home | metro silicon valley index | features | silicon valley | feature story

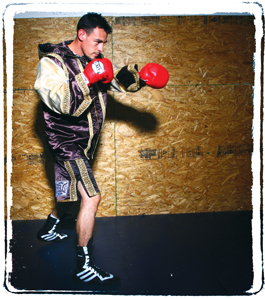

Photograph by Felipe Buitrago

Little Big Man

Robert 'The Ghost' Guerrero is the toughest 130-pounder to ever come out of Gilroy, and he's going to prove it to the world

By Jessica Fromm

ROBERT GUERRERO'S punches echo off his opponent's protective headgear. The boxer moves with confidence, putting together combinations, sliding and pivoting around the ring, driving his sparring partner back against the ropes.

Two steps forward, jab, two steps back. Three steps forward, jab, two steps back. Then a frenzy of lefts and rights, each landing with the deep thump of solid contact. Sprays of sweat pattern the purple canvas around the two men as they duke it out.

Punches erupting in his face, Guerrero's opponent slogs witless through the barrage, heading toward the side of the ring to escape the imminent butchery.

Good boxers need to dance as well as punch, and Guerrero is practically waltzing around this guy, demonstrating superb footwork and agility. Traveling with a decisive, looping looseness, his body is an expression of balanced motion. He carries an elegance and dignity about him—no ordinary wreaker of random carnage, he looks every bit the two-time world IBF Featherweight Champion that he is.

Guerrero points his shoulder toward his opponent at all times, providing the narrowest moving target as he presses forward. He approaches with an arch, an angle where he can hit without being hit, while his less-experienced opponent comes at him full on. He lands another punishing blow. A jab flicks out from his opponent's defensive stance, quaking Guerrero's body. The other fighter is good, but it's obvious that Guerrero is anticipating his moves.

His opponent forgets to keep his hands up for a second, and Guerrero seizes the opportunity. Two more punches explode. Guerrero releases a left, pinning his sparring opponent with an uppercut as he tries to shimmy off the ropes. He drills him with a straight left to the face, then stands back to give the guy some room before the bell rings, indicating the end of the three-minute round.

The fighters stop and embrace each other in a bro hug, fist-bumping gloves and patting each other on the back before dipping under the elasticized ropes. After spitting out their mouthpieces and slipping off their groin protectors, both men sit on the side of the ring as bystanders unlace their 8-ounce gloves.

Once his hands are free, the sparring partner pulls off his protective headgear. Soaked in sweat and still shiny from the Vaseline smeared around his eyes, nose, cheeks and lips before the fight, Randy Guerrero, Robert's 17-year-old brother, is panting with exhaustion. But then he smiles, intoxicated from the beating inflicted on him by his older brother, a double dose of endorphins and epinephrine flooding his body.

Though it looked like a tough match, Robert later says he went easy on his little brother. This was just a friendly sparring session at Robert's newly opened boxing gym in his hometown of Gilroy. Robert could have hit him harder. Much harder.

FIGHT CLUB: Robert Guerrero and his after-school students at the Ghost Guerrero Boxing and Fitness Club in Gilroy; the graffiti mural behind them reads 'The Ghost.'

Pride of Gilroy

Robert "The Ghost" Guerrero possesses a serious knockout punch, a talent the southpaw has proven in the professional ring 16 times. He could have taken on three or four more guys that night, the way he does when he is training hard-core, as he is right now, in preparation for his next big fight, June 12 at the HP Pavilion. Guerrero (23-1-1, 16 KOs) will be returning to the Shark Tank next week in the main event of ESPN's televised Friday Night Fights against North Carolinian Johnnie Edwards (15-4-1, 8 KOs).

Guerrero is the pride of Gilroy, the town where his family has lived for three generations. Pugilism is a way of life for the Guerrero clan. His grandfather boxed professionally in Texas; his father, who is now his trainer, was an amateur champion. His uncles boxed; his five brothers box.

