home | metro silicon valley index | features | silicon valley | feature story

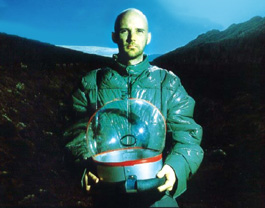

Failure to Launch: Moby is one of the most high-profile advocates of net neutrality. But he and other supporters have been hit with huge setbacks in Congress.

Cyber Crisis

With Congress poised to hand control of the Internet over to large telecom companies, net neutrality is the biggest issue you've never heard of

By Richard Koman

NET neutrality is the hottest issue no one wants to talk about. With ramifications for every single Internet user, anyone who's ever thought about becoming an entrepreneur and policymakers looking at American competitiveness in the coming decades, it's hard to conceive of a more important issue in the technology world.

The question is this: Should the "pipes," the companies that build and control the Internet's infrastructure, be allowed to turn the web into a tiered network, where those who pay more get to deliver their content faster, and everyone else is relegated to the slow lane?

It is a debate that is more critical than ever after last week's defeat of a net neutrality amendment in the Senate. Following a defeat for neutrality in the House, the question of who will control the Internet in the coming years fell into the hands of Senate Republicans: would they allow a net neutrality amendment to a massive telecommunications bill? Last Wednesday, the 22-member Commerce Committee committee rejected the amendment and sent the bill on to the full Senate with only the weakest of protections.

"This vote was a gift to cable and telephone companies, and a slap in the face of every Internet user and consumer," said Sen. John Kerry in a statement. "It will not stand."

But it may stand, unless a parliamentary move by Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) succeeds. Wyden put a "hold" on the bill that may keep it from being voted on until it is amended to include net neutrality provisions.

If last-ditch measures fail, the telecommunications bill that President Bush eventually signs will be one that gives a green light to AT&T, Verizon and Comcast to assert virtually monopolistic control of the net.

It is an issue that has rallied thousands of bloggers and garnered a million signatures on an online petition. Groups as diverse as MoveOn.org and the Christian Coalition have rabid interest. It has launched hordes of lobbyists through the halls of Congress, with the telecom industry spending between $1 million and $5 million a month.

Common Law

A little history: Under longstanding law, telephone companies—and later, cable companies—were defined as "common carriers." With the dawning of the Internet age, that meant that they had to provide access to their networks to competing ISPs, as Internet service providers don't lay copper wire or string coaxial cables; only the telephone companies can do that. In 2002, the FCC reclassified cable Internet as "information services" instead of "telecommunications services," a reclassification that meant that the Comcasts and Cox Cables of the world would not have to allow competitors to use their lines.

In June 2005, in their controversial Brand X Internet Services v. FCC decision, the Supreme Court approved the move. In response, the ACLU railed that "this threatens free speech and privacy. A cable company that has complete control over its customers' access to the Internet could censor their ability to speak, block their access to disfavored information services, monitor their online activity and subtly manipulate the information sources they rely on."

But in August 2005, the FCC showered the same blessings on DSL, the Internet broadband technology offered by the phone companies. Thus freed from common carrier restrictions, the phone companies quickly signaled their intentions.

"The telephone companies and the cable companies have silently stolen the Internet from the consumers," charges Dane Jasper, president and founder of Sonic.net, the North Bay-based independent ISP. "The whole concept of common carriage and access to the last mile—the copper and coaxial cable in the ground, the essential concept that multiple ISPs should be able to deliver service over those facilities—that's been set aside by the Bush administration and the Republican-dominated FCC. The inevitable outcome is monopolization of broadband, and the result is that the cable companies and telephone companies serve more broadband than anybody else by a long, long, long margin."

Free Doom

In an interview with BusinessWeek magazine on Nov. 7, 2005, just nine months after SBC bought AT&T for $16 billion, AT&T chairman Ed Whitaker said about Google and other Internet companies: "How do you think they're going to get to customers? Through a broadband pipe. Cable companies have them. We have them. Now what they would like to do is use my pipes free, but I ain't going to let them do that, because we have spent this capital and we have to have a return on it. ... The Internet can't be free in that sense, because we and the cable companies have made an investment, and for a Google or Yahoo or Vonage or anybody to expect to use these pipes [for] free is nuts!"

