home | metro silicon valley index | columns | Wine

Terroir Alert

By Christina Waters

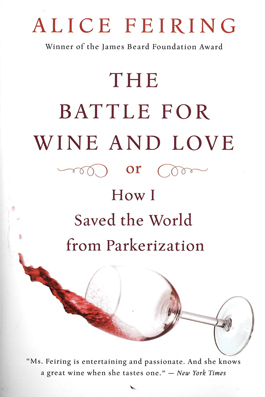

ALICE FEIRING is upset about terroir. Or rather its absence. And her new book, The Battle for Wine and Love, or How I Saved the World From Parkerization (2008, Mariner Press; 288 pages; $13.95 paper), is a sassy riff on Feiring's dismay with winemaking tricks—especially in California, and especially since the dawn of the numerical ranking system popularized by Robert Parker Jr. in the mid-1980s.

Terroir, a tongue-bending French term for the unique space/time signature of a vineyard, is certainly the reigning buzzword in wine circles. Everybody uses the term, but few winemakers have the cojones to actually allow its natural expression. As Feiring sees it, terroir is most evident as an absence, a ghost that haunts the big, jammy, over-oaked, malolacticized, micro-oxygenated wines cranked out in the New World.

Why are these "fruit bombs" made? Because they're immediately drinkable. Because they're rich and fat with flavor—think Hawaiian punch with high alcohol—and because Robert Parker Jr., the shaman of wine desirability, bestows his influential imprimatur (90-plus points) on wines that are big in fruit, thick in texture and rich as syrup. Given the high financial stakes of the expanding market for Big Wine, others have rushed to do the same. Once Parker's ratings became the Big Wine gold standard, the "paradigm of a great wine shifted to one big, jammy, oaky fruit bomb and the whole industry adjusted accordingly," Feiring complains.

On her literary way to wine wisdom, through tireless and charmingly annotated tasting, Feiring noticed the vapidity and sameness of wines made in California, mostly by graduates of the hallowed UC-Davis oenology program. Compared to the nuanced minerality of so many French wines, California oeno-entrepreneurs produced confections that blew away both the palate and the pocketbook. So, as her readable pages recount, Feiring set out to ask winemakers and educators just what the hell was happening.

She learned about oak and yeast, the two big gateway drugs to winemaking abuse. Small, new oak barrels yielded wines whose native origins—that terroir that everybody said they really and truly wanted—were obliterated by aromas and flavors of vanilla, toast, coffee and butter. More Betty Crocker than Romanée-Conti. And who knew that today's designer yeasts produce such flavors-on-demand such as strawberry, cocoa and cherry? We learn about tannin additives and reverse osmosis to reduce alcohol, and behind-the-scenes lore about additives, enzymes and acids. By Chapter 4, I felt queasy about how much manipulation wines endure just to gratify the unsophisticated public.

When Feiring begins her chatty meetings with European winemakers, eating, cavorting and tasting, she begins to lose me. By the penultimate chapter—a long, self-serving and bitter "interview" with the villain of her book, Parker himself—Feiring has lost the coherent threads of her argument. Nonetheless, the book's richness of wine lore and revelation, even if you don't agree with her purist condemnation of "jammy fruit bombs," make it an absorbing read.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|