At 5-foot-8 and 130 pounds, Robert is shorter in stature, lighter in complexion and slighter in build than any of his burly brothers. Though he is ripped from his intense training regiment and strict diet, he is still a junior lightweight. A decisive, thoughtful speaker, Robert has a light behind his eyes not common in the boxing world, a profession spent getting hit in the head.

Some small men are apt to be a bit disputatious and peppery, but Guerrero has an extremely humble, almost shy manner. That is in stark contrast with the animal he becomes in the ring.

"Nobody expected me to get this far," Robert says. "They expected my two older brothers to do big things in boxing, and here comes me. They were amazed, like 'Wow, that's the least likely guy we thought was going to do it.'"

Robert is the fourth in a family of six brothers. His father, Ruben Guerrero Sr., got his sons into boxing to stop the constant melee that resulted from so much testosterone in the house.

"My older brothers boxed, my father was a fighter and my grandfather was too, so I was basically raised around boxing," Robert says. "As soon as I was old enough, I just couldn't wait to get in. As soon as my dad signed me up, it just took off from there."

Guerrero's first gym was at a dairy farm. He later moved into town, to a gym off Sixth and Railroad streets, and has been fighting out of Gilroy ever since. Robert's older brother, Ruben Guerrero Jr., who now runs the Ghost Guerrero Boxing and Fitness Club in downtown Gilroy, says that when he was growing up, nobody expected Robert to be the successful fighter in the family.

"Honestly, no," says Ruben, who had some success as an amateur fighter in his teens and resembles more his father's sturdy physique and easy-talking demeanor. "He just hung out on the ropes and watched us work out, and watched us fight."

Ruben says that Robert has worked hard to stay on the straight and narrow, something that isn't always so easy in a town like Gilroy.

"He knows where he came from, and he worked hard and stayed focused. And he's learned off of his older brothers' mistakes," says Ruben Jr. "I lived the party life; I loved to go out. I was big-time, boxing time, but I partied. Another brother had kids. Another brother went to prison. We were all fighters, and we could all make it, but he was the guy that said, 'Hey, I'm not going to do that.' He learned from our mistakes."

Robert earned the nickname "The Ghost" in his earliest days of boxing.

"When he was a young kid, he was so quick and little, he looked like a little lightning guy," says Ruben Sr. A two-time Golden Glove champ himself, Ruben Sr. now works as Robert's trainer and motivator. Shorter and stockier then his son, Ruben Sr.'s thick goatee is flecked with gray, a deep furrow permanently etched between two fuzzy eyebrows. "The other kids couldn't see him, they'd just turn around looking for him, and Robert would just throw punches from nowhere. They were like, 'Man, you move like a ghost, we can't hit you. You're here, and then you not there; you disappear.'"

Ruben Sr. says his youngest son's work ethic and passion for the sport set him apart from his brothers.

"The talent is already there, so the only thing I recognized is that he really wanted it," he says. "It's all Robert's doing, because he wanted it."

Robert Guerrero won his first national tournament at the age of 15, competed in the national Junior Olympics and then went on to qualify for the 2000 Olympic trials, where he took third place. He was one of the youngest fighters to ever compete in the Olympic boxing trials. He decided to turn professional right out of high school, at the age of 18.

Though Guerrero has been boxing in the big leagues for eight years now, he still possesses the delicate features of a young man. His eyebrows are not yet hooded by the scarred and swollen flesh indicative of veteran boxers. Still, clusters of thin, pale scars are barely noticeable through his eyebrows. The most visible scar sits above his right eye, an injury inflicted on him last March by a head butt in the second round of his first HP Pavilion fight—a blow that marred his reputation more than it did his face.

THREE GENERATIONS IN THE RING: Left to right) Robert Guerrero, his father Ruben Guerrero Sr. and his grandfather Robert Guerrero Sr.

