home | metro silicon valley index | features | silicon valley | feature story

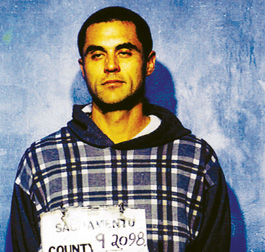

Holding Pattern: The booking photo of Eugene Dey, who's currently doing life at the California Correctional Center for a nonviolent drug conviction under the 'three strikes' law. Dey was first convicted on a meth-related charge in 1988.

My Mistress Meth

The real story of meth in California, from the inside out

By Eugene Alexander Dey

CARVING a crooked path down Highway 80 at 3:30am on Sept. 20, 1998, I was arguing with my girlfriend on the cell phone when a CHP cruiser silently slipped in line behind me. Covered in tattoos and freshly released from prison, my passenger, Raymond Young, manned the stereo like the co-pilot from hell. Neither of us noticed the cops until they flashed their emergency lights.

No longer on parole, I was irritated. Young, a parolee under the influence of a controlled substance, was completely panicked.

Methamphetamine was stashed in my underwear; more was hidden in the engine compartment. As a free man, however, I had complete confidence that the Constitution protected me from unreasonable government intrusions. Under the influence from days of partying, I felt 10 feet tall, bulletproof and on top of my game.

"Hey girl, I'm being pulled over. I'll call you back," I calmly said before clicking off the phone, cutting off my girlfriend's protestations and profanities.

Once pulled over on the side of the freeway by the Antelope exit in Sacramento County, reality slapped me to attention. Always cognizant of how closely peace officers watch a vehicle's occupants, I realized that Young's meth-induced movements—and a few of my own—could escalate our situation. Raymond watched me as I looked into the rearview mirror. I saw two CHP officers clearly ready for a fight. This was not good.

Trying to soothe Young's overstimulated nerves, I composed myself for the ritual of identification and registration. I would utilize my calming gift of gab. "I'll be right back, homeboy. Don't trip," I said with confidence. "I got this covered." I got out of the car.

Walking straight toward cops is a tactic I have always employed to head situations off before they escalate. Besides, since I wasn't a criminal anymore, I felt under no obligation to let others dictate the parameters of my actions.

Within seconds, one of the officers had emptied my pockets and had taken me into custody so fast I could barely say a word. Watching them handcuff Young and force him to the ground helped me to understand that these officers were determined to make an arrest.

When one officer placed a small amount of marijuana on the hood of the cruiser, I tried to downplay the significance. "No big deal," I told myself, "that's just a misdemeanor."

But things steadily grew worse. Hundreds of small baggies that someone had given me weeks prior were placed on the hood. A buck knife that I had long ago thrown in the glove box. Some notes set down in my day planner that were suspected of being pay/owe sheets.

The other officer appeared from under the hood with 20 grams of meth and a digital scale wrapped inside a shirt. In a matter of minutes, two CHP officers simply working the night shift, not narcotic detectives specially trained to locate controlled substances, had amassed quite a cache of evidence. A small marijuana bud tucked into my day planner was found and a stash box I had long ago lost under the car seat was unearthed. Of course, the meth in my underwear was discovered when I was later strip-searched at the Sacramento County Jail.

Since I had similar drug-oriented run-ins with the law in '96 and '97, my attorney, Phil Cozens, guessed I would likely receive a life sentence. He was right. After the judge revoked my bail on Oct. 1, I received the penultimate punishment on May 7, 1999, of 26 years-to-life for possession and transportation of 20 grams of meth—a felony—and about five grams of marijuana, a misdemeanor.

Crankster Gangster

Synonymous in my mind, speed, crystal meth and crank—to name just a few—are all uppers. While stimulants of all varieties have been around forever, speed first experienced widespread usage by soldiers in World War II, and then again by truckers, students, hipsters and bikers in the '50s and '60s. Uppers came in the form of diet pills or street speed manufactured by gangs of outlaw bikers, which could be easily and cheaply purchased.

Then the war on drugs began. When Congress passed the Controlled Substance Act of 1970, elevating methamphetamine to a schedule II drug—one identified as having high potential for abuse—the purchase of widely popular diet pills by prescription became very difficult. By regulating legal speed, the door opened for street speed "cookers" to take a larger role. With little regulation of the chemicals used to cook crank, the purity of meth rose from 30 percent in the early '70s to 60 percent by 1983. Though the chemicals and lab equipment could be purchased without too many obstacles, it took a skilled chemist to pull off the total synthesis of the very dangerous P2P (phenyl-2-propanone) method.

The bike clubs—particularly the Hells Angels, but also other clubs like the Outlaws and Pagans—considered P2P their economic niche. It didn't take the DEA and FBI long to realize that such unregulated chemicals composed the actual lifeblood of the industry. So law enforcement adjusted its strategy and went after the chemicals, the cookers and the bikers all at once.

