ANYONE who doesn't yet understand what an unstoppable cultural force YouTube has become should consider this latest bit of news: last week, it was alleged that even while it was pursuing a billion-dollar lawsuit against YouTube's owner Google for copyright infringement, Viacom was secretly uploading promotional videos to the site.

The claim was made by Google in papers filed in federal court in San Jose, just as Silicon Valley prepares to host a showdown on the litigation—philosophically at least—with the "Viacom vs. YouTube" forum, subtitled "The Epic Struggle for Creative Expression," on Thursday, Nov. 6. The highly litigious panel, including YouTube chief counsel Zahavah Levine and Electronic Frontier Foundation senior attorney Fred von Lohmann, will no doubt have differing opinions as to how much the latest twist will affect the Viacom lawsuit. But regardless, when corporate executives suing a supposed copyright pirate recognize that they need that pirate to survive, it does illustrate one very important component of this ongoing saga: how far behind the curve intellectual-property law has fallen in the digital culture of the 21st century.

One man who was making this very argument years before most people even knew the subject existed is Mark Hosler, founder of the pioneering Bay Area–based group Negativland. Negativland's history of making music by pushing the boundaries of sonic form and content opened up the very notion of what "music" was allowed to be in the formerly verse-chorus-verse rock world, paving the way for artists like Danger Mouse, Girl Talk and an entire generation of mashup artists.

And Negativland's history of making art by pushing people's buttons is legendary. Their landmark 1987 album Escape From Noise tweaked American culture and politics with songs like "Time Zones," "You Don't Even Live Here" and "Christianity Is Stupid." Then they pranked the media by connecting the latter song to a real-life ax murder case, which led to their 1989 sound-collage masterpiece Helter Stupid.

In 1991, their controversial "U2" single sucked them into a legal maelstrom in which they were sued by everyone from U2's label Island Records to radio personality Casey Kasem.

Hosler and his band mates turned that experience into perhaps the definitive book on fair use and copyright law, called Fair Use: The Story of the Letter U and the Numeral 2. And as they continued to experiment on albums like 1993's Free, 1997's Dispepsi and 2005's No Business, a funny thing happened: pop culture went Negativland.

From Napster to The Grey Album to YouTube, the very issues Negativland had explored—earning themselves labels like "pirates," "anarchists," "sonic outlaws" and much, much worse in the process—suddenly exploded into the mainstream.

Even weirder, at 46, Hosler has now been embraced as the elder statesman of the digital-culture revolution. He lectures frequently about Negativland's work and fair-use issues, and just last week was invited to Capitol Hill to speak about copyright law.

In true contrarian spirit, meanwhile, Negativland's newest album Thigmotactic is their first collection of "normal" songs—normal by their standards, anyway.

Hosler spoke to Metro before his Capitol Hill trip about YouTube v. Viacom, his new role as remix diplomat and the issues facing digital culture.

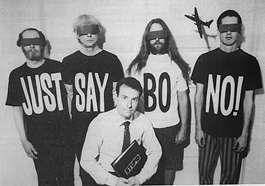

THESE GUYS ARE NOT FROM ENGLAND: The members of Negativland pose with their attorney, Hal Stakke (front and center), after the band was sued by Island Records over their single 'U2.'

METRO: How did you get invited to Capitol Hill to speak about copyright issues?

MASK HOSLER: The Consumer Electronics Association, who represent Microsoft, Apple, Sony, Dell, Panasonic—all the big electronics manufacturers—as well as Google, Yahoo, Verizon ... they have the largest trade show on the planet Earth every year, CES. It turns out that organization and who they represent—the people who make the hardware—want to have all of their systems be as open and portable and allow you as much flexibility as possible for you as the consumer to move your data around. The people who make the content, the movie studios and the music labels—the big ones at least—they want everything as closed as possible. They want strict copy protection. They don't want you to have a DVD and be able to then copy it and put it into all the computers in your house, or transport the data around.

So they're kind of in a war with each other, and it's really over these issues of fair use—what constitutes fair use of intellectual property when you've purchased it? Those folks realized they wanted to educate the public and college students and politicians more about fair use issues, as the years go by, and they're trying to duke this out. 'Cause there's going to be legislation and bills and laws and all that.

Well, they decide to form a sub–lobbying group called Digital Freedom.org. Digitalfreedom.org then realizes, I guess, that fair use issues do extend beyond the hardware into cultural and artistic areas, and they ended up asking Negativland to be on their advisory board a year ago. So with some caution, we agreed.

They said, "We'd love to have you come to D.C., and we'll take you around to some different congressional, Senate and judiciary offices, and there's people who would like to meet you. We want you to put a face to these ideas about culture and art and the reuse and remixing and repurposing of things that's becoming so prevalent." There are people who are interested, but they quite often just don't have a clue about what's going on. You know, they're older, maybe their idea of popular culture is the Rolling Stones. Many of them are Republicans! They don't know what's happening.

