home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | books | author profile

Photograph by Felipe Buitrago

Romancing the stone: The Rosicrucian Museum is one of the central landmarks on Erik Davis' unorthodox California map.

Urban Legends

Erik Davis' new book 'The Visionary State' is a mystic trip through the landscape of California, with plenty of stop-offs right here in Silicon Valley

By Gary Singh

ERIK DAVIS claims that he was born and raised a California heathen, in the sense that he was never baptized and instead found himself tripping around with yogis, monks and even born-again surfers. He has ridden the wave of every bizarre spiritual skein making up this land we call California, and he has written on everything from virtual-reality shamans to Extropian transcendentalists to ravers and technopagans. He even employed rock journalism as alchemy to analyze Led Zeppelin's fourth album.

So it only makes sense that his latest venture is a mammoth tag-team effort with photographer Michael Rauner, a glossy elephantine photo/text exploration through all of this state's bizarre spiritual trajectories. In The Visionary State, a Journey Through California's Spiritual Landscape, Davis and Rauner uncover a landscape that is uniquely Californian in scope. You can't grow up in North Dakota and get exposed to druid libraries, high-tech pop occulture, teen Wiccans, EST seminars, a satanist with a roomful of mannequins in his basement, Deadheads, tantric yogis, LSD mystics and Hare Krishnas all as part of the same topography. Consider the book a Bay Area Backroads episode, but instead of the Winchester Mystery House, you've got an elaboration on the spiritual aspects of research at SRI International in Menlo Park or the struggles of the Sikh temple in San Jose's Evergreen neighborhood.

"It was both out of intellectual interest in the history of alternative spirituality, which is an abiding interest of mine, but it was also a personal quest," Davis explained. "I wanted to know about the forces that shape me, and so much of what I still do."

San Jose pops up in another chapter, with Davis placing Lick Observatory in a visionary context: "The most visionary of the sciences—in the spiritual as well as the literal sense of the term—remains the least practical: astronomy. Here, too, California has sometimes led the way, reshaping and unsettling our place in the universe with cosmic insights that depend on marvelous machines."

Rauner's photographs and Davis' texts play off each other, and although Davis had most of the research done by the time Rauner came on board, this project would not have worked without the photographs. As soon as you open the book, the first photo shows a shot of the Self-Realization temple on a beachfront cliff near Encinitas with a "surfer crossing" sign in the foreground. The juxtaposition makes one immediately think, "Only in California." The photo rightfully sums up the entire book, providing the reader with a perfect breakdown of what's to come.

"As soon as I saw that conjunction, I was like, 'Oh, my God, this has to be the photograph, this has to be the icon of the beginning of the book,'" said Davis. "Because it totally expresses the conjunction of popular culture, of outdoor hedonism and this kind of exotic theme park quality of so much of this alternative religious strain in California. So I was very insistent that Michael get a good photograph of that place."

So Davis journeyed in, around and between all these different spots and stories, his exploration taking the form of psychogeography, a subconscious drift through places with no intended final destination. Taken from the Situationist International, a radical French art and political movement in the '50s, psychogeography is related to the concept of dérive, which translates as "drifting," and in Situationist parlance refers to locomotion without a goal or to a mode of experimental behavior having to do with a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences.

Photograph by Michael Rauner

Other local stops: 'The Visionary State' also looks at San Jose's Sikh Gurdwara.

"When I first realized that I wanted to tell the story in terms of visiting these places—obviously that implies a kind of geographical way of organizing it—but I didn't really discover that deeper element until I was actually on the journey," Davis explained. "I think one of the attractions of psychogeography is that it reinvests a sense of place that many of us don't have, probably because the world we live in is increasingly placeless, increasingly incorporeal—we spend more time in front of screens or on phones. Also, every place is beginning to resemble every other place, especially in California, with strips malls and housing developments, yadda, yadda, yadda. It really erodes our sense of place. And doing the kinds of journeys that I have been—seeking out these traces of these older stories, it really transforms my relationship to place. So for me, psychogeography is not just about telling stories that are hidden in the land, but a kind of re-enchantment of the landscape. ... It's like an invocation of ghosts. ... It's not just like empty history in a history book, it's about different layers and strata of the cultural geography. In order to combat the existential emptiness of the endless strip mall experience and this kind of desert of crap, it becomes a way of [seeing] local history as a survival mechanism, as a way of reimagining, not just as a way of passing the time."

Situationist Guy Debord explained psychogeography this way: "The sudden change of ambiance in a place within the space of a few meters; the evident division of California into zones of distinct psychic atmospheres; the path of least resistance which is automatically followed in aimless strolls (and which has no relation to the physical contour of the ground); the appealing or repelling character of certain places—all this seems to be neglected."

