home | metro silicon valley index | movies | current reviews | dvd review

The Soft Skin

Godard anticipates deconstruction in 1964 equilateral love triangle 'Une femme mariée'

By Richard von Busack

TWENTY-THREE-YEAR-OLD Mme. Charlotte Giraud (the almond-eyed actress Macha Méril) has, for three months, been the mistress of an classical theater actor named Robert (Bernard Noël). She is the wife of a private pilot named Pierre (Philippe Leroy), a man 10 years older than she. He has been previously married and has a son from his first marriage who looks at Charlotte as if she were his mother. Such is the triangle in Jean-Luc Godard's 1964 Une femme mariée (a.k.a. A Married Woman), newly available on DVD.

The film begins with the playful seizing of Charlotte's wrist, set against a white paper background; it ends with a male hand relinquishing the grasp. Here are characters literally on paper, paper-lovers. When writing the script, Godard's gambit was to correspond with Elle magazine's advice column to ask whether a straying wife should return to her husband or go off with her new lover. Charlotte comes to us in sections: a flat torso that fills the screen, the finely shaved legs, the nude shoulders and back. She's a woman in pieces, shielded in fade-outs, calmly bathing, changing clothes, shuttling between the two men. One is her dull husband: a great moment of cinematic contempt has Charlotte putting one of the novelty album "laughing records" of the era on the record player so she can cackle at the cuckold by proxy. The growing question is whether her actor is any more suitable—he's a man who only needs a director's command to change his mood.

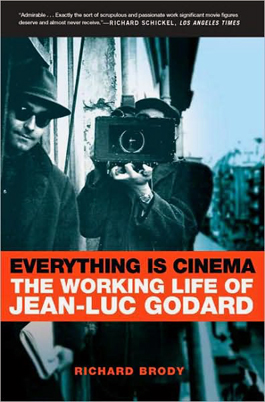

Now in paperback, Richard Brody's Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard (704 pages. $20, Holt) quotes Godard on his three characters: "They are not unhappy, they have nothing but psychological reflexes. ... It's a film in which something is missing." It's a revenge film, too. Godard's muse and lover, Anna Karina, had been unfaithful to him with an actor.

Brody describes Godard's ideas in Une femme mariée as a radical approach to a conservative outlook. Amid the novel, algebraic way of cutting the characters down to size are references to Molière and Racine (the tragedy Berenice read, flatly, in bed, as Charlotte helps the weary Robert learn his lines); the triste Beethoven strings on the soundtrack give context to a drastic stripping down of characters.

Meril plays Charlotte as a chic, decorative object who is good to look at. It's hard to feel for her; she is so caught in the moment and the minutiae of her life that she doesn't know what Auschwitz is. Likely, Charlotte's mix-up of Auschwitz and the thalidomide tragedy is a symbolic gesture, reflecting French historical amnesia. The film was temporarily censored, as Brody records, just as Alain Resnais' Night and Fog was censored. In Resnais' case, the director was required to snip out a visual reference to the French collaboration in the deporting of Jews. Charlotte finally watches the Resnais documentary with Robert at the little cinema theater that used to stand at Orly Airport; only afterward does some kind of conscience awaken in her.

To me the most exciting part of the film is when these flesh-and-blood symbols gave way to actual symbols. First comes a disturbing scene of bathing beauties in printed negative, splashing ink-colored water on one another and grinning with glowing black grins as they are photographed by men with luminous cameras. Soon comes a montage of magazine lingerie ads, if a soft word like lingerie can be used to describe the brutal, almost deforming foundation garments here—the stiff girdles and torpedo bras, amid swirls of advertising copy. Godard cuts to an almost Situationalist cartoon caption. On all sides of Charlotte—swirling around her, in the air around her even—are magazine captions and copywriting: spirals of chatter, the presence of an all-conquering banality.

UNE FEMME MARIÉE; one disc, Koch Lorber; $26.98. EVERYTHING IS CINEMA: THE WORKING LIFE OF JEAN-LUC GODARD by Richard Brody; Holt; 704 pages; $20 paperback

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|