home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | books | essay

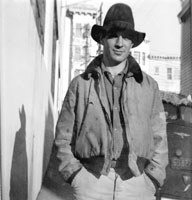

Photograph by Al Hinkle

Beat master: Jack Kerouac in San Francisco early in his traveling years.

Road Warrior

Jack Kerouac's beat classic 'On the Road' keeps rolling on 50 years later

By John Freeman

SIXTY YEARS ago last month, when Jack Kerouac left his mother's house in Ozone Park, Queens, America was a different place. Gas cost 23 cents a gallon. The minimum wage was 40 cents an hour. And simple pleasures came a la mode.

"I've been eating apple pie & ice cream all over Iowa & Nebraska where the food is so good," the aspiring novelist wrote to her on July 24, 1947, halfway into his first cross-country trip. "P.S.," he added. "You ought to see the Cowboys out here."

It took Kerouac another five years to turn what became a series of journeys across the United States into a novel, and by that time his innocence had been scorched away, replaced by a complexly mystical sense of wonder. "Sometimes I go out in the alfalfa field and sleep," he wrote to Neal Cassady, with whom he stayed in Monte Sereno and who would become the inspiration of his future masterpiece, On the Road, from Colorado in 1951. "There are sunflowers and prairie-snowballs and long green fields, and snow mountains: as I said to somebody, 'I am Rubens and this is my Netherlands.'"

Something happened between 1951 and 1957 that made Kerouac a writer and On the Road the book it is today. As the novel's 50th anniversary (on Sept. 5) approaches, some hints about what that might have been are landing in bookstores.

In addition to a collected volume of Kerouac's early novels from the Library of America, Viking has released John Leland's Why Kerouac Matters and a facsimile of the legendary Teletype roll on which Kerouac supposedly banged out a first draft. The publisher has also repackaged Joyce Johnson's Minor Characters: A Beat Memoir.

The scroll is more than a curiosity. It is a pagan artifact of the creative process of which Kerouac—more than any other writer of the postwar years—became an embodiment. Here is the writer writing, says this 120-foot monster of a manuscript. Viking's reissue reprints the text of that beast: all in one long paragraph.

In an enlightening introduction, Howard Cunnell dispels many myths of its creation. It was coffee that fueled Kerouac, not Benzedrine; it wasn't entirely Teletype paper, but "something consciously made by Kerouac. ... He cut the paper into eight pieces of varying lengths and shaped it to fit the typewriter."

Kerouac finished the scroll in April 1951 and immediately began revising. What's shocking is not how much it has changed, but how little. So much of Kerouac's new prose rhythm, his Westward tilt, the music of his sentences is already there.

In fact, a lot of what he had to do to make it a novel involved taking things out—omitting much of the sexual content (including numerous homosexual scenes), changing names of characters (Neal becomes Dean Moriarty, Newark's own Allen Ginsberg is Carlo Marx, etc.), and tightening the structure. He had to make it a novel, not a memoir—and more in tune with its times.

Previous biographies have described this cutting as having occurred against Kerouac's will, but Cunnell argues that's not necessarily the case. Kerouac was apparently desperate to get the book published. It's a piece of the story well underscored by Johnson's beautiful memoir, notable for its feminizing portrait of the time.

She was just 20 years old and working at a literary agency when she met and fell in love with Kerouac on a blind date arranged by Ginsberg. "At 34, Jack's worn down," she writes of her first impression of him, "the energy that had moved him to so many different places gone." This is not the joyous Kerouac we have come so easily to love.

Yet hers is a beautiful, loving portrait that feels at once forgiving and truthful. It acknowledges that a "worm of envy" lived in Kerouac's heart at the success of his friends John Clellon Holmes and Ginsberg. It also hints at the self-destruction to come. "He could see how all the drinking was scaring me," she writes. "He said he felt bad about wearing me out."

It's hard to read this. Long before the booze got him, and the fame turned him into a bloated caricature, Kerouac was a landscape painter with words. His first novel, The Town and the City, was a Bierstadt version of America; for On the Road, he developed more of a pop sensibility. Like Whitman, Kerouac tried to swallow the country whole and sublimate it into an epic form of art. On the Road is his barbaric yawp for America: for its breadth and landscape; for its people and freedoms; for the sheer thrill of traversing it all at great speed.

In language that is lyrical and uncommonly direct, even now, On the Road embodies the great American notion that stretches from Samuel Seabury to Willa Cather: that the country is big enough to house any dream. It is also the book that warns— in its creation, and more aptly, its long aftermath—that achieving that dream could be the worst thing that can happen to you.

On the Road: The Original Scroll, by Jack Kerouac; Viking; 416 pages; $25.95 cloth

On the Road: 50th Anniversary Edition, by Jack Kerouac; Viking; 320 pages; $24.95 cloth

Jack Kerouac: Road Novels 1957–1960, edited by Douglas G. Brinkley; Library of America; $25 cloth

Kerouac: Selected Letters: Volume 1, 1940–1956, edited by Ann Charters; Penguin; 656 pages; $18 paper

Minor Characters: A Beat Memoir, by Joyce Johnson, New York: Penguin; 304 pages; $15 paper

Why Kerouac Matters: The Lessons of On the Road (They're Not What You Think), by John Leland; Viking; 224 pages; $23.95 cloth

John Freeman is president of the National Book Critics Circle.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|