Back in the day, if someone knew the right people and had the street credibility to be trusted, unlimited amounts of biker speed were available. However, the closer one got to the cooker—the bikers' prized possession—the closer one got to death. These were serious folks, and it took an equally serious to approach those at the upper echelons of the speed gangs.

For this reason, I generally stayed at least one step away from the bikers. Not exactly partial to their form of outlaw militancy, I did my own thing. Nonetheless, I frequently found myself on the brink of madness while under the influence of the P2P meth they manufactured. I had become a full-blown crankster gangster, a spinoff of the bike-club type, but just as independent.

By the late '80s, the main ingredients of speed had literally become impossible to purchase. No matter how much money or how many connections one had, the buying and selling of these chemicals and subsequent manufacturing of the meth became too risky. Innumerable dealers, cookers and members of bike clubs were vigorously prosecuted at the same time. The advocates of the drug war would eventually claim a victory, but it was to be short-lived.

New Chapter

Despite the demise of the bikers' control of the speed trades, meth had already begun to make inroads into the mainstream by the early '90s. Since P2P had become unavailable and most of the old-school cookers were in prison or deep underground, the meth industry simply shifted gears. A simple method allowed for the easy manufacturing of crank, using ephedrine or pseudoephedrine, the main ingredient in cold medication. Now the drug could be manufactured in less than 48 hours, and almost anyone could pull it off.

At the beginning of the war against the bikers, I went to prison in 1988 for my own meth-induced criminality. Young and crazy, I earned my bones—and a 12-year sentence for robbery, burglary, assault, drugs and weapons offenses—during a four-year crime spree. I held my polluted head up high as I entered prison for the first time at the age of 22.

Then reality hit.

Somewhere in my first year of incarceration I decided to grow up. By the time I paroled in 1994, I had three years of college completed, numerous writing credits and an entirely new outlook on life. Through exercise, sobriety and academics, I found sanity. Stubbornly, I considered myself an ex-outlaw rather than a recovering drug addict.

In my new life without speed, I studied sociology at Sacramento State, did activist work for a prisoners' rights organization and started a construction company from scratch. Certain I had found the love of my life, I planned on proposing to my college sweetheart and starting a family.

I closed the chapter of hardcore criminality and opened a new one where I assumed the role of employer, sole proprietor and undergraduate. Leaning toward a graduate education, I had come a long way from the pistol-packing crankster gangster who in 1986 severely wounded a mutual combatant in a street fight that involved a knife, a baseball bat and 200 sutures.

I had left that guy in prison.

Monster Awakens

Having no desire to use meth ever again and having turned it down easily on many occasions, it was my lack of understanding about addiction that led to an eventual relapse in the summer of 1995. Apparently, I had unfinished business with my mistress meth. I ended up snorting a few lines with an old friend, Dennis. One of the few to make it through the meth wars unscathed, Dennis' stories about the craziness I had missed while in prison inadvertently sucked me back into the lifestyle. I had made huge strides, but those couple of lines reawakened an illness that had been dormant for almost eight years.

Though it didn't happen immediately, my increasing involvement in the meth game again affected my better judgment on almost every level. Forgetting how education, not construction, had been my saving grace, I mistakenly concentrated on being a contractor instead of pursuing a graduate degree. Unable to recognize true beauty, I lost interest in my fiancee and pursued a bevy of women of dubious character. Incrementally, I deviated from the solid short-, medium- and long-term game plan I had meticulously developed in prison. I prostituted the integrity of my business by mixing it with pleasure.

Pandora's Box

Though a victory could be claimed in the drug war against the bikers, the Mexican drug cartels immediately filled the cookers' void and put their own signature on the meth business. Flooding the market with cheap speed, they specialized in mass production, superlabs and unlimited Third World workers willing to do the dangerous, dirty work of cooking and distribution. California's Central Valley became the meth capital of the world and is where most of the 6,700 meth labs seized in 2000 were discovered. While the majority are relatively small operations, the cartel's superlabs can produce 10 to 100 pounds in a single "reaction."

Cookers of street speed—those who maintained a death grip on every facet of the business—used to be satanic alchemists who turned dangerous chemicals into huge amounts of cash and power for outlaw bikers and their progeny. Whether the bikers of old were the lesser of the two evils is hard to defend, but the government's actions in regards to meth opened a Pandora's box with the cartels and the microcookers that came into being in the '90s.

With their origins in California, small-time meth operations began popping up all over the country as the relatively simple 48-hour method became a matter of common knowledge in the late '90s. The use and abuse of meth, in addition to the clandestine labs, made inroads into states like Kentucky, South Dakota, Missouri, Tennessee, Indiana, Iowa and Oklahoma. Legislative response grew loud. Suddenly, meth had become an epidemic.

