obvious that no one from HP Pavilion thought they would be able to fight this in court. After 10 years of peaceful animal rights demonstrations, why would the city and HP Pavilion make such drastic changes to their policies in the first place?

According to Sweezey's testimony, Ringling Brothers had expressed concern about animal rights activists operating anywhere near their circuses. "I mean, we had a very key client that we wanted to make sure was taken care of," Sweezey told the court. "So we are doing everything we can to take care of business, to make sure that the promoter and the artist is happy."

Ringling Brothers, after all, is owned by Feld Entertainment, a company that has not only brought the circus to San Jose every year since 1993, but also owns Disney on Ice, a production that comes to HP Pavilion twice a year.

Ringling Brothers had originally been named as a third defendant in the lawsuit—along with HP Pavilion and San Jose—but was dropped early on. However, the idea that Ringling Brothers may be behind Sweezey and Kirsner's attempts to bar people from their venues based on political speech is by no means an isolated one. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) recently completed a lawsuit accusing Kenneth Feld, head of Feld Entertainment, of spearheading a 10-year spying campaign (from 1988 to 1998) against animal rights organizations throughout the country.

According to Jeff Kerr, PETA's general counsel, they had been able to establish in court that the company had engaged in espionage against PETA's national organization along with several smaller groups in California. PETA even admitted a sworn affidavit into evidence from the CIA's former covert operations director Clair George—who was convicted of perjury in 1992 for making false statements to Congress during the 1987 Iran-Contra investigation—stating that he had been hired on to oversee the operations.

Although in the end PETA never managed to prove that Kenneth Feld knew personally what was happening within his company, Kerr seemed pleased with what amounted to a moral victory for the group. "Although the verdict went against us," he told Metro, "we were happy to show the sordid underbelly of the circus, and where people's money is going."

Interestingly enough, HP Pavilion's attorney Frank Ubhaus talks about his own legal defeat with the same optimistic tone. Ubhaus seemed particularly pleased that—since the activists refused to settle out of court—the jury awarded them $5,200 less in the conspiracy suit than HP Pavilion had offered them to drop it entirely.

"There shouldn't have been citizens' arrests," he said, acknowledging HP Pavilion's policies had crossed the line, "[but] as far as we're concerned, we prevailed."

When it was all said and done, HP Pavilion didn't seem too concerned with the conspiracy conviction. When asked if he had any plans to appeal, Ubhaus responded: "Oh God, no!"

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|