Congress is currently rewriting the telecommunications law to allow phone companies to offer high-definition TV services on their networks, among many other changes. As part of those deliberations, Democrats have tried to include language that would preserve net neutrality, but the telecom lobby so far has put the kibosh on such maneuvers.

The arguments against net neutrality are essentially twofold: (1) neutrality constitutes additional regulation, and regulation tends to inhibit growth and innovation; and (2) giving the telephone and cable companies a free hand to invent new revenue models encourages investment in next-generation infrastructure. Of course, there are those like Whitaker who would add a third argument, which states that it's only fair that Google and Amazon and other big users pay their fair share for the new high-speed networks.

Such arguments hold little water with Silicon Valley Rep. Zoe Lofgren. Lofgren has been a leader on this issue since it first appeared. Citing an impending monopoly, she co-sponsored an amendment in the House Judiciary Committee to preserve net neutrality on antitrust grounds. The Republican leadership blocked that amendment, known as the Sensenbrenner-Conyers bill, from coming to a floor vote, instead putting forward an amendment by Rep. Ed Markey (D-Mass.), which went down to defeat along party lines.

"The real issue," explains Lofgren by phone, "is whether the free Internet that we have enjoyed is going to be more like cable television, where the people who control the pipes actually control what you can see, and profit from the content providers paying them to deliver the content. Certainly, people who have content on the net pay now. That's why AT&T and Verizon are making these fabulous profits off of data transmission. But they want more, and in wanting more, they are likely to do terrific damage not only to those of us who use the Internet every single day, but also to innovators."

Does net neutrality really prevent "pipe" owners from charging content owners their fair share? Far from it, according to Paul Misener, Amazon.com's vice president for global public policy, speaking in a debate in Washington in early June. "It's not true that Internet content companies pay for access. We pay handsomely. ... Amazon pays millions of dollars a year to connect to the Internet."

What about regulation? If you accept the notion that the best government is the least government, aren't net neutrality laws a step away from the free marketplace? In an angry statement on the House floor in early June after the Sensenbrenner bill was shut down, Lofgren said, "Antitrust law is not regulation. It's a set of laws that keep monopolies from squeezing the little guys, and that's what's going to happen if we don't get real neutrality."

The issue isn't really about regulating how carriers should behave, says Jasper. "It's that we have just given away the last mile to the monopolists; we've taken the free market away, and now they get to do whatever the heck they want, and suddenly behaviors around neutrality become a potential issue. The inevitable outcome is monopolization of broadband that market pressures cannot correct.

"The path that we're on will mean consumers will not have options. The issue is not legislating neutrality; it's about deregulating access."

Dis-Innovation

What are the likely results of a nonneutral net? Stanford law professor Lawrence Lessig (founder of the copyright alternative system Creative Commons) and Robert McChesney (co-founder of FreePress.net, the media reform organization behind the SavetheInternet.com coalition) laid out the dark vision cogently in a June 8 op-ed for the Washington Post.

"Without net neutrality ... a handful of massive companies would control access and distribution of content, deciding what you get to see and how much it costs. Major industries such as health care, finance, retailing and gambling would face huge tariffs for fast, secure Internet use—all subject to discriminatory and exclusive deal-making with telephone and cable giants. We would lose the opportunity to vastly expand access and distribution of independent news and community information through broadband television. More than 60 percent of web content is created by regular people, not corporations. How will this innovation and production thrive if creators must seek permission from a cartel of network owners?"

Lofgren says it's not just users, but an entire culture of innovation that's at risk. "It's a crucial issue for Internet users, but also looms as a real negative toward nonincumbent innovation. A few short years ago, it was two college kids in a dorm room who had an idea. They could challenge the incumbents, because it was a free and open system. What's going to happen to the next two kids who have a great idea in a dorm room and want to challenge the incumbents? They won't be able to if net neutrality is not preserved. And ultimately that's a disaster for America."

Reach Out and ...

Without some kind of neutrality provisions, critics fear that the pipes will be free to strangle competitors and upstarts. For high-bandwidth applications like video, poor performance equals death. If Google Video suddenly became much faster while YouTube.com continued to suffer the unpredictable state of current Internet delivery, how long would YouTube last?