Complete Athlete

From an outsider's view, boxing can seem like a relatively easy thing to do if one is thick enough. Even after great, intelligent fighters like Jack Johnson, Muhammad Ali and Marvin Hagler, popular culture still holds onto the stereotype that boxers are more brute than human. A boxing match is seen in some corners as a brawl with padded gloves rather then a sport, and fighters themselves as a jumble of impulse and viciousness.

Truthfully, a professional fighter has to be both a sadist and a masochist to like what he does. Most people don't enjoy getting punched in the face, and when they do, most have a logical reaction: "This is bullshit! What the hell am I doing? I'm getting out of here."

Robert Guerrero has been passionate about boxing from day one. "There was no doubt in my mind, it's what I wanted to do," he says. "I love boxing so much, I wanted to do it for a living. Not many people get to do what they want."

The truth is, the cliché applied to boxers is often far from the reality. Professional fighters have to be more complete athletes to do what they do than participants in virtually any other sport. A great fighter is able to maintain his reasoning when instinct, pain and adrenalin are blurring his mind.

Every single day in the months that lead up to a big fight, Robert gets up at the crack of dawn to go on a nine-mile run, his father training and pushing him all the way.

"His dad shows up at my house at 5am honking and flashing his lights, and he'll knock on the door. That's when he'll get up and go running," says Casey Guerrero, Robert's wife, in an annoyed tone.

Casey sits curled up in a chair in a small office located at the back of the gym. When not in the hospital, she comes here a couple times a week to help out with paperwork and the business end of the fitness center. Though proud of her husband's success in the ring, Casey herself has been waging her own internal battle with serious illness.

The gym is clammy and warm, but Casey's painfully thin frame is clad in a pair of minute skinny-jeans and a parka, a white-knit brimmed beanie on her head. Her makeup is impeccable, foundation and blush applied expertly to give her sunken cheeks color, flawlessly painted black eyeliner rimming her lashless eyes, the perfect arching of her eyebrows made out of pencil. Without really eating, she picks at the potato wedges and array of fast food laid out in front of her on the office desk.

"That's why he has his dad," she says. "To push him to do all that, or else he would probably lie in bed till 10am and then go do it."

When Robert gets home from his run, he eats a simple, lean, salt-free breakfast, plays with his two kids, 4-year-old Savannah Rose and 2-year-old Robert Jr., kisses Casey goodbye, then heads off to the gym to train with his dad.

In the late afternoon, he'll hang around helping out with the 60-plus children and teenagers that flood the small gym after school to work out and learn to box.

The Toughest Fight

Robert Guerrero is a nice guy. He's a family man, a respectful and genuine hometown hero. But with all the community outreach and squishy feelings he inspires in his Bay Area fans, one question hovers around the edges of his career: Is he tough enough to be a champion again?

After a series of personal and professional setbacks, many in the boxing community are wondering if Guerrero is still the gritty fighter he used to be.

The fact of the matter is, Guerrero has been doing more fighting outside the ring than in these last two years, his opponent a hundred times more lethal then anyone he has ever faced between the ropes.

Robert and Casey met when they were 14. They became high school sweethearts and were married four years ago. Two years later, in 2007, shortly after giving birth to Robert Jr., Casey was diagnosed with leukemia.

Robert was one week away from a title defense in Arizona against Martin Honorio (24-3-1, 13 KOs) when he got the news. He knocked out Honorio in 56 seconds in that fight, then immediately flew home to be with his family.

"He takes me to my doctor's appointments, check-ups. Everything that I have to go through, he's with me," says Casey.

Then, another blow. Following an eighth-round knockout victory against the previously unbeaten Jason Litzau in February 2008, a fight that won Guerrero national attention because it was aired on Showtime, the young fighter was forced into a 10-month layoff while in litigation with his former promoters, L.A.-based Goossen-Tutor. He was stuck in arbitration for almost a year over the contract dispute.

"I was going crazy not being able to fight, just training and being ready and then getting in a suit and going to court," Guerrero recalls. "It was frustrating, just coming off of two excellent fights on Showtime, two back-to-back exciting knockouts where the media was excited, everybody in boxing was excited. And then, nothing for a year. So, it was a tough situation."

