home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | visual arts | review

Collection of Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson

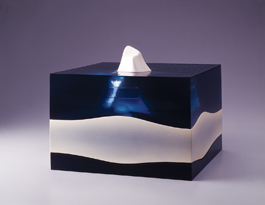

ICE, ICE BABY: Sam Richardson's 1969 sculpture 'Most of That Iceberg Is Below the Water,' anticipates our global-warming worries.

Naturalists

Two shows at the S.J. Museum of Art—'De-Natured' and 'Diebenkorn in New Mexico'—show how artists react to the great outdoors

By Michael S. Gant

AL GORE WINS the Nobel Peace Prize, and all he gets is a boring medallion—and lots of money, glory and, possibly, the Democratic presidential nod. A much better winner's token might be Sam Richardson's cool, prophetic sculpture Most of That Iceberg Is Below the Water, a block of polyester resin shaped like a perfect square chunk of the ocean, frozen and transported to the San Jose Museum of Art.

A white peak rises from the subtly wave-patterned surface; below, spreading out and finally creating a deep strata of white, we see the proverbial "rest of the iceberg." The overhead display lighting creates reflections such that the piece appears to be illuminated from within.

Richardson, an emeritus professor at San Jose State University, created his Iceberg in 1969, but its message resonates with an up-to-date anxiety about global warming and glacial shrinking. We can't freeze time, and eventually there won't be any icebergs above or below the water line.

The Richardson is part of a gallery full of artists' responses to an Earth that increasingly feels threatened by human intervention. The show—"De-Natured: Works From the Anderson Collection"—is divided into loosely defined big-tent categories: "Altered Environment," "Estranged Surroundings," "Mediated Nature" and "Abstracted Nature."

In her catalog essay, subtitled "Beyond the Landscape Tradition," curator Heather Pamela Green attempts to establish a point about how artists have become estranged from the usual nature-awe of traditional landscape painting. The show, however, comes across as somewhat arbitrary (why limit the works to the period from 1968 and 1989?) and takes in more disparate visions than it can easily digest. Just about anything short of a studio portrait qualifies for inclusion.

The color screenprints in Richard Estes' Urban Landscapes series depict anonymous city storefronts, but we have to assume a tension with the absent natural world. Subway II, Red Grooms' gouache and litho crayon on cut-out paper, convincingly creates a 3-D cartoonish tableau of the commuter's life (complete with gun-toting Bernard Goetz figure); this is an extreme case of being "de-natured," I suppose, but it feels utterly out of place in the stated context.

As for Frank Stella's suite of geometric screenprints in H and cross shapes, only the fact that the artist used place names for titles (Telluride, Lake City, etc.) supplies even the remotest hint of nature under strain. I was fascinated by Louise Nevelson's molded-paper piece Dawnscape, in which she impressed abstract shapes in a white-on-white grid, but again, it is a formalist exercise—connecting it to environmental jitters in a post-romantic era takes a real leap of faith.

The show rests on more solid footing in some of its more explicit works. Joseph Goldyne's etching Garbage Can uses delicate lines to depict a reeking dented receptacle leaking noxious fumes, easily chastising us for our failures to be better stewards of the earth. Robert Rauschenberg makes the same argument in his lithograph Earth Day, with a beleaguered bald eagle surrounded by sepia-toned images of rusting cars, trash piles and various crimes against nature. Robert Arneson's Drawing for Ikarus catches the artist's agonized visage (with Arneson, it is always about him) sinking into a monstrous mass of clinging, tangled vines.

As witty as a good political cartoon but scaled to the grandiose proportions of a Hudson River School landscape, William Allan's acrylic Half a Dam delivers what its title promises; the truncated barrier sits impotently across a charging stream while a large salmon contemplates this engineering project gone awry. Even better is Donald Sultan's stunning Factory Fire, August 8, 1985, an overpowering image of a satanic mill in full combustion. Painted with latex and tar instead of pigment, the heavy black bottom half rises to a thick, sticky tower surrounded by soaring yellow flames. This is the way the world ends.

It isn't necessary to stress too much about the curatorial construct of "De-Natured," because there are several real prizes to be enjoyed on their own terms. Two Wayne Thiebaud etchings demonstrate the artist's skill with an ultrafine-point pen as he exaggerates the verticality of San Francisco streets. Roy Lichtenstein's lithograph Sunshine Through the Clouds mixes exuberant brushlike rays of sunshine with passages of uniform stenciled lines suggesting cumulus formations—it positively exudes Vitamin D.

Just as scintillating, Roy DeForest's Hans Bricker in the Tropics sends a boy made of bricks and his cock-eyed bulldog into a palm-tree forest somewhere on the far side of Oz, lavishly decorated with the artist's trademark dimple points of pure pigment. Another Richardson sculpture plants a tiny tree (lifted from some architect's snazzy model, no doubt) in the very center of a long undulated strip of white plastic—possibly the last of its species.

David Hockney's wall-size pool painting, constructed from artfully torn pieces of rag paper loosely fitted together, places a long yellow diving board just above a cool liquid abyss of blue tinted with flecks of green. Even bluer is Ed Ruscha's Shooting Star, a pastel passage of darkest night across which streaks a faint arcing tail of white cosmic dust; just there, in the right corner—look hard—you can see a perfect tiny five-pointed star. This could be the star we wish upon when we wish that the planet might survive our species.

Renatured

In 1950, Bay Area abstract expressionist Richard Deibenkorn moved to New Mexico to work on his master's degree in art. By his own admission, the light and forms of the Southwest desert influenced his developing style. In the large 1952 canvas Untitled (Albuquerque), a narrow sloping horizontal band of red across the bottom certainly evokes a canyon-country mesa, and the massive passage of sandy ochre that dominates the middle of the painting looks like a day in the desert. Albuquerque 7 with four solid bands of color also looks like a geological cut through ancient stones.

With a few exceptions (an ink-sketched beasty dog and the fat black torso known as Disintegrating Pig), the works on display in "Richard Diebenkorn in New Mexico" are pure abstractions, so making direct connections between natural subjects and final product is mostly a guessing game.

The larger canvases are filled with color, marking a move away from the darker moodiness of his early days and hinting at the sharper-edged abstract planes of the Ocean Park series in the late '60s and early '70s. Albuquerque No. 4 (1951), with loose, almost jaunty chunks of green, purple and yellow connected by wavy white ribbons, shows off a playful side of Diebenkorn that eventually got distilled away in favor of pure angles and lines (an example, Ocean Park No. 60, can be seen in the "De-Natured" show).

Some of the most alluring pieces are small-scale, on-the-run exercises. An untitled watercolor on paper from 1951 uses light washes of color punctuated by two sunny orbs. Rapid dashes of ink on muted yellow paper suggest some headless livestock at a gallop. In one compact gouache, a grid of squares and circles (helped out by one long blue line) emerges from a red background so vibrant it looks as if the paper had been soaking in the colored water for a week.

DE-NATURED: WORKS FROM THE ANDERSON COLLECTION and RICHARD DIEBENKORN IN NEW MEXICO, 1950–1952 show through Jan. 6 at the San Jose Museum of Art, 110 S. First St., San Jose. Open Tuesday–Sunday. (408.271.6840)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|