And what about the broadband telephone system Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP)? The phone companies will obviously run their own VoIP solutions, and it's unlikely that free calling like the peer-to-peer innovation of Skype is in the cards. Says Lofgren, "VoIP is not going to overload the Internet in the way that video files could, but certainly it's a challenge to the incumbent phone companies and one that they could use as power to completely squash the VoIP challengers."

Jasper points out, though, that in today's real world, not all networks are neutral. Peer-to-peer applications like BitTorrent, a popular program for sharing huge music and video files, including pirated movies, "have a huge potential impact on shared networks such as cable and universities," he says. These programs not only allow users to download content from the net but also are set up to upload those files to other users. Thus, a few heavy BitTorrent users can degrade everybody else's performance.

Jasper's concern: Would net neutrality laws prevent network operators from discriminating against applications that degrade performance?

In a word, yes, explains Ben Scott, policy director for FreePress.net. Under the neutrality amendment rejected by the Senate Commerce Committee, network operators "couldn't single out BitTorrent or a particular P2P application; however, they can make bandwidth allocation requirements." In other words, Sonic.net or Sonoma State University could have reduced or cut off service to any users who were using more than their fair share of upstream bandwidth.

"That would provide an adequate level of protection to run a network," says Jasper. "It's always been less than ideal that service providers have impacted whole applications.

"It's worth remembering, says Lofgren, that "the phone companies stifled innovation for a long time until we broke up the monopolies. At one time, you couldn't even buy a phone except from the phone company. It was illegal to hook up an answering machine—that's where they were with innovation. And if we allow them to become that kind of monopoly again, it does not promise a lot of light, innovative approaches to technology."

In his 2001 book The Future of Ideas, Stanford professor Lessig tells the story of Paul Baran, a researcher at the RAND Corporation in the 1960s who was one of the first to envision the network that would become the Internet. Baran attempted to enlist AT&T cooperation to build a network that would be resistant to attack. After a long discussion with Baran, a top AT&T executive exploded. "First, it can't possibly work, and if it did, damned if we are going to allow the creation of a competitor to ourselves."

Ah, writes Lessig, "Here is the essence of the AT&T design, supported by the state-sanctioned monopoly. In 'defending the monopoly,' it reserved to itself the right to decide what telecommunications would be 'allowed.' ... It controlled the wires; nothing but its technology could be attached, and no other system of telecommunications would be permitted. One company, through one research lab, with its vision of how communications should occur, decided."

The modern challenge is not a single-company monopoly, but rather a duopoly or a triopoly as consolidation continues and the walls keep falling between carrier, network, provider, bill collector—and government agent.

Recently, AT&T revealed that it had turned over an undisclosed number of customer records to the National Security Agency as part of the NSA's contested and warrantless claims that a customer's records belong to the company, not the consumer. The Electronic Frontier Foundation has duly brought suit.

Netroots Are Showing?

While little was heard in the mainstream press about the net neutrality issue before the Senate committee vote, over a million people from a broad-based coalition of organizations, businesses and individuals committed to net neutrality have signed an online petition at SavetheInternet.com. Thousands of bloggers have joined the fray, and videos ranging from the professional (Moby) and to the homemade (a female trio called the Broadband, performing "God Save the Internet" ) have popped up on YouTube.com, garnering as many as a quarter-million viewers.

Even such celebrities as Charmed actress Alyssa Milano have become persuasive spokespeople for the cause. On her blog, Milano reasons, "If your Internet provider is Comcast, do you think they will allow quick access to iTunes if they have financial stakes in a different music service?"

Such actions are all part of the netroots movement. The idea is that old-line Democratic grassroots organizing is losing its effectiveness, but that a new online grassroots—a netroots, first manifested in the Howard Dean campaign—is taking hold. Leading liberal blog the Daily Kos, run by Markos Moulitsas Zúniga, recently put on a convention in Las Vegas, the Yearly Kos, where A-list Democrats like Barbara Boxer, Nancy Pelosi and Gen. Wesley Clark paid homage to the rising power of the masses.