What Negativland's seeing happen is that these kind of cultural artistic practices of appropriation have been moving over the last 100 years from the fringes of fine art into music and sound and film, but always being in the fringe, experimental area. And in the last five or six years, particularly in the last couple of years, they've absolutely exploded into the mainstream, where this is now a completely normal practice. A 13-year-old kid is going to take a bunch of corporate logos, and some song he likes, and some animation, a TV show or news footage, maybe something he animated himself, some footage he shot with his friends, and cut it together and make some funny thing.

A CULTURAL OUTLAW IN WASHINGTON, D.C. Decision 2008: The Mark Hosler Edition

The same evolution has happened with your own work and theories. It must feel strange to you to have been on the fringe for so long—considered a prankster and a 'sonic outlaw'—and now be treated like the ambassador of copyright issues.

It's definitely strange. They want me to write a "leave behind"—something that says "this is why I was here," so when I leave they have something to refer to. And I was up all night last night trying to boil down our ideas into something that takes out some of the more strident language that's clearly against giant corporations and pretty much against the whole system of business and politics that we practice in this country. How do I tone it down and yet stay true to who we are? What's the balance there to be struck?

I think if I was trying to do this 15 years ago, I might have had a harder time. It's a good time for me where I am in my life. I feel confident enough about our position and what we're doing that I can modulate it in some way.

Basically, instead of sounding completely crazy to these politicians, I hope I just sound slightly crazy. That's my goal.

Congress may not be too hip, but overall, do you think our culture is becoming more comfortable with the idea that the public rather than artists or corporations have control over any piece of art that can be distributed digitally?

That's a good question, and it depends on who you're talking to. If you're anyone involved with the business of culture and information and media and you're over the age of 25, than maybe no, you're not so comfortable. But if you're younger, well ... I do lectures a lot about our work at universities, and I've been doing it for the last 10 years. I used to have to really explain our whole rationale for why Negativland thought it was OK to appropriate things that we don't own, that we didn't make, and use them in our work. Why in the hell do you think that's OK, that's just stealing! Well, there is a whole explanation I can walk somebody through, and most of the time, in the end, people are convinced. I'm good at convincing them.

But what I'm finding in the last year is that when I'm talking to people in their late teens and early 20s in a university setting, I don't have to explain it anymore. They already know. And it's not even that they know they know, it's just how things are. And that's when things get really interesting. Even though the copyright laws are completely behind the curve here, the practices are becoming so normal that the public is in the driver's seat. The public is going to decide what to do with your logo. In fact, if you're a smart corporation, you don't go sue kids who take your logo and fuck with it on MySpace. You see that as great advertising. You'd be stupid to go after them. I mean, how many times have you had someone forward you what looks to be some weird, screwed-up, homemade video—and it turns out to be an ad for something?

It's bizarre that pranking has become a corporate practice in the digital age.

It's inevitable! When we were doing the stuff we were doing in the late '80s and early '90s, I thought, well, there's going to be some people who are interested in what we do, and are following this type of work and attitude, and they're going to end up in advertising and government. And sure enough, it happened. In fact, some of the staff people of these members of Congress know who we are. They're like, "Oh, I listened to you in college. Cool, we get to talk to the Negativland guy!"

And all of this is in spite of how we've maintained a truly outsider position. Our work is still in a legal gray area, we do everything ourselves, we're totally self-managed. We're total do-it-yourselfers. I still feel like I'm struggling and doing everything in the same way I was doing it when I was a teenager. That doesn't feel any different; it's not any easier, either. But to see that ideas have percolated into people's brains is amazing.

I'm not boasting; I'm involved in making this stuff, but I've also always been an observer and a student of seeing how ideas move from the fringe to the mainstream. The vice president of the Consumer Electronics organization, Michael Petracone, he has a vinyl copy of our "U2" single. I was introduced to the president, and he knew all about our legal cases. And he in fact was the guy who litigated the Sony v. Betamax case—he's that guy!

So even though I may not agree with these guys on their ideas about free trade, it's like, oh my God, these guys are actually kind of the same age as me, and they actually get it. I can have a conversation with them, and I'm not an alien being from another planet. They say, "Oh yeah, we know what you do. Yeah, you're a little bit extreme, but basically we get what you're saying and we understand and, yes, you have a legitimate point of view." That's the shift. Because in the early '90s, when we were talking about this in the wake of the U2 lawsuit, it was like, "Well, you guys are kind of crazy. Why is this even important?"

But as an artist, do you ever struggle with issues of artistic control yourself?

Well, no. People have sampled from us going way back to when sampling started. We would run across records where people had sampled from us. The most famous one was Marky Mark, the actor Mark Wahlberg. He did an album called Music for the People, and it starts off with about five or 10 seconds straight off of our album Escape From Noise ... It's a really stupid, fake white-boy hip-hop record. It's a terrible record. But it sold about a million copies. They did not ask our permission to use it, and I don't care for what they did with it, but our opinion doesn't matter. It's basically none of my business what someone does who appropriates a little bit of our work.

I wonder what someone like Beck, a master repurposer himself, thought of all the repurposing of his work on the album 'Deconstructing Beck.'

