home | metro silicon valley index | movies | current reviews | film review

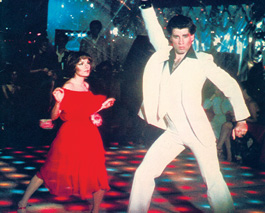

Dance Fever: John Travolta took a working-man's night out and made it into a velvet-rope craze in 1977.

Inconstant Mook

Has it really been 30 years? San Jose's Cinema San Pedro brings back the disco strut of 'Saturday Night Fever.'

By Richard von Busack

EVERYONE KNOWS the pose: the white suit, the tapered black polyester shirt, the right arm thrust up toward the rim of a mirrored ball. Diffused colored lights gleam through the Perspex floor below him. Next to him, two-thirds his size and seemingly 10 feet away, is his dance partner, immaterial to his glory.

Thirty years ago, a British journalist named Nik Cohn published a June 7, 1976, New York magazine article titled "Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night." Decades later, Cohn had to admit that he had pulled the story of a dancing king right out of his fundamental aperture: "I made a lousy interviewer," he told New York. "I knew nothing about this world, and it showed. Quite literally, I didn't speak the language."

Cohn's confession of a hoax was too late to retrieve the article's 1977 film adaptation, Saturday Night Fever. For two years, disco shook popular culture, until the backlash began and the mass burning of disco records in 1979 at Comiskey Park in Chicago.

Saturday Night Fever—which shows next Wednesday, June 21, at Cinema San Pedro—is a piece from a leaner, more serious age of filmmaking. What's forgotten is the abrasive script by the manic-depressive eccentric Norman Wexler; what's remembered are the dry-ice clouds swirling around the dancers' feet and the long dance to "More Than a Woman" between Travolta and Stephanie (Karen Lynn Gorney), the girl with uptown dreams.

Still, the film isn't even as redemption-packed as Hustle & Flow. Saturday Night Fever has far more in common with Mean Streets than, say, Thank God It's Friday or even Saturday Night Fever's putrid sequel, Staying Alive.

Travolta's vulnerable adolescent Tony is a product of his Bay Ridge environment. Son of an unemployed construction worker, he's trying not to get married too early. Annette (Donna Pescow), a zaftig neighborhood girl, clings to him, but he has no plans. ("Fuck da future.") Walled up with a large and squabbling family, Tony is only really at home in front of his bedroom mirror. He and his posse of poly-substance-abusing mooks live for the nights when they can head for the 2001 Odyssey disco, to banter with the women.

You can always tell a true film sex symbol by the wrath he triggers in some men. In his heyday, the star of Saturday Night Fever, with his fine feathers, his pompadour and his lush pout, was familiarly referred to as "John Revolta." Randy Newman may have gotten the ugliest, in his potshot song "Pretty Boy," where he poses as a thug about to stomp a Travolta type: "That dancing wop in those movies. ... How 'bout it, ya little prick? How 'bout it?"

Critics argue that disco backlash was an echo of prejudice, that white boys shuddered at the brothers Gibb because their music sounded black. Some argued that hating disco was an acceptable way to vent homophobia: it was gay to enjoy dancing. (In light of the scene of Tony's pals fag-baiting passers-by, note that the real-life 2001 Odyssey at 802 64th St. in Bay Ridge later became the Spectrum, a gay club.)

But there were two other reasons disco faced such a backlash. Firstly, disco was dance music and had a license to be lyrically stupid, compared to Dylan, Joni Mitchell or even Led Zeppelin. (Cryptic stuff in there, about the bustle in your hedgerows.) The second reason for the revolt was more personal: disco looked like it would cost money. Say what you will about the 1970s counterculture, but they did adopt Thoreau's maxim, "Beware of any enterprise requiring new clothes."

If some of the disco loathers had actually bothered to see Saturday Night Fever instead of spitting every time they saw the poster, they would have learned it concerns lower-class kids who work at hardware stores and drive cars with doors that don't match. The film shakes off snobbery, like a bad dream. Tony finally escapes the narrow-mindedness of his neighborhood and leaves his disco, a cockpit of prejudices.

How could such a poor-man's film have spawned the velvet rope, the dress code and the $7.50 cocktail? When the smoke of burning records cleared, disco triumphed. It morphed, it spread and it nearly killed off live music. What's left is the film itself, showing for free next Wednesday.

Watching Tony, carrying the beat of the Bee Gees' songbook in his every step, the pathetic Annette says, "I wanted to watch you come down the street. I like the way you walk." The movie has lines like that, underplayed, unhyped; there are moments that have the awkward charm of a Jonathan Richman ballad.

Travolta squandered his star-making performance by taking up a series of zeitgeist action figures: gym man (Perfect), cowboy man (Urban Cowboy), '50s guy (Grease) and gigolo (Moment by Moment, maybe worse than Battlefield Earth). It's no wonder that audiences began to think of him as a male Barbie, until a typically perceptive Quentin Tarantino put him back to work. In Saturday Night Fever, the clothes and the music may be dated. But here, Travolta is every adolescent's dream of how he wants to be seen.

![]() Saturday Night Fever shows Wednesday, June 21, at dusk at San Pedro Square in San Jose as part of Cinema San Pedro, sponsored by Cinequest. Free, bring your own chair. (See www.cinequest.org for details.)

Saturday Night Fever shows Wednesday, June 21, at dusk at San Pedro Square in San Jose as part of Cinema San Pedro, sponsored by Cinequest. Free, bring your own chair. (See www.cinequest.org for details.)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|