As soon as he got out of the contract, Robert signed with Oscar de la Hoya's Golden Boy Promotions Inc. He then abdicated his IBF title, moving up from 126 pounds to the 130-pound division.

And then came another hit. Casey's leukemia, which had been in remission for over a year, recurred in January.

Rules of Boxing

Every boxer knows that he is only as good as his last fight. Guerrero has a lot to prove with his June 12 match, both that he can carry a major arena boxing card and that he can still win. Though it was not a loss, Guerrero's last bout was particularly disappointing.

The fight was aired on HBO's Boxing After Dark live from San Jose on March 7. More than 7,000 Bay Area fans had crowded the Shark Tank to watch Guerrero battle undefeated Indonesian fighter Daud Yordan (23-0-0, 17 KOs).

The heavily pro-Guerrero crowd cheered on their hometown favorite as the fight began. Yordan took the initial round with several right-hand combinations to Guerrero's head. But it wasn't until the second round that the trouble began. Yordan attempted to clinch Guerrero, but instead the men butted heads, opening up a deep gash above Guerrero's right eye.

Blood mist clouded Guerrero's vision as he gunned it out with Yordan, slinging punches as hard has he could. With Guerrero unable to see, the referee stopped the fight at 1:47 in Round 2.

Misinterpreting the early stoppage as an indication that Guerrero had lost, the large Shark Tank crowd began to boo when the fighters were pulled apart. The fight was ruled a "No Decision by Accidental Head Butt" because it had only lasted two rounds, in accordance with the California Rules of Boxing. Yordan was up slightly in the scorecards when the fight was stopped.

With blood pouring from his eye, Guerrero did not dispute the decision. That's a fact he now regrets.

"The doctor stopped the fight," he says. "I'm not going to argue. Now, when I look back, I wish I did argue," Guerrero says. "That's where I got most of the criticism, because I didn't protest the stoppage. Even if I did protest, they still would have stopped it anyway. But that's what the fans love to see."

Boxing fans and critics were disappointed in the March 7 fight, many complaining that Guerrero gave up too quickly and didn't show enough tenacity in the ring. There have even been rumblings that Guerrero's quick acceptance of the no-decision has put him on HBO's shit list for the time being, for delivering such a short televised performance.

"It's one of the most brutal sports in the world," Guerrero says, "and that's what they like, that rugged tough guy. But, hey, if they make the decision, they make the decision.

"Still, I wish I would have protested, but I'm not that type of guy. I'm here to shine light in on the sport, not make it look bad. I'm not going to get out of control and up in people's faces."

Guerrero's camp has challenged Yordan to a rematch, but the Indonesian fighter has turned it down, a fact that they interpret as proof that he's afraid to face Guerrero again.

According to Ruben Guerrero Sr., there was a reason that Robert might not have been on his A-game the night of the Yordan fight. The day before the match, Robert and his wife found out from the doctors that she might need a bone-marrow transplant.

"They don't know what Robert's going through," his father says. "They don't know that Robert's wife just went into the hospital. They told him that the day before the fight.

"I could tell, that's not my Robert. His mind wasn't here. It was back with his wife and his kids. But now, it's better now."

Giving Back

The Guerrero family never had things easy. Growing up in Gilroy, Robert and his brothers frequently worked in the South County agricultural fields to help make ends meet.

It was this connection to the Gilroy community that spurred Guerrero to open up his own boxing gym last March, a place for him to train and his family to work, and a way to give back to his hometown. "The boxing program in Gilroy that I grew up under got closed down, you know, there wasn't enough funding," Guerrero says.

Over the last few years, South County has seen a sharp spike in gang violence, and Guerrero says it was important to offer kids a place to go after school where they could be supervised, have some fun and get some exercise too.

Though it's been less then four months since it opened, a salty mist already permeates the Ghost Guerrero Boxing and Fitness Club, along with the smell of sweat and glove leather.