Which is precisely why this book needed to happen. You just want to aimlessly explore these interstitial places and get the stories yourself. Why go to the San Diego Zoo when you can skip up the highway and visit sporting goods king Albert Spalding's old residence, one of the few structures remaining from Lomaland, a turn-of-the century occult community devoted to reviving the lost mysteries of antiquity? If you're in Culver City, who cares about Sony Picture Studios when you can go check out the King Fahd Mosque? And how can you possibly visit Marin County without trying to locate Druid Heights, a legendary beatnik enclave where everyone from Alan Watts to Neil Young showed up? Well, Davis did all that.

"I did it mostly just as an excuse to get out—to go visit different parts of the state that I hadn't been to," Davis said. "And also to make it more of a personal pilgrimage. By going to these places, I felt like I was picking up something, some energy, some atmosphere, some quality of place. It was communicating something that I wasn't getting just by doing the research or interviewing people."

In the following excerpt, Davis vamps on San Jose's Rosicrucian Museum, a place that everyone in San Jose knows about but doesn't know about. Judge for yourself.

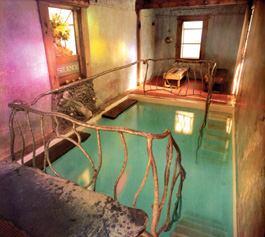

Photograph by Michael Rauner

Reflecting pool: Harbin Hot Springs in Lake County, another 'Visionary State' destination.

The Rosy Cross Parade

IN the early seventeenth century, so the story goes, two European explorers sailing off the coast of Carmel came ashore with a stash of esoteric documents, which they buried with an eye toward future generations of California mystics. According to the West Coast occultist who claimed to have discovered these texts, the two men were Rosicrucians, initiates in a mystery tradition that some trace back to the wisdom schools of ancient Egypt but that conventional historians date to a series of popular pamphlets that appeared in Europe in the early 1600s. These manifestoes proclaimed the existence of a secret order of Christian alchemists working for the enlightenment of the world. The chapbooks were most likely esoteric fictions, the Carlos Castañeda books of their day. But so many men wanted to join up that actual fraternal orders emerged, each taking as its central icon the rose blooming at the heart of the cross—a symbol of, among other things, the spiritual life blossoming forth from the material body.

The man who claimed to have disinterred Rosicrucian documents from California's soil was H. Spencer Lewis, an energetic Egyptophile and adman who founded the Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis in New York in 1915. Lewis was initiated by a Rosicrucian master in Toulouse and spent time as well in the Ordo Templi Orientis, an occult order led by the notorious Aleister Crowley; Spence took AMORC's Rosicrucian emblem from the pages of Crowley's journal, The Equinox. In 1927, Lewis purchased a modest plot of land amid the luscious apricot and peach orchards that once thronged San Jose. The Grand Imperator dubbed the property Rosicrucian Park, which would become home base for the largest and most famous Rosicrucian group in America.

Today Rosicrucian Park is one of the crown jewels of California's visionary landscape. An inviting maze of temples, fountains, statues, plants, and bas-relief gods, the site is part Egyptian Revival, part Deco, and part Disney. (Walt Disney, it should be mentioned, was once a member of AMORC, as was Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry.) Though Lewis saved his heaviest sacred designs for the interior of the windowless main temple, the park's grounds and exteriors stand as a public monument to the esoteric imagination. Rosicrucian Park also includes the largest Egyptian museum in the western United States, a collection of coffins, mummified baboons, and stelae—as well as a few items of dodgy provenance—housed inside a massive mock-up of the Temple of Amon at Karnak. A goofy statue of a pregnant hippopotamus goddess greets visitors, who pass through a dramatic peristyle and huge bronze doors before entering the museum. The theatrical deployment of sacred space carries on inside the building, where hordes of schoolchildren are regularly hustled through a full-scale reproduction of a Middle Kingdom tomb.

Outside the museum, Rosicrucian Park continues to work its magic through exotic stage sets and symbolically coded environments—a kind of mythic theming that extends even to the flora, which includes papyrus, lilies-of-the-Nile, and scores of roses. Entering the park from the northwest corner, one passes through a small pylon gate with a painted relief of a scene from the Egyptian afterlife: the baboon of Thoth preparing to weigh the hearts of the dead against the feather of Ma'at. Passing through this threshold of judgment, one enters a landscape that lies, in a sense, between the worlds. The diminutive scale of the gateway and the rosy obelisk that stands nearby—the first in America—recalls the toylike dimension of the eclectic period villages at Disneyland or Epcot Center. One is therefore hardly surprised to see a Moorish building break up the Egyptian theme. Designed and somehow built during the Depression, this recently restored planetarium—a green dome with an octagonal base, tri-lobed archways, and a zigzag facade flanked by narrow corner towers—honors the Islamic scholars who kept ancient Greek science alive. Near this temple to the stars stands a bronze replica of a famous Roman statue of Augustus Caesar. Behind this cheerily incongruous mixture of times and places lies a deeper claim—that an unbroken stream of wisdom has passed through the ages, from Egypt's Middle Kingdom through Greco-Roman civilization and medieval Islam all the way to contemporary San Jose.

