home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | visual arts | review

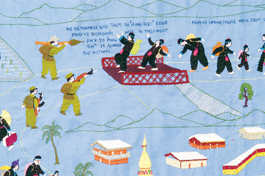

Textile tale of woe: This Hmong story cloth by Pang Xiong Sirirathasuk Sikoun relates incidents from the Vietnam War.

Carpet Bombing

Victims of war from around the world tell their stories in rugs and weavings at the San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles

By Steve Hahn

THE BOMBS hang in midair, as if waiting for a command from above. It is definitely an eerie welcome to visitors walking in the front door of the San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles, surrounding them in an army of pillows that look like they could explode at any second. Deborah Corsini, curator of the museum, hopes this jarring introduction to the new exhibit "Weavings of War" succeeds in penetrating the thick skin of complacency she believes has formed over the American consciousness. "I think we live in a vacuum in this country," Corsini says. "We're very apolitical. Things go on, and we kind of just see it on TV."

Ignoring the harsh realities pf warfare and totalitarian repression abroad is certainly not an option for viewers of the exhibit, which features war-themed textile art from Afghanistan, South Africa, South America, Vietnam and even the United States.

"Unfortunately we had a lot of regions to select from," Corsini says.

There are more reasons than breaking through First World apathy to focus this show, however. Over the last 50 years, guns, tanks, helicopters, land mines, torture and other tools of modern warfare have been making their way into traditional folk art, and collectors have begun to take notice of the dire trend.

In some cases, such as with Afghan rug weaving, the traditional artistic form stays the same, but new militaristic imagery is added into the productions as the everyday experience of the weavers increasingly revolves around warfare and troop mobilization. In other cases, such as the story-cloth productions by the Hmong tribe in Vietnam and the arpilleras created by women in Peru and Chile, new textile traditions have emerged out of the horrors of war and dictatorship.

"It's just evidence that war was prevalent and the weavers were experiencing it," Corsini explains. "This is how they chose to communicate it."

A majority of the rugs in the show come from Afghanistan, and of those, most are drawn from the collection of Patricia Markovich, a Bay Area art collector. Afghan women living at home or involved in commercial rug operations started weaving the tanks and submachine guns they saw the Soviet soldiers carrying in their 1979 march to Kabul.

At first, the images were "hidden" or incredibly subtle, and many buyers would not notice the militaristic imagery. A tank would interrupt a border of flowers, but the tank would resemble the flowers enough to go unnoticed. As the war progressed, the images of weapons became more prominent, eventually overtaking the abstract designs the rugs are famous for. Yet, even with the new subject matter, the old design motifs and patterns manifested themselves.

Traditional techniques, such as borders-within-borders and mirroring images, were maintained in a good number of the rug productions. Some of the rugs broke from tradition and featured maps showing troop movements across the country.

A rug produced at the height of the Soviet-Afghan conflict exemplifies the manner in which new content is poured into the framework of traditional artistic formalities.

The rug features strikingly accurate renditions of Soviet aircraft, armored personnel carriers, helicopters and rocket launchers. The depictions are so accurate, in fact, that the art collector has identified the weaponry down to the model number, even though the weaver of the rug is unknown. The rug is perfectly symmetrical, in keeping with the region's rug weaving tradition, and the bombers, grenades and troop transport vehicles act as a border where abstract designs, plant imagery and prominent buildings would historically be featured.

This rug, and indeed most of the war rugs from Afghanistan, breaks from tradition in one way. Historically, the Koran has been interpreted to forbid the reproduction of "earthly objects" in art. (This is one of the main reasons the Taliban liked to smash TVs so much and why the creations of Islamic artists are usually abstract designs). Yet these rugs depict a variety of objects with stark accuracy, perhaps a testament to the overwhelming visual power of these instruments of war.

The Hmong-produced cloths are distinct in that they tell a specific story with their images. As the war in Vietnam escalated, other countries were dragged into the conflict, including Laos. The CIA was running secret and illegal operations in the country, with the Hmong people as their local collaborators. When the CIA was forced to retreat, they took the Hmong collaborators along with them to prevent Viet Cong retribution.

While some ended up in the United States, many had to stay behind in refugee camps. The squalid conditions in the camps were the birthplace of the Hmong story cloths, as women who would in more peaceful times be stitching abstractly designed embroidery on clothes began coping with their traumatic experiences through storytelling.

Despite the specific origin of the cloths, their storylines often reach back centuries to previous migrations of the Hmong tribe. The cloth featured in the exhibit begins in China circa 1815. As the Chinese began conquering their villages, the Hmong fled to Burma, Thailand, Vietnam and Laos. These routes are depicted on the textile as streams of people departing from a common origin point labeled as China. The "plot" of the story moves along the cloth on a diagonal downward path, showing the Hmong's tragic pattern of peacefully settling down in an area, and then being violently uprooted when caught up in someone else's war. The story ends with the tribe dispersed between refugee camps in Thailand, hideouts in the jungle and evacuations to the United States.

The disturbing imagery is only detectable from a close distance, and the further the viewer steps away from the cloth, the more gorgeous the interplay of color and more striking the level of detail.

Other installations include artistic representations of patriotism, a 9/11-memorial quilt and a quilt about the history of apartheid in South Africa. While the literature accompanying the exhibit is careful not to present the textile art as pro- or antiwar, the overwhelming sense of destitution one gets walking through the peaceful halls of the museum is enough to shake off any trace remnants of privileged aloofness.

"These people have met with the horror of war and what it does," says Corsini passionately. "It's often the women and children who are left behind to tell the stories and who are dealing with the aftermath of war. I think the rug production gives them a voice to [combat] something they were powerless to deal with."

Weavings of War: Fabrics of Memory; Woven Witness: Afghan War Rugs and Afghan Freedom Quilt; and Patriot Art. All end Sept. 23. San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles, 520 S. First St., San Jose. Hours are Tuesday–Sunday, 10am–5pm. Admission is $5–$6.50. (408.971.0323)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|