The small gym's mirrored walls knit the space together. On most afternoons, older teens and adults hang out in groups along the perimeters, shadowboxing, lifting lightweights, doing the slip-slap cadence of jumping rope, heavy punching bags creaking on chains as they get battered. As Guerrero walks around his crowded gym, the younger kids watch him in awe.

"I teach them the basics of boxing, hard work ethic, basically working on their character," he says. "It takes a lot to be a fighter, a lot of discipline, so, they see that out of me. I say, 'Look, I don't look like a fighter, and look what I'm doing.' It inspires them."

Robert has an easy way with the younger kids, talking and joking with them casually, animated and grinning as he mimes a punch.

"He always talks to the little ones," says Hector Catano, a family friend who has been leading classes at the gym since it opened. "I tell them, 'I knew him when I was your age,' and they ask me, 'Can we be like him?' and I tell them if they put their heart into it, then yeah."

You can see their excitement as Robert encourages them and shows them pointers.

"He teaches us, like, the footwork, and how to do uppercuts and stuff," says 14-year-old Aaron Avena, showing off an enthusiastic if not totally balanced combination. When asked what the most fun thing is that he's learned so far, Avena doesn't miss a beat. "Sparring!" he exclaims. "I get to sock people without getting in trouble."

Guerrero and his family take pride in the fact that many of the kids that attend their gym come from a tough background, like Guerrero and his brothers did in their youth.

"I've got three kids that come in from working out in the fields all day," says Ruben Jr. "They get home-schooled so they can help their parents in the field and working at a fruit stand. So this is their playtime now, right here. These kids are a big inspiration for me, because this is how we grew up, me and Robert. And here they are in the gym, just like us. They want it, they love it, they soak it up.

"We got kids off the street who were gangbanging, smoking weed. They get inside the ring and they tear it up. They get their aggression out, and when they go home, they sleep, they do their homework and they can't wait to get back in the gym."

Sparring Sense

The sparring ring is the psychic center of a boxing gym. Boxers fight. To prepare to fight, boxers must spar. A real fighter can't wait to get into the ring.

Its time for the show to begin, and Ruben Sr. agrees to let two eager teenage boys suit up to spar. The teens shimmy into their groin protectors, slip in their mouthpieces, pull padded headgear over their ears and have their gauze-wrapped hands tied into the leather boxing gloves.

This is what they came for: to hit each other. Everybody in the gym halts their workouts to stop and watch, gathering around the ring's ropes to see these two young men duke it out.

Robert and his dad each man a corner, and from the exhilaration on their faces, it's obvious they both thrive on the threshold of real combat. When the bell rings, the two skinny boys rush toward one another, punching wildly. Standing with their arms on the ropes on either corner of the ring, the Guerreros holler instructions to their padded little warriors.

"Keep your head up."

"Get more busy, Aaron."

"Stick your jab."

"Don't hit the back of the head, just the face."

"Come on, Tony, he's tired."

Bystanders can see the young, inexperienced men in the ring faltering between anger and fear. Sweat dribbles from their pores, the tension pressing and binding as one boy, beginning to show dominance in the second round, lands a few solid punches.

Enraged at the punishment and wanting to hurt back, the opponent lunges after the dominant kid in frustration. But, with his head down, mouthpiece bulging from his lips, every wild miss slews the kid off balance.

At the beginning of the third round, the dominant teen throws an elbow to his opponent's head by mistake, sending the young man to the canvas.

Robert and his dad rush in, and call off the sparring match. The teen stands up, then dips under the ropes and jumps to the side of the ring where they untie his gloves. The reddened face underneath his headgear betrays that he's holding back tears. He separates himself from the group and walks a few paces away from the ring. As he halfheartedly hits a punching bag, it's clear that the young man's pride is more hurt than his body. Then Guerrero walks over to talk to him.

