home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | books | review

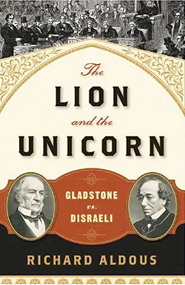

The Lion and the Unicorn: Gladstone vs. Disraeli

Review by Michael S Gant

Throughout the Victorian era, two British statesman dominated their country's politics in a way that Newt Gingrich could only dream of. Gingrich would do doubt identify with Benjamin Disraeli, the Jewish-born (he was baptized as an Anglican) Conservative Party leader, who twice became prime minister, and was famous for his dandyish curls, thinly veiled allegorical novels and sharp tongue. "It was part of his Byronic pose ... to appear both Romantic and cynical at the same time," notes historian Richard Aldous in his dual biography of Disraeli and his lifelong nemesis, William Gladstone (four times prime minister). Disraeli, sharp of tongue and imminently quotable, usually got (and still gets) the better press. "His air was sardonic, urbane and always a little bored," writes Aldous. In the mosh pit of the House of Commons, Disraeli often carried the day with his acid wit and withering put-downs, mostly directed at the brilliant but stolid Gladstone. In or out of power, Disraeli remained Victoria's personal favorite. Gladstone, who started out as a conservative but switched to the Liberal Party midway through his career, rubbed a lot of people the wrong way but at least tried to expand the voting franchise, effect social reforms and criticize British imperialism. In a weird bit of private, pre-Lewinsky kinkiness, Gladstone sought relief from his political labors by trolling the streets looking for prostitutes to "rescue" and afterward engaging in bouts of self-flagellation. The Lion and the Unicorn sometimes bogs down in the well-nigh incomprehensible rat's nest of 19th-century political parties, but Aldous makes a convincing case for this strangest of symbiotic relationships, quoting Lord Elgin: "The melancholy intensity of the former [Gladstone] had found its mirror image in the Mephistophelian nonchalance of the latter [Disraeli]." Unfortunately, sourcing this quote and others is almost impossible given the book's perversely unhelpful footnoting method.

(By Richard Aldous; Norton; 368 pages; $27.95)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|