He didn't like it! The story of that is that record was curated and put together by the label Illegal Art. It was their first release 10 years ago. Illegal Art is still around; they're the label that's been putting out Girl Talk. Illegal Art put [Deconstructing Beck] out, it came to the attention of Geffen Records, which was Beck's label at the time. Geffen's lawyers were threatening them about the release, saying you can't do this and we're going to sue you.

We heard about it, and we teamed up with RTMark, sort of an early parent group that spawned the Yes Men. We said, hey, if these guys are trying to shut it down, let's go even bigger, let's help you publicize it even more. So RTMark is very good at viral promotion, and then we proposed to Illegal Art, let's reissue it on our label, Seeland Records, Negativland's label. We have a much better distributor than you, we can get this much further out there in the world. And I asked him, for all the trouble this is causing Geffen, now they're getting bad publicity and all this, how many record copies have you sold? And he said "300." That was all it was! It was just that the idea was so disturbing to Geffen.

And you were able to intervene on their behalf?

The first thing we did was send Geffen a letter on behalf of and in defense of the project, and to signal our involvement. We used to be on SST Records, and one of the guys who worked on SST, this guy named Ray Farrell, had moved to Geffen Records along with Sonic Youth. So I contacted Ray and said, "Can you give me the phone number of Beck's management?" I got it, and after they got the letter and we got this really rude and patronizing reply from Beck's lawyer basically saying "Hey, you guys are artists, so what the hell do you know about copyright law?", I called them on the phone and basically just asked them, "What are you people doing? This is no threat to you."

We were hoping that they knew who we were, because by this point we'd gotten a lot of attention for the "U2" single, and it was a shot in the dark but I thought if they happen to know who we are, and if they know that we generated so much bad PR for U2 when Island Records sued us, I wonder if we could use that as leverage to kind of shield this record from getting more hassle. I said, given Beck's background, coming from independent music, and the fact that he samples from all kind of people—and I'm sure he doesn't clear all of his samples either—why is there such a problem?

At that point, the woman told me that Beck had instructed the law team at Geffen to back off—that he thought it was "bad karma," I believe is what she said, to pursue this. I said, that's great, but would he be willing to make a public statement about that, because that would be powerful, if he came out and said, "I'm allowing this to exist."

You have to realize the climate back then was very, very different, it was very tense around these issues. We were looking for any way to move the argument ahead, and getting a big pop star like Beck to kind of sign off on Deconstructing Beck would have been great. Her response was "Well, he doesn't like the record, and he won't do that." I said, it's actually even better that he doesn't like it! He could say, "I don't like it, but it doesn't matter that I don't like it." It's the same thing when we were dealing with U2. We said, if you guys just suddenly got on board and helped us, or reissued our records as a B-side to a U2 single or something creative like that, it would make you look very cool.

Years later, I spoke with Brian Long from Geffen, and was told that one of the main reasons Beck's lawyers backed off really was because of our involvement. They saw it as turning into a big PR nightmare. So our intuition paid off.

Do you think the 'U2' lawsuit would have even existed if you'd put that record out in 2008?

I think probably not. But the record wouldn't have the kind of impact now that it had back then, because appropriation and mashing up and reusing and repurposing things has become so popular and so mainstream. It was the perfect moment to do it; I mean, U2 was absolutely the biggest band on the planet. We put it out because we wanted someone to pick this thing up in a record store and look at it and have this moment of thinking "This thing can't even exist. How could anyone have even done this? And yet, it's in my hand. They did do it. Oh my God."

Now with YouTube, ProTools, iMovie and countless other programs, people not only know it can be done, but are doing it themselves.

Just look at how Girl Talk has emerged with such a vibe of coolness that anyone who gets sampled by him wouldn't want to sue him because they would look so bad, so uncool. As a shield, he's working hard to keep his kind of underground, DIY, whole illegal art thing, and I think that helps to keep people from seeing it as lawsuit bait.

They can't sue everyone who's recut a trailer or a movie on YouTube. The majority of people used to consume films as fantasy, but now they're producers too, inserting themselves into the process.

We're having a much more expanded cultural conversation. And really, regardless of what the laws say or big business thinks, that's just healthy for democracy. That's good for free speech. It's encouraging for people in so many ways. I may be being overly optimistic, but I'd like to think it encourages a little bit of media literacy, in that you're sort of understanding how this stuff works, and how you edit and put things together and "I can do it too."

Again, I might be overly optimistic, but perhaps it means that this priesthood of the experts in media and culture and movie stars and rock stars and all that is taken down a notch, and then another notch, and another notch. In fact, going back to Girl Talk, I think one of the reasons his stuff works is he lets the audience onstage with him, and there's this sense of "Hey, this is just us. I could do that, too, and I'm literally the performer onstage while this guy plays collaged stuff off the laptop that was all made by someone else." Now the reality is, what he's doing is actually so intricate and amazing and brilliant that not everyone could do it. But I think it has that quality to it, like "He's just taking the pop songs on the radio, and I hear them, too! I know what that is!" There's something very democratizing as an experