home | metro silicon valley index | movies | current reviews | film

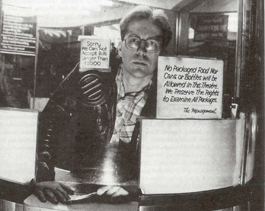

The Booth Is Out There: Michael J. Weldon punches the tickets for horror and cult film lovers.

American Psychotronic

From predicting the new '88 Minutes' to pioneering the pop genre blender, Michael J. Weldon has always been ahead of his time

By Steve Palopoli

SO I WAS flipping through the '90s edition of Michael J. Weldon's Psychotronic Video Guide a couple of weeks ago—it's the kind of book you can pick up and start reading on any page, and I've done so hundreds of times over the years—when I happened across his write-up for the 1988 remake of the film noir classic D.O.A. The end of it read: "Look for the 1949 version. It's 10 times better (and cheaper to buy). This is actually the fourth version of D.O.A. I guess we can expect another version in about 2008."

Something clicked in my head: Hadn't I seen a trailer in the last month or so for a movie that sounded like D.O.A. ? I consulted the Internet—because it knows everything—and sure enough, the Al Pacino film 88 Minutes, which gets a wide release April 18, is basically a remake of D.O.A. : Pacino's "forensic psychiatrist" character has 88 minutes to solve his own murder before he dies.

Considering that Weldon made that call in the early '90s, you have to admit, it's a freaky one. However, with two Psychotronic guides full of thousands of movie reviews, and almost two decades publishing Psychotronic Magazine, Weldon has consistently been one of the most insightful and influential chroniclers of cult, horror and science fiction film. If anyone was going to be correctly predicting movie trends 15 years in advance, the smart money would be on him.

Not that he himself would necessarily think to collect it, which is perhaps the downside of having written so much about so many films for so long. Reached by phone at his home on Chincoteague Island off the coast of Virginia, he admits he has no recollection of that particular review.

.jpg)

© 2008 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. and GH Three LLC All rights reserved.

BEEN THERE, DONE THAT: Al Pacino stars in '88 Minutes,' a

remake of 'D.O.A.,' opening April 18 and proving that Michael J. Weldon

is the Nostradamus of film writers.

"I don't think I made many predictions, but some of them are pretty easy. That's fun that it happened to be the right year," says Weldon. "Guessing that a movie's going to be remade again is not much of a stretch. But the year, that's pretty good."

Oh sure, "happened to be." Look, I'm not one to go around ascribing psychic powers to people who write about Russ Meyer and Doris Wishman films, but as a longtime fan of Psychotronic, this isn't the first time I've noticed some eerily perceptive stuff in Weldon's work. In a sidebar only 17 words long, he once managed to nail almost every trend in Hollywood genre-film formula, from science fiction/horror rip-offs of Alien and Road Warrior to action retreads of Die Hard and The Most Dangerous Game.

"I think it's just from watching so many," says Weldon. "I've slacked off recently. I was intensely watching as many movies as possible for year after year after year, and since I stopped doing my magazine—at least for a while—I've slacked off a bit recently. But they're always there for me to go back and see."

Just how many movies he's seen he'd prefer not to talk about.

"I've watched as many movies as I could since I was a little kid, starting with television, and I was a little kid in the '50s," he says. "I really never tried to calculate it. It's a scary thought. I don't even want to know."

It was in 1979 that Weldon first parlayed his encyclopedic knowledge of film into a writing career—he started out writing reviews for movies that were going to appear on television in Cleveland where he grew up. This was the late '70s, and Weldon's band Mirrors was part of the punk scene that also included Rocket From the Tombs (which split into Stiv Bators' Dead Boys and the famously strange Pere Ubu) and the Electric Eels. Regulars from CBGB's in New York like the Ramones, Patti Smith and Talking Heads were playing his hometown, sometimes before they'd even released a record. The DIY ethic was in bloom.

Weldon worked at a record store where a few guys, led by Pere Ubu lead singer David Thomas, were putting out a punk zine called Cle. Knowing Weldon's love of horror movies, they asked him to write a column for it. When he moved to New York in 1979, he kept the concept, and by 1981 he was putting out the first Xeroxed, hand-lettered copies of his own magazine. For its name, he adopted a word that had previously been used to describe psychiatric studies in the Soviet Union: "psychotronic."

"To me it was a perfect word to make people think of what I mostly was writing about—'psycho' for the horror movies and 'tronic' for the science fiction," he says.

Perhaps the most revolutionary approach Psychotronic took is that, in a complete rejection of film-snob style that was years ahead of its time, it threw out the rigid confines of genre writing. Weldon championed films by Herzog and Buñuel on the same pages that he wrote about the camp horror of Herschell Gordon Lewis and Ed Wood. As for a strict definition of what made a psychotronic movie, Weldon says, "I never exactly had a rule."

That sometimes leads to a misunderstanding about his work among the uninitiated.

"One misconception people have had about what I write about is that it's all bad, or it's all cheap," he says. "I have to point out to those people that that's in no way true. It goes to all extremes, from movies that people made on a camcorder in their back yard and managed to get released to hundred-million-dollar science fiction epics, and everything in between."

The integrity of the psychotronic concept lies instead in a certain non-Hollywood quality that Weldon has sought out from every imaginable source.

"It gets tiring to see predictable retreads, and it's exciting to see something that's different, even if they don't quite pull it off," he says. "Or even if it's really horrible, it can be amazing to watch."

In the end, psychotronic was an idea whose time had come. Though the high cost of printing and paper finally convinced him to give up publishing the magazine a couple of years ago, several dictionaries and the human brain trust known as Wikipedia now use his definition of "psychotronic."

And they're not the only things he's influenced. Psychotronic counted among its fans indie icons like John Waters, the late Johnny Ramone and a once very young and impressionable Quentin Tarantino, back when Weldon ran an East Village cult-film shop with his wife, Mia.

"Tarantino came into the store and he knew about my magazine—which had only been out for a few years then—and he wanted to talk to me," says Weldon.

"I had no idea who he was, but this guy was like a walking encyclopedia of trash culture and movies, and he was fascinating to talk to.

"He came in several times. The second time he came in, he was on the way to the Cannes film festival, and he handed me a VHS copy of Reservoir Dogs. It was a personal dupe, because it hadn't even premiered yet. He wanted to do interviews for Psychotronic. Which maybe he would have done if he didn't become so incredibly successful so fast after that. He did get in touch with me a few times after. I like to think, although he didn't state it exactly, that he cast Lawrence Tierney in that movie after he saw the interview in Psychotronic magazine."

Weldon has considered reviving Psychotronic on the Internet (he maintains both psychotronic.com and psychotronicvideo.com) and hopes to put out an updated edition of the movie guide. Meanwhile he owns a movie memorabilia and vinyl music store on the island, and mixes old radio spots for exploitation movies with rock music at his DJ gig on Saturday nights. He's hesitant to say that he sees the influence of his work on pop culture, but he does allow that the genre-blender that Psychotronic pioneered is now everywhere.

"Sometimes there'd be this debate, 'Well, it's only a horror movie if there's something supernatural. So if there's a monster and it kills all these people and it's scary but it turns out at the end that it's really just a guy with a mask on, then it's not really a horror movie,'" he says. "It was that absurd, you know? I tried to throw away those critic rules about what you can write about."

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|