home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | books | review

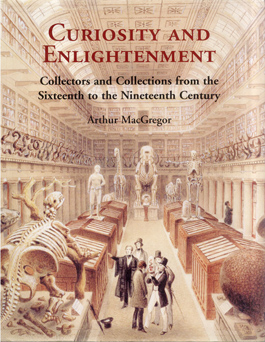

Curiosity and Enlightenment

Collectors and Collections From the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Century

By Michael S. Gant

Visitors to last fall's "Body Worlds" exhibit at the Tech Museum who gaped at Dr. Gunther von Hagens' plastinated human corpses might be interested to learn that such grisly educational displays have their roots in the 17th century. In his endlessly fascinating study of how museums developed, Arthur MacGregor devotes a chapter to some astonishing examples of anatomical models. John Evelyn, the great 17th-century English diarist, commissioned four cedar-plank panels on which the complete dried nervous and circulatory systems of a dissected subject were carefully laid out to form the outline of the deceased, and then varnished to a high gloss. Dutchman Frederik Ruysch (1638–1731) was fond of stage-managing embryonic skeletons and preserved infants in tableaux complete with little mounds strewn with "urinary stones and petrified foliage." Italian artisans crafted extraordinary wax figurines in various stages of disassembly. One specimen, perfectly flayed to expose all the blood vessels, was posed like Adam from the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The instinct for stuffing the dearly departed reached its peak with the "auto-icon" of English philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), whose "resurrected skeleton, rearticulated with copper wire, padded-out and soberly dressed, and surmounted by a waxen head with an ample hat" can still be seen at University College in London; lifting the project from the macabre to the surreal, Bentham's actual mummified head rests on a platter between his auto-icon's feet. This copiously illustrated study traces the growth of the modern museum from the early relic collections of the Catholic Church through the "cabinets of curiosities" assembled by princes and scholars to the large and public institutions like the Louvre and the British Museum that flourished in the 19th century as symbols of Western treasure hunting and cultural triumphalism. MacGregor roams across the European landscape, tracing the forking paths that led from the all-in-one Kunstkammer ("wonder rooms") to the fine-art museum on one hand and the museums of natural science and technology on the other. The text is scholarly without being pedantic, and the illustrations reveal wonderful flights of the curatorial imagination. The eccentric Carl Schildbach, for instance, "encapsulated the entire life-cycle of a huge tree in a small box" constructed from the very materials—bark, sapwood, heartwood, branches, leaves—he wanted to preserve and display. These boxes were assembled to look like "books" and arranged as if on a library shelf—a perfect match, MacGregor writes, of science and metaphor. (By Arthur MacGregor; Yale University Press; 288 pages; $75 hardback)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|