"I just told him, 'Look what happened to me,'" Guerrero says later. "'I got head-butted in front of all of my fans in Gilroy and San Jose, I got head butted and wasn't able to fight.' I said, 'Don't worry about it, you ran into an elbow, just sit out a little bit and recover.'

"We're going to get him ice, now. He's got to recharge, he got a little bit dazed. That's the thing, it's a boxing gym, and so all the kids have egos."

A Beast

Currently in remission again, Casey is doing much better. She will continue to receive chemotherapy for another year. But for the first time since his wife was diagnosed with cancer, Robert felt comfortable enough to fly to Los Angeles at the beginning of May to train intensely for his June 12 fight.

"She's doing great," he says. "That has been the most tough fight I have ever been in, just watching her fight her fight. But she's doing real good now, and I thank God that she's on it, and she's getting healthy."

Professional boxers spend over a month before a big fight at what is referred to as "camp," focusing solely on preparing for the match, and sparring with other world-class fighters. They hit up all the big boxing gyms, working out, eating right and resting up for the big day.

"L.A., that's where the tough guys are at," Ruben Sr. says. "At those kinds of gyms, if one guy don't cut it, we'll just put in another guy. Robert usually goes through three, four guys when sparring. They get hurt and jump out, so they get fresh guys to jump in, three, four rounds with each guy.

"They can't handle more then that with Robert. He's a beast, man, Robert, when he's on his A-game all the time."

As this story goes to print, Guerrero will be at the peak of his training, having spent five weeks in L.A. working out and sparring with other pros at world-class gyms, like Freddie Roach's Wild Card Boxing Club in Hollywood, the gym Manny Pacquiao trained at for his victorious match over Ricky Hatton on May 2. (Robert's money was on Pacquiao that fight. He makes sure to catch every match, viewing the Filipino fighter as his future competition.)

Though Johnnie Edwards isn't an ideal opponent for Guerrero to get HBO's attention with again (Edwards has lost three of his past five fights), another win may serve as a jumping off point for a junior-lightweight title shot in August.

Two days before leaving for camp in Los Angeles, Guerrero expressed excitement about the upcoming fight, and disappointment in the negative way many of his fans reacted to his last match.

Sitting in Sue's Coffee Roasting Company in downtown Gilroy on a rainy Friday evening, Robert wears Adidas, gym shorts and a huge oversize hooded sweatshirt with "Team Guerrero" scrawled on the front in red letters. Guerrero's massive sweatshirt comes down past his groin, practically swallowing him up when he sits, making him look more slight and boyish then ever.

"Boxing is a weird sport, the fans, the promoters, the TV networks," Guerrero says. "It's mind-boggling the way they work.

"My last 16 fights, I knocked out about 14 guys, and they were exciting knockouts, where the guys are barely getting up, and they were beat up bad. I get a cut, the fight gets stopped, and everybody is like, 'Wow, what happened?' I guess it's because they are so used to seeing me so dominant, that if anything else happens, they are befuddled.

"The fight before this last fight, I knocked the guy out 42 seconds in. I knocked him out, body shot, he couldn't get up. The guy before that, I just destroyed the guy. It was like a massacre, it looked like the guy had run into a chain saw, and he couldn't go on anymore. The fight before that, I knocked the guy out, 56 seconds with the first shot I hit him with, out cold. And one little thing goes wrong. ..."

Guerrero pauses and thinks before completing his sentence.

"But that's the way boxing is, and I just have to fight my way out of the corner. It's exciting, though, because now I've got something else to prove."

"This little cut, they did a great job stitching it up, and on June 12, I'll be back. I can't wait. They're going to get what they love to see. No more Mr. Nice Guy. No more Mr. Soft Guy. I just can't wait to put on a show for everybody."

As he gets up and walks toward the coffeehouse door, another customer comes in and recognizes him. "Hey, watched your last fight," the local says. Robert smiles and waves goodbye, slipping on his hood and heading across the street to Garlic City Billiards for a round of pool, just like any other local kid.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|