In the sunken patio at the heart of the park stands the Fountain of the Living Waters, an energetic focal point whose colored mosaic tiles and lion's-head reliefs encode alchemical secrets. Two stone sphinxes nearby guard the entrance to the Rose-Croix University International, whose classical Egyptian facade includes columns that resemble bundles of papyrus. The university, which is now closed, once contained chemistry labs, darkrooms, and classrooms, and reflected the modern mystic dream of embedding science in the cosmic context of ancient harmonies. Lewis was himself an inventor and engineer. In addition to building the projector for the planetarium—the first such device made by an American—the Imperator also constructed a color organ, which represented the frequencies of different musical tones as colored lights that danced across the sort of triangular screen you might expect to see in a 1950s flying saucer movie.

Across the patio from the university stands one of the park's earliest and most lovely spots, a small shrine to Pharaoh Akhnaton that is reserved for those who pony up $215 a year for an AMORC membership. Built in honor of initiations that Lewis conducted in Luxor, Egypt, in 1929, this simple colonnade, fringed with papyrus plants and dark green elephant ears, now houses the Imperator's ashes, stored beneath a small pyramid inscribed with the single word Lux; a nearby ankh reflects the hope for immortality that ties together ancient kings and modern mystagogues. It is a sign of AMORC's health that, unlike so many esoteric orders of the early twentieth century, it has survived the death of its charismatic founder. Long after the passing of Lewis and his son Ralph, who served as Grand Imperator until 1987, AMORC's incarnation of the Rosicrucian dream shuffles along. And much of the reason lies with the park itself, an open secret that satisfies needs as civic as they are mystic.

Photograph by Michael Rauner

Close encounter: The Vallejo in Sausalito.

One sacred stream that runs thin at the AMORC headquarters is the Christian revelation, a somewhat odd scenario given the allegorical connotations of the rose and cross. Other modern Rosicrucian groups pay far more attention to Jesus than to Akhnaton, and one of these orders also built a large and intriguing compound in California. Like Lewis, Max Heindel met a mysterious Rosicrucian master while visiting Europe; afterward, he returned to the United States to found his own order in Seattle in 1909. Heindel soon moved his Rosicrucian Fellowship to Southern California, where, the Elder Brothers informed him, the electrical currents were best attuned to the approaching Aquarian age. Heindel settled in Oceanside, on a high southern overlook of the broad San Luis Rey Valley, close to what is now the boundary of the U.S. Marine Corps base Camp Pendleton. Here on Mount Ecclesia, Heindel built a small mission-style chapel to hold healing services based on his Aquarian blend of astrology and Christian mysticism.

The community grew, and Mount Ecclesia today includes a cafeteria, a print shop, small homes, and a large guesthouse that services Rosicrucians who trickle in from South America, Africa, and Europe. At the center of the property lies a voluptuous rose garden and a fanciful lotus pond surrounded by calla lilies, lavender, papyrus, and datura. The Healing Department takes up a small cruciform bungalow nearby; here secretaries handle the correspondence of fellowship members seeking the healing balm of the Invisible Helpers.

A hushed if somewhat claustrophobic twelve-sided chapel nestles in the crux of the building, its placement corresponding to the location of the rose in the Rosicrucian emblem. Diffuse light filters into the chapel through a small art-glass dome on the ceiling, while the room's pastel colors seem to dissolve the solid walls into the diaphanous vibrations of the higher planes. Besides a rosy cross, the main icons in the chapel are zodiac symbols and a great big Bible—a fitting juxtaposition for folks who hold that the Son of God corresponds more or less directly with the sun in the heavens.

The finest building in the compound is the Healing Temple, which tops Mount Ecclesia. A large white concrete rotunda, the temple was Heindel's last major project on the property before he died in 1920. The twelve sides of the building correspond to the twelve signs of the zodiac; this division is carried on inside, where students sit in sections according to their natal sun signs. The building has an air of secret rites; students must study as probationers for a few years before gaining access to the round hall, hidden from outside eyes by marblesque windowpanes in opalescent green and blue. Two squat palm trees echo the two pillars that frame the entrance to the building, whose hardwood doors are carved with Art Nouveau images of Leo and Aquarius. The most curious element of the building is the nine-pointed star-shaped doohicky that tops the rotunda; it looks like the model of an atom from a 1960s filmstrip. Even in its somewhat dilapidated state, Mount Ecclesia still traces the lineaments of the visionary. According to one resident, "Some probationers in Africa think the Elder Brothers actually live here."

The Visionary State: A Journey Through California's Spiritual Landscape; Chronicle; 272 pages; $40 cloth. Erik Davis will be reading in Santa Cruz on Thursday, Oct. 5, at 7pm at Gateways, 1126 Soquel Ave., Santa Cruz; 831.429.9600.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|