home | metro silicon valley index | movies | current reviews | dvd review

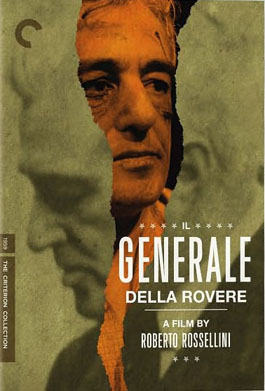

Il Generale Della Rovere

One disc; Criterion; $29.95

By Richard von Busack

Roberto Rossellini's Il Generale Della Rovere (1959) is a film that fits on the shelf between Bresson's A Man Escaped and Renoir's Grand Illusion. In Genoa, at the time of the American invasion at Anzio, Bardone, a silver-haired confidence man (Vittorio De Sica), acts as a liaison between imprisoned partisans and the Germans, when not gambling away his profits. Fate steps in early one morning, when the con man meets an urbane Nazi colonel named Mueller (Hannes Messemer), who figures he can use Bardone in his own struggles against the Italian Resistance. Mueller forces Bardone to go to prison to spy for him, making the con man pose as a distinguished Italian general.

Based on a true story, Rossellini's one other hit besides Open City is, argues scholar Adriano Apra, "autobiographical." The pioneer neorealist director's own struggles to survive during World War II are reflected in Bardone's short cons and strategies. Bardone's redemption fits in with what we've heard about the Resistance—that it wasn't always the noble self-sacrificing characters who made up the organization but also those who had learned how to dodge the cops and authority during peacetime.

As an actor, De Sica reminds one of the solitude and self-amused dignity of late-period Bill Murray, whom De Sica resembles slightly. The calm compositions and sweeping long takes defy not just neorealism itself but the brutally short schedule Rossellini had to finish this film. It was work for hire, and after a long string of flops Rossellini was desperate to be a success. Il General Della Rovere was controversial, but the movie was a success, reconciling dry humor with this play-actor general's growing nobility. "Della Rovere" comes to embody Italy's uniquely ambivalent war history: in which great bravery and real political scheming were hopelessly mixed.

The digitally remastered version of this classic includes a visual essay by Rossellini's biographer Tag Gallagher. (Gallagher suggests that the film's openness about history was partially due to the regime of the reformist Pope John XXIII.) Also included are interviews with Apra and three members of Rossellini's family, in particular daughter Isabella.

Click Here to Talk About Movies at Metro's New Blog

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|