home | metro silicon valley index | music & nightlife | band review

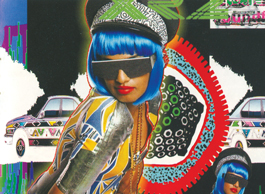

BIG TIMER: M.I.A. represents the world town on 'Kala.'

Radio On

With her new album 'Kala,' M.I.A. blows up musical history to make way for its future

By Steve Palopoli

ON what is supposedly the Sex Pistols' first-ever studio recording, a voice from the control room can be heard springing it on lead singer Johnny Rotten that he is expected to sing Chuck Berry's "Johnny B. Goode." The band rips into it, but the once and future John Lydon quickly gets bored, giving up his halfhearted vocals to suddenly yell at guitarist Steve Jones: "I know! Hey Steve, 'Roadrunner'! 'Roadrunner'! Should we do 'Roadrunner'?"

Without missing a beat, the other Pistols swing into the song that Jonathan Richman had released with the Modern Lovers a year earlier. But Rotten just laughs. "I don't know the words," he admits. "I don't know how it starts. I've forgotten it."

It's not a cover, it's a massacre. By the time Rotten gets to the part he really knows—"With the radio on!"—rock & roll is changed, or at least shaken up. The Sex Pistols are playing something incredible, but it isn't "Roadrunner." Rotten is spewing a flood of free-associative words that barely match the real lyrics, and the guitar, bass and drums swirl into a roar that rolls to the edge of a sonic cliff and then drops off it. Having turned two rock classics inside out in the space of five minutes, Rotten sighs "Do we know any other fucking songs that we could do?"

The Pistols would move from deconstructing "Roadrunner" to being considered the most dangerous band in the world, then claiming they did it all for the money, then imploding.

M.IA. Coming Back With Power, Power

Exactly 30 years later, Maya Arulpragasam, also known as M.I.A., follows in Johnny Rotten's footsteps by opening her second album, Kala, with a misquoting of the same Modern Lovers anthem: "Roadrunner, roadrunner, going hundred mile per hour, with your radio on," she sings at the beginning of "Bamboo Banga."

This time, though, it's obviously not that she doesn't know the words, it's just that she doesn't care. Like the Sex Pistols, she launches off of Richman's riff to create something entirely different. "Bamboo Banga" is her own manifesto, in which she more or less dares the listener to think that her first, overhyped single, 2004's "Galang," and her controversial debut record, 2005's Arular, were a flash in the pan. She knows the whole world is thinking sophomore slump. And she knows they're not going to believe what they hear in the next 47 minutes and 34 seconds: "Now I'm sittin' down chillin' on some gun powder/ Strike match light fire/ Who's that girl called Maya?/ M.I.A. comin' back with power, power."

Much has been written already about the staggering patchwork of global sound on Kala, and rightfully so. Not since the heyday of Afropop king Fela Kuti—1977's Zombie, maybe—has a record sounded so goddamn international. Arulpragasam was born in London, was in and out of her parents' homeland Sri Lanka and lived in India, as well. None of that was all that obvious musically on her post-electroclash first album, but Kala is literally all over the map. Kuti himself would be impressed by her fusing of pan-African influences with the current British rapgirl zeitgeist; she also samples Sri Lankan films, and even includes her own version of an '80s Bollywood tune, "Jimmy."

But there's something else going on here, too—Kala practically charts a history of alternative rock. Arulpragasam has ripped her pages straight from the Sex Pistols playbook: she doesn't cover the songs of her heroes on this album so much as rip them to shreds and rebuild them into new classics that are unmistakably and completely hers.

In this regard, she's taken a giant leap forward from Arular—on that record, she name-dropped rock and hip-hop icons, on this record she has her way with them. It might have been enough two years ago to rap about "laying low and jacking up to Lou Reed," but with her "Roadrunner" remodel she blows up the defining classic of Reed's number one disciple Richman. And where she previously mentioned "chasin' out to Pixies" in passing, on Kala she morphs "20 Dollar" into an almost-cover of "Where Is My Mind?"—one that's grafted onto the riff from New Order's "Blue Monday."

M.I.A. the rock-giant killer doesn't stop there. On "Galang," she referenced the Clash, but three years later she's put the new album's best song, "Paper Planes," to the backing track of the Clash's "Straight to Hell." "Sampling" does not describe this audacious lifting of the song—it's more like she's put her new words over their old song, with a few added beats and sound effects.

As a true measure of her power, power, however, none of these compare to the woman who once wrote about "Freakin' out to Missy on a Timbaland" actually landing Timbaland as Kala's co-producer. Certainly he seizes the opportunity to take his own work to another level, as well—"Oops (Oh My)" this is not.

I'm Knocking on The Doors of Your Hummer, Hummer

M.I.A. is capable of changing how we think about the past and future of music, but what remains to be seen is if she'll be considered as dangerous as the Sex Pistols were in their post-"Roadrunner" run. From the best available evidence, she's far more so. And if there's anything both hip-hop and rock need right now, it's a little danger.

The Pistols may have sang about being Antichrists and anarchists, they may have implored the world's youth to "get pissed—destroy." But Arulpragasam dares to sing about bombs and insurrection. Not necessarily what might be considered the best career move when your father is famously a separatist with the Tamil Tigers, a group perhaps best known for carrying out suicide bombings, even against civilians, in their ongoing battle for a separate Tamil state in Sri Lanka. Whether you consider them freedom fighters or terrorists, the history of the organization is a bloody and violent one. Arulpragasam named her first album after her father; this one is named after her mother, who she clearly considers just as much of a revolutionary. It's one thing for her to sing "Pull up the people/ Pull up the poor" on Arular, but considering her family history it's a shock to hear her rap "I've got the bombs to make you blow" in the same song. Similarly, considering that the Tamil Tigers have been accused of using children as soldiers, it is almost unbelievable to see the video for the upbeat "Boyz," the first single from Kala, in which Arulpragasam dances with young black men while singing "How many no money boys are crazy/ How many boys are raw?/ How many no money boys are rowdy?/ How many start a war?" Is she saying they should start a war? Mocking those that do? The lyrics are so (purposefully?) ambiguous it's hard to tell. Every song on the new album has some connection to the theme of revolution, as it bounces disorientingly between militarism and humanism.

In respect to its violent imagery, Kala is in the rare position of having arguably too much edge. The sound of guns clicking and firing is a boring cliché in the world of mainstream hip-hop, but this record actually makes it scary again. Listening to Kala is practically a moral dilemma, if you consider the context.

But not if you listen to M.I.A. herself. She plays awfully innocent in interviews—to hear her talk about it, her biggest hopes for this record were making something you can dance to and partying with Timbaland in Miami (which she didn't get to do thanks to visa troubles). Can that be true? When she sings "I'm knocking on the doors of your hummer, hummer," is it because she wants to party with you or kill you? Who is this woman?

Well, for one thing, a poet, which gives Kala a lyrical dimension the listener may or not be able to separate from its politics. "I put people on the map that never seen a map/ I show 'em something they ain't never seen/ And hope they make it back," she sings on "20 Dollar." Or the striking visuals of "Paper Planes": "I fly like paper, get high like planes," "a radio in hell just pumping that gas."

On that same song, she shows she's not above playing the cynical opportunist, in a line so perfectly crafted with sound effects it can only be described with onomatopoeia: "All I want to do is bang, bang, bang, bang and click, ching and take your money."

The Sex Pistols tried that 30 years ago. No one believed it then, either.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|