home | metro silicon valley index | music & nightlife | band review

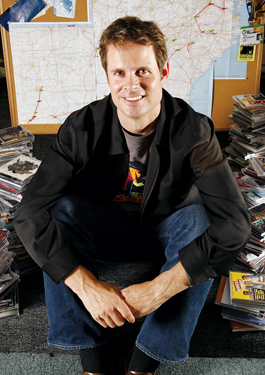

ERA ERA: Pandora's Tim Westergren programs for individual listeners—on a mass scale.

Radio Your Way

Internet powerhouse Pandora may just save the music industry

By David Sason

LAST THURSDAY, Dominican University of California in San Rafael hosted a very different kind of town hall meeting. While no fundamentalists were apparent, a near-religious fervor pervaded the lecture hall for the latest Pandora "Get-Together," hosted by the popular Internet radio and music-discovery service.

"I'm the chief evangelist," founder Tim Westergren told the classroom with a laugh. No wonder, since Oakland-based Pandora is today's premier online radio service, boasting 35 million listeners across the United States, with 65,000 new registered listeners a day.

It's readily obvious by talking with the young-looking 43-year-old that he enjoys his job. Back in 2000, along with Will Glaser and Jon Kraft, the Stanford graduate began the ambitious Music Genome Project, a scientific examination of songs using vectors and algorithms that eventually led to the creation of Pandora, a music aggregate that dispenses songs in the form of "stations" that are completely unique for each listener.

First, a listener picks an artist or genre to create a "station." The user's tastes are determined each time he or she clicks "thumbs-up" or "thumbs-down" buttons indicating preference; the "skip" button is neutral. To ensure exposure to new music, no more than four songs from the same artist are played in a three-hour period on any given user's station.

"Every submission gets a listen," Westergren says of the 12,000 new songs that come in per month, "but it has to be good." To increase critical consistency, each of Pandora's 50 music analysts typically holds a four-year degree in music theory and undergoes a rigorous 100-hour training regimen.

Such an innovative approach to radio engenders interesting challenges, as with eclectic artists. "A station based on Frank Zappa doesn't work very well," Westergren says, "and Beck is a pain in the ass, musicologically speaking." The technology can sometimes be jarring, as in the case of a young man who was irate that a Celine Dion song played on his Sarah McLachlan station.

After Westergren verified that all the variables worked, nothing was left but the ugly truth. "His last email said, 'Oh my God, I like Celine Dion!'" Westergren laughs. "We don't put much stock in cultural prejudices."

Just as admirable is Pandora's bucking of major record labels. Westergren says that "77 percent of our artists are independent." As a touring musician himself for years—he played in a band called Yellowwood Junction—Westergren hasn't forgotten the musician's struggle to make a living. Through Pandora, he says, he can offer a new revenue stream for artists.

While Pandora makes money from ads on its site and commission from music sales through iTunes and Amazon, the company has never advertised, relying purely on word of mouth. When the Copyright Royalty Board ruling tripled its required royalty payments in 2007, Pandora was saved by its supporters, with 400,000 letters and faxes reaching Capitol Hill in three days—more than those protesting the Iraq war.

"This is definitely disturbing, but it's fine for us," he says, and resulting negotiations enabled Pandora to stay afloat.

This devotion was fully visible at Dominican, with people of all ages thanking Westergren. "You nailed it," a middle-aged lady gushed. "I've had really strange taste my entire life, and now I've gotten into so much new music!" While one older gentleman found Pandora's classical offerings too limited, most were elated with the service.

According to Westergren, Pandora's biggest competitor is traditional radio. "Those are the listeners we want," he says. "Most of our listeners are in their 20s and 30s, but our fastest growth [is with listeners who are] far older. And they're no longer being served by the broadcast industry."

Pandora supports the controversial Performance Rights Act, which would require radio stations to pay royalties to musicians. Pandora already does this. "We think the performer should be paid for radio play," Westergren says simply.

While Pandora isn't profitable yet—Westergren hopes to be by year's end—its achievement remains a scintillating reminder of why music fans should run the music business. "You will never hear a song on Pandora because a record label told us to," Westergren told the group to rapturous applause.

That's an algorithm that deserves a huge thumbs-up.

Pandora can be found at www.pandora.com.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|