Netroots power is real, but it's still a David against the Goliath of entrenched telecom lobbyists, says Craig Aaron, communications director for FreePress.net, the coordinating organization behind SavetheInternet.com. "I don't know of any other issue—previously obscure, highly technical—that has generated this kind of public response in such a short time. The blogs have absolutely gone crazy on this issue. The bloggers deserve a lot of credit for being ahead before the other media started paying attention. About 6,000 different blogs have linked to our webpage. And it's been across the political spectrum."

Although it clearly trends left, the coalition includes such conservative groups as the Christian Coalition and the Gun Owners of America, because concerns certainly don't belong solely to progressives.

The Christian Coalition, for example, worries on its website, "What if a cable company with a pro-choice board of directors decides that it doesn't like a pro-life organization using its high-speed network to encourage pro-life activities? Under the new rules, they could slow down the pro-life website, harming their ability to communicate with other pro-lifers—and it would be legal."

Silent Americans

Online activism is great as far as it goes, but it apparently doesn't go far enough to offset the entrenched relationships, money and lobbying power of the professional and personal relationships in Washington. Rep. Lofgren says that netroots have produced mostly a deafening silence. "During contentious House debate," Lofgren says, "I received maybe 11 emails from net neutrality advocates. eBay sent 6 million emails to their sellers, and I give them credit for doing that, but I haven't received any emails from people identifying themselves as eBay sellers. Nor have I heard any of my colleagues mention it. We're not getting any feedback, we're not hearing from Americans on this subject."

Is there a breakdown between online advocacy and actual communication to Congress?

"It looks like that to me," Lofgren agrees. "The phone companies have taken advantage of the situation. People don't know it's going on, people don't understand what the stakes are, and the net advocates have not been heard from by and large. So [the phone companies] are spending their million-dollars-plus a month on lobbyists, they're doing TV ads, they're doing print ads, they're confusing it. They're saying things that they either know aren't true, or I just can't believe that they're as confused as they seem to be. And so they're winning."

Despite all the traction in the blogosphere, it's hard to break the issue into the real world. Consider the video Moby did on the issue for MoveOn.org. Standing on the Washington Mall, the pop star approaches strangers. The reception is chilly. A female jogger, shakes her head, "No, no, no." An iPod-listening guy says, "Dude! I can't hear you." Moby is disconsolate. "Why won't they listen? Don't people know that their ability to download information from the Internet will be severely compromised if net neutrality is overturned?"

Moby eventually bucks up and, when rebuffed again, won't take no for an answer. He tackles a fellow in dark glasses and forces him to take out his cell phone and call Congress to ask them to save net neutrality.

The tag line? "Don't make Moby tackle you."

Into the Fray

Republican Sen. Ted Stevens of Alaska has been preparing a broad telecom bill, the Communications, Consumer's Choice and Broadband Deployment Act of 2006, that includes only the weakest of net neutrality protections. The net neutrality amendment, called the Internet Freedom Preservation Act, was introduced by Sens. Olympia Snowe (R-Maine) and Byron Dorgan (D-N.D), and closely mirrored the House Judiciary's net neutrality bill, which didn't make it to a vote of the full body, either.

The Internet Freedom Preservation Act would have required broadband providers to offer all content and services on the Internet on a "reasonable and nondiscriminatory" basis, at least equal to the speed and quality offered to the provider's own and affiliated content and services. It banned the imposition of fees based on type of content, and only allowed providers to prioritize content based on the type of content and services. Most importantly, providers were not allowed to charge for prioritizing.

With the failure of the Snowe-Dorgan amendment, things look dire for net neutrality. One alternative, Lofgren suggests, is that the Federal Trade Commission might be willing to engage in a serious turf battle with the FCC over which agency has responsibility here. Commissioner William E. Kovacic told Congress on June 14 that the FCC believes it has jurisdiction over most broadband Internet access services.

And no matter what happens next in the Senate, the battle over net neutrality will continue for some time. Ultimately, the battle lines may shape up differently. As writer Cory Doctorow, a former evangelist with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, wrote recently: "This is the start of the network neutrality fight, not the end of it. Whether you're a geek, an entrepreneur, a wonk or a mere user, there's a place for you in the trenches."

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|