home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | books | review

Kern County Museum

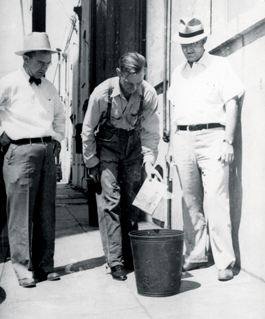

THE FIRE LAST TIME:A farmworker named Clell Pruett consigns 'The Grapes of Warth' to the fire as his boss, Bill Camp, and L.E. Plymale watch.

Trampling 'Grapes'

'Obscene in the Extreme' recalls the fight to ban John Steinbeck's great novel

Reviewed by Geoffrey Dunn

JOHN STEINBECK'S Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, The Grapes of Wrath, jumped onto the bestseller list in the spring of 1939 and forced the plight of Dust Bowl immigrants working in the fields and fruit orchards of California into the American consciousness. As Rick Wartzman points out in his important and illuminating new book, Obscene in the Extreme, Steinbeck's novel "seared into the public's imagination forever." Made into a superb film by John Ford and starring Henry Fonda as the beleaguered "Okie" Tom Joad, The Grapes of Wrath, as both novel and film, has come to define the oppressive nature of farm labor in California for nearly three-quarters of a century.

Make no mistake about it: Steinbeck's novel (written at his home in Los Gatos, by the way) was a radical piece of literature. Most people have forgotten its literary prequel, In Dubious Battle (1936), in which Steinbeck depicted the agricultural proletariat as caught between two evils: corporate agriculture and leftist (often Communist) union organizers. The Grapes of Wrath made no such equivocation; Steinbeck was clearly coming down firmly on the side of unions and against the growers and big land owners. "This is a rough book," Steinbeck declared, "because a revolution is going on."

Seventy years later, with The Grapes of Wrath canonized in American literature and still a must-read for students across the country, it is almost forgotten how strongly—and even violently—publication of Steinbeck's novel was opposed in the heartland of California. Obscene in the Extreme dutifully chronicles this forgotten history. For many Dust Bowl migrants, their first stop in California along Route 66 was Bakersfield, in Kern County, at the southern rim of the fertile San Joaquin Valley. Their arrival was often met with ostracism and disdain. There were signs on restaurants and gas stations that read: "No Niggers and Okies Allowed." The overwhelming success of the novel and the prospects of an oncoming film infuriated the powers-that-be in Bakersfield. On Aug. 21, 1939, at the behest of the Associated Farmers of California, a fervently anti-union organization, the Kern County Board of Supervisors in Bakersfield passed a resolution declaring that the novel had presented "our public officials, law enforcement officers and civil administrators, businessmen, farmers and ordinary citizens as inhumane vigilantes," and that it was filled with profanity, lewd, foul and obscene language unfit for use in American homes." Not only did the resolution ban the book from appearing in Kern County libraries and schools, it also called for 20th Century-Fox to cease production of the film. Three days later, the book was burned with the support of Associated Farmers state treasurer Bill Camp. Similar burnings took place around the state—and the country. "We are angry not because we were attacked, but because we were attacked by a book obscene in the extreme sense of the word," Camp declared. Enter Kern County librarian Gretchen Knief, who stood up on the side of the First Amendment against the powers that be. Knief, 37 at the time of the censorship, compared the burning to similar acts of repression by the Nazis in Europe and asserted that "banning books is so utterly hopeless and futile. Ideas don't die because a book is forbidden reading."

Wartzman chronicles the ensuing two-year battle, in which the David-like Knief prevailed over the Goliath of agribusiness, with balance and detail, though his sympathies clearly reside with Steinbeck and Knief. In 1941, with a new Board of Supervisors in power, the ban was eventually revoked. Such book burnings might seem like distant rumblings, but in light of revelations coming out of Wasilla, Alaska, this past month, the dynamics of this iconic battle over censorship remain all the more relevant. "A book is somehow sacred," Steinbeck himself declared. "A dictator can kill and maim people, can sink to any kind of tyranny and only be hated, but when books are burned, the ultimate in tyranny has happened. This we cannot forgive."

OBSCENE IN THE EXTREME: THE BURNING AND BANNING OF JOHN STEINBECK'S 'THE GRAPES OF WRATH' by Rick Wartzman; Public Affairs; 308 pages; $26.95 hardback. Wartzman appears Wednesday (Sept. 24) at 7:30pm at Kepler's in Menlo Park, and Thursday at 7:30pm in Room 550 at the King Library in San Jose.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|