home | metro silicon valley index | movies | current reviews | film review

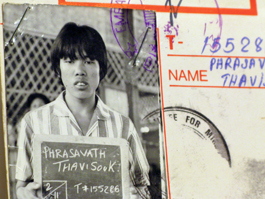

COMING TO AMERICA: Thavisouk Phrasavath's memories about fleeing Laos to the United States inform 'The Betrayal.'

Passages

'The Betrayal' tells the long hard story of how a Laos family came to a new land

By Richard von Busack

THE MODERN STAGE of American/Laotian relations begins with a president who couldn't pronounce the word "Laos." "Lay-ouse," said President Kennedy, was a truly neutral country, "not a Cold War pawn." When the Vietnam War expanded in the late 1960s, the area of Laos that hosted the Ho Chi Minh trail was subject to a savage bombardment; more explosives were dropped there than the tonnage of bombs dropped in World Wars I and II combined. Thavisouk Phrasavath, co-director of The Betrayal with Ellen Kuras, is one of 10 children from Laos, eight of whom made it out. When the Americans left and the communists took over, Phrasavath's military officer father was swallowed up into a re-education camp. His mother was left to tend her vast family herself. "Thavi" escaped over the Mekong, ended up in the streets of Bangkok and finally spent time in a refugee camp. In some respects the worse was yet to come.It turns out that Thavi's father hadn't been killed. For reasons the film reveals, Thavi's father was unready to resume his duties as father when he finally arrived in the United States. Narrated by Thavi and using some 20 years of home movies, this film focuses not on history but on suffering. We observe Thavi's mother's sadness as she learns about the difference between the America she imagined and the America we all know and love: the one where sauve qui peut is as important as e pluribus unum.

"Melting pot" isn't just an expression; layers of culture really do melt away. In home movies, we see the Phrasavath children with the hard stares and teased-up hair of urban New Yorkers, staring down passers-by on the street corner. Eventually, the Phrasavaths were chased out of the city by the Asian auxiliaries of Bloods and Crips—incidentally, some Southeast Asian gangster rap turns up on Betrayal's soundtrack, in which the words "San Jose" stand out. Betrayal has fine dreamy surfaces and fascinating folkloric customs—the divination of the future by dead rooster's claw, the words of ancient prophesies predicting Laos' troubles and the ritual in which a dead man's face is purified with cocoanut milk. That's what the movie has instead of answers. Who were the people who decided it was a good thing to plant nearly two dozen newly arrived refugees in two rooms of a Brooklyn crack house? We get the dreaming land and its fine buffalos but not the actual state of Laos today. Again the film reiterates a mother's pain: her complaints about her children's lack of obedience: "To them, I'm just a crazy person" she says. It's sad to see her loneliness, as she's parked in some far away suburb. But it's also easy to build up resistance to a mother's complaints—as any former child can tell you.

The film's premise is that America stiffed the Laotians it hired as guerrillas, letting them be eaten alive by the ant's nest stirred up by our Cold Warriors. There's little reason to argue with that premise. On a larger scale, the film indicts those who draw up borders, whether politicians or gangsters, whether they wave flags or red and blue rags.

![]() THE BETRAYAL (R; 96 min.), directed and written by Ellen Kuras and Thavisouk Phrasavath, opens March 20 at selected theaters.

THE BETRAYAL (R; 96 min.), directed and written by Ellen Kuras and Thavisouk Phrasavath, opens March 20 at selected theaters.

Click Here to Talk About Movies at Metro's New Blog

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|