home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | visual arts | review

Photograph by Dixie Sheridan

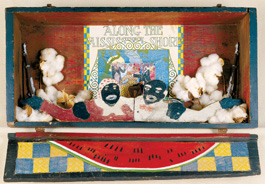

Box of Burdens: Betye Saar's 'De Ol' Folks at Home.'

Family Affair

Betye, Lezley and Alison Saar fashion a complex family tree in paintings, sculptures and assemblages

By Michael S. Gant

LEZLEY SAAR'S large mixed-media work Tale of the Tragic Mulatto presents a strange (and estranged) family tree full of bulbous branches pasted over with photographs, images of runaway slaves, lace cutouts and a lock of hair. One knot in this tree holds a comb, referencing the test by which a person's "race" could be determined by how much resistance her hair gave to a comb.

This remarkable piece reveals much about the family Saar—mother Betye and daughters Lezley and Alison—subjects of a joint show at the San Jose Museum of Art. Rootedness counts, especially family ties. Their paintings, sculptures and assemblages often look across generations, ranging from Lezley's works about her autistic daughter all the way back to the terrors of antebellum times. The lost and the nameless find redemption, and signal figures in the family of black history are reclaimed, as in Lezley's mixed-media portraits Elizabeth Keckley: Mrs. Lincoln's Seamstress and Harriet Hemings: Slave Daughter of Thomas Jefferson.

The rootedness also shows metaphorically in Alison Saar's works, which frequently feature female figures with prominent heads of hair. In the color monoprint 'Taint, thick strands sprout from a woman's head like branches in a dense thicket. For Blonde Dreams, Alison hangs a black female figure craved out of wood from the ceiling by her feet; a braid of brilliant gold hair, longer than the figure itself, dangles to the floor. The contrast sums up centuries of the black/white dichotomy that drives racism.

The family tree also symbolizes the importance of the Saars' complex heritage. Betye's background is African American and Native American and Irish. She married a white man of German, English and Scottish background, creating another layer for her daughters. The endless ebb and flow of racial identity is never far from the family's art. Betye Saar made her name in the early 1970s by confronting racist stereotypes in works like The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (not in this show) and De Ol' Folks at Home. In the latter, a horizontal wood box opens to show a painted watermelon slice on the lid. Inside, a crude wooden cutout depicts Mammy and Uncle Remus arm in arm, surrounded by cotton plants and a some Dixie-nostalgia sheet music for a song called Along the Mississippi Shore. These pieces aren't political or socially subtle, but their artful construction and canny use of found elements keep their assault on complacency fresh.

Betye returned to this blunt style in Supreme Quality (1998), a wood and tin washboard to which is attached a painted figurine of a mammy toting two plastic automatic weapons. Her determined expression emphasizes the message printed across the bottom brace of the washboard: "Extreme times call for extreme measures."

Despite Supreme Quality, Betye Saar's works seem less didactic and more elegiac these days. The 2002 collage Field returns to the familiar trope of cotton—the crop picked by blacks for the gain of whites—in the form of a tiny bale of fiber on the frame, but instead of reworking a stereotypical image of a slave, the artist gives us an old photograph of a sturdy, proud black woman, who looks anything but beaten down, no matter how hard her field labors. She is a real person plucked from the past and given back her individuality.

Throughout her career, Betye Saar has been a superb "assembler" of things. She remembers as a child watching the Watts Towers go up in L.A. and was later deeply influenced by an exhibit of Joseph Cornell's boxes. Shield of Quality (1974) fills a humble wooden box with personal talismans: a white kid glove, a few feathers, a decorative teaspoon. Three old photos show a baby surrounded by two pairs of black women. It's a kind of exalted keepsake, a portal to the past.

All of the Saars exhibit the same attention to discarded objects gathered—rescued really—from the amnesia of junk piles and reanimated through art.

Family Legacies: The Art of Betye, Lezley and Alison Saar shows through Jan. 7, 2007, at the San Jose Museum of Art, 110 S. First St., San Jose. Open Tuesday-Sunday. (408.271.6840)

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|