home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | visual arts | review

Collection of Mark Parker

SCHORR LINES: Cartoon surrealist Todd Schorr rifles through the catalog of American pop imagery with old-master skill

Consumer Gods

Todd Schorr's 'Hydra of Madison Avenue' roils with images from the history of American advertising.

By Michael S. Gant

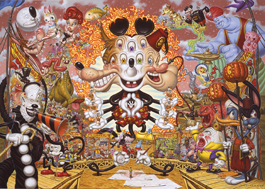

EVERY AGE gets the gods and devils it deserves. The pantheistic ancient Greeks and Romans populated their pantheon with lightning-bolt-wielding Zeus and dog-walking Artemis. The Christian Middle Ages quaked before pits of hell full of fallen angels and demons based on the seven deadly sins. In the jumbled-up mythos of L.A. artist Todd Schorr, now generously displayed at the San Jose Museum of Art, late-period capitalists pay homage to consumerist icons like Speedy Alka Seltzer, Elsie the Cow and the Jolly Green Giant. The whole prep-walk of modern advertising spokesgods make an appearance in Schorr's mammoth The Hydra of Madison Avenue (2001, acrylic on canvas).

The major deities—Bob's Big Boy, Mr. Softee, even the fire-breathing god of PSAs: Smokey the Bear—rise on the multiple necks of a rampaging dinosaur (possibly Gertie of early animation fame). A multitude of lesser supernaturals surround them: the White Rock fairy, the Kool-Aid pitcher, Chiquita banana, Reddy Kilowatt, Mr. Clean, even the triumvirate of the Pep Boys. They cascade through a Boschean landscape, merrily headed for some apocalyptic collapse of buying power.

Collection of Elizabeth Wang-Lee and Oliver Hengst

The Deviled Egg (2000, acrylic on canvas)

The dazzling range of Schorr's pop-culture references is matched by his exceptional ability to bring classic painting techniques and tropes to bear on our love/hate relationship with the avatars of kitsch. In the upper-right corner of The Hydra, for instance, we see a heavy purple curtain being pulled aside to reveal the scene as a jaunty Mr. Peanut directs our attention to the spectacle, a common frame-within-a-frame device. His Parade of the Damned (2006) is explicitly based on a monumental Bruegel painting.

Schorr, a baby boomer born in 1954, omnivorously collects pop imagery, from ad logos and pulp magazine covers to Saturday-matinee stills and the Rat Fink of Ed "Big Daddy" Ed Roth. Vintage Mad Magazine artists loom large as well, especially the grotesque, teeth-baring, pockmarked heads of Basil Wolverton. At times, the frenzied activity of Schorr's larger canvases recalls the epic two-page spreads of underground '60s cartoonist S. Clay Wilson. King Kong, an early indelible cinematic memory, figures prominently in several paintings. The most astounding of these is Ape Worship (2008), a wall-filling tribute to a youngster's fascination with the tragic ape. The prone kid in the foreground absorbed in an old TV set broadcasting Kong is Schorr himself. The whole of the Kong legend unfolds as cartoon, carnival banner, magic show and jungle diorama. The illusionist details are neatly contrasted to the fabulous subject matter. In many grandiose 19th-century landscapes, a tiny figure of an artist's artwork can be seen in the foreground; this time, it's an ape skeleton in a red cap holding a palette: Kong regarding his own creation myth. Schorr has even fashioned a massive frame complete with shields and chains. "Look at Kong, the Eighth Wonder of the World," to quote Carl Denham.

Collection of Mark Parker, Oregon

The Spectre of Cartoon Appeal (2000, acrylic on canvas)

Schorr shows off all his painterly skills in Five O'Clock Shadows in Disney-Dali Land (1996), which depicts an imagined meeting of two great image makers. Walt with Mickey Mouse ears stares into the eyes of a giant melting Salvador Dali, his worm body supported by rickety wooden crutches. Walt looks lighter on his toy-spring feet, but the Sal's mustache is bigger. Call it a draw. The painting is Schorr's acceptance of the label so often given to him of "pop surrealist."

Picking out Schorr's pictorial influences is fun, like taking a graduate-level trivia course. After a while, however, such visual overload, so glossily perfect in execution, can be wearying. I found myself drawn to some anomalous works on view. A couple of exquisite, jewel-toned miniatures focus tightly on a malevolent Halloween pumpkin head beast. Under Autumn's Tentacled Spell (2008–09), for instance, has the impact of a Redon.

Perhaps most interesting of all is a large banner from the 1940s by circus artist Fred Johnson used to entice carnival-goers to ogle the Turtle Boy, a sideshow attraction with no hands or feet. This magnificent example of a lost genre is meant to illustrate one of Schorr's many sources. Curiously, Johnson's Turtle Boy, crawling through a swamp, turns to regard us with a completely sympathetic, utterly human gaze. Not once in all of Schorr's paintings do we encounter such empathy.

TODD SCHORR: AMERICAN SURREAL runs through Sept. 13 at the San Jose Museum of Art, 110 S. First St., San Jose. (408.271.6840)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|