home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | books | review

Into the Gap

Two new books explore the painful divide between the rich and the rest of us.

By Michael S. Gant

A RECENT STORY from London tells of a hedge-fund manager who didn't have the time to claim his $160,000 Maserati after it was towed for unpaid parking tickets. Hedge-fund managers are the new poster spoiled-children for income inequality. A study by United for a Fair Economy and the Institute for Policy Studies calculated that the top hedgers received 22,255 times the typical yearly pay of an American worker. That makes the average CEO look like a piker—he earned only 364 times what a working stiff gets in a year.

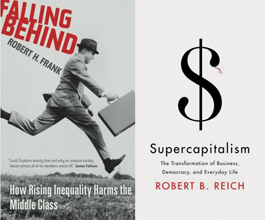

Inequality and the damage it is doing to our economy and our psyches is the subject of two important new books: former Clinton Secretary of Labor Robert Reich's Supercapitalism: The Transformation of Business, Democracy, and Everyday Life (Knopf; 272 pages; $25 cloth) and economist Robert H. Frank's Falling Behind: How Rising Inequality Harms the Middle Class (UC Press; 148 pages; $19.95 paper). Both analyze how we got to this parlous state, but neither can provide more than some vague hope for the future. More than once Frank figuratively throws his hands in the air in despair: "How, historians will ask, did people who denied the existence of tragedies of the commons ever get anyone to take them seriously? I don't have a good answer to that."

Reich looks back with nostalgia on a postwar era in which all families enjoyed real income growth, and corporations and labor agreed on regulations and self-controls that benefited almost everyone—"steady jobs at good wages within a system that broadly shared the fruits of prosperity." But advances in technology led to economies of scale and improvements in distribution that created better deals for consumers (iPods! Wal-Mart!) and investors at the expense of democratic and social values. As a result, by 2004, the 1 percent at the top of the food chain sucked up 16 percent of total income, twice what they got in 1980.

The result, Reich writes, is that "markets have become hugely efficient at responding to individual desires for better deals but are quite bad at responding to goals we would like to achieve together." It's a good news/bad news setup: we can buy cheaper and cheaper new stuff at Wal-Mart, but we have less and less to spend thanks to depressed wages at Wal-Mart (the recent bump up in the minimum wage still leaves it, adjusted for inflation, 7 percent below what it was a decade ago). Reich argues that it is a mistake to attack corporations like Wal-Mart for their social failures. Wal-Mart, like all corporations, is simply an engine designed to produce value for stockholders. The only way in Reich's scheme to achieve change is to do so at the macro level, by passing laws and regulations defining and enforcing responsible behavior. The baleful influence of corporate lobbyists, however, has drowned out the voices of reform.

Reich's answers sound a little thin. Maybe, just maybe, corporations would agree to a cease-fire in lobbying escalation, but as Reich admits, no serious legislation will come from politicians beholden to corporate money—"The system cannot reform itself from inside." Reich also suggests some weak-tea solutions: more unemployment insurance, job training for the laid-off, an opt-out clause for shareholders who disagree with a corporation's politicking. His best thought is more conceptual. He wants to stop the legal fiction of treating corporations as "individuals" with the rights of real people. This might help curb the absurd argument that corporations have free-speech rights. In the meantime, despite Reich's misgivings, activists might still gain some traction by pressuring large corporations to at least pretend to do the right thing. It sure beats waiting around for the courts and Congress to tackle the larger systemic fractures in our economy.

Frank makes many of the same points as Reich, noting the main inequality problem: "The bottom 40 percent of households actually experienced a significant decline in net worth between 1983 and 1998." The real strain, Frank writes, comes because "people care about relative consumption" in some significant areas. That means, for example, that as the rich spend more and more on housing, the middle class will be forced to keep up in relative terms, even if it means saving less and assuming more debt.

Falling Behind points out that inequality is literally killing us, because "greater inequality is associated with a variety of adverse health outcomes." Again, his solutions are tepid. It might make sense for the ultrarich to cool it, because what is "smart for one is dumb for all," but who's going to go first: Bill Gates or Donald Trump? Frank also proposes some legislation for enforcing savings through a progressive consumption tax, an idea whose details can be easily demonized by the Republicans who brought us the disastrous Bush tax cuts. Even so, the effort is worth it, because as Frank demonstrates, high inequality is actually counterproductive, because it slows the overall growth of the economy.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|