Congressmen John Mica, R-Fla., and Tom Osborne, R-Neb., pushed the Bush administration hard in 2005. Mica stated that the meth epidemic had become "totally out of hand," adding, "This needs to be done on an emergency, expedited basis." Osborne called methamphetamine the "biggest threat to the United States, maybe even including al Qaida."

Rather than concentrate on the difficult-to-corner Mexican-border gangs who produce the bulk of the nation's speed supply, law enforcement focused on the small-time meth makers who rely heavily on the cold tablets. Officers who patrol popular hunting areas provided compelling testimony.

"Before 2000, we'd be hard-pressed to find a meth dump. Now it's not uncommon to find two or three a week," said Patrol Capt. Dennis Whitehead in the April 2006 issue of Outdoor Life. Whitehead works the Daniel Boone National Forest in Kentucky, one of the states hit hardest by the meth labs and the chemical waste they leave behind. Lowell Joslin, chief of law enforcement for the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, added, "It's sad to say, but many of our best hunting and fishing areas are conducive to cooking and dumping meth."

In the 2006 revision of the Patriot Act, new restrictions on the purchase of over-the-counter cold and allergy tablets that contain ephedrine were included in the controversial terrorism legislation. While the Patriot Act has suppressed civil liberties since its inception, the idea of limiting cold tablets like Sudafed came from an Oklahoma law which lead to an 80 percent decrease in meth-lab seizures since it was implemented in April 2004.

Contrary to growing opinion, the average meth addict is by no means a terrorist. In fact, the microcooker is more like a microbrewer who endeavors to expand operations if a market develops. While some are perfectly capable of cooking off larger quantities, the microcooker is rarely able to accumulate the necessary ingredients to do so. They are mostly drug addicts and low-level hustlers; they are by no means cartels. Moreover, cooking meth doesn't produce WMDs, and microcookers have nothing in common with Islamic extremists. Presumably, just like it did in the '80s with P2P, the federal limitations on cold tablets will simply force the meth industry to shift gears yet again.

My Name Is Meth

Buried alive for the last eight years, I am exiled to a California prison for my drug-war transgressions. With an unimaginable 18 years until I'm eligible for parole, I find kinship with toothless, tattooed tough guys from every ethnic and gang affiliation imaginable. Where untreated addiction and chronic hepatitis C are balanced by racism, hatred and violence, I find resolve in the struggle for human rights.

As a 40-year-old nonviolent drug offender serving 26 years-to-life for driving down the road in possession of meth, I am still awaiting the opportunity to earn a release by participating in a treatment program. Instead, addiction is allowed to fester like an open wound. Prisoners spend unholy amounts of time suffering from a myriad of psychological ailments without even being required to identify the root causes behind our deviation from the norm.

Those serving moderate to short stints are simply released back into the world with little hope or chance to succeed. As if by design, California parolees recidivate at the highest rate in the nation.

Since 80 percent of this state's prisoners are estimated to suffer from substance abuse and chemical dependency, prison officials began to implement in-prison treatment programs at the turn of the millennium. Yet only 8,000 beds were established to serve 170,000 inmates, the largest prison population in the country. Since so many drug addicts have co-occurring mental-health and addictive disorders, transforming gulags into therapeutic communities is the perfect transitional criminal justice methodology while solutions to social problems like drug addiction are developed.

Except that this is California, where shoplifters and drug offenders serve life sentences alongside murderers and sexual predators.

I try to transcend the madness through a regimen of exercise, inside activism and literary endeavors. While the vast majority of prisoners exist in an untreated state of active self-destruction, I recently decided to study treatment for the chemically dependent while pursuing an AS in human services. As a would-be paraprofessional in recovery, I study the systems under which we are warehoused.

Up close, I see how untreated addiction works. When meth or heroin enters the institutional black market, I witness firsthand the worst humanity has to offer. The hopelessly addicted will say or do anything to get high—even use a syringe tainted with hepatitis C virus or run up huge debts with no way to pay except through victimization, bloodshed or the betrayal of a fellow inmate.

Like the correctional officers, I simply turn a blind eye.

And with no alternative, my own untreated addiction is exacerbated by imprisonment. I tragically broke my sobriety not long ago. My dreams were skewed, and upon waking, I realized that my affair with Mistress Methamphetamine had resumed. Tormenting me throughout the day as I pay for the rest of eternity, she beckons to me when I am alone at night.

Hell is on earth. I'm in it.

My name is meth and I am not a monster. I am Eugene.

Serving a life sentence for a nonviolent drug conviction under the 'three strikes' law, writer Eugene Dey is an inmate at the California Correctional Center in Susanville. His memoir, 'A Three-Strikes Sojourn,' received a 2006 honorable mention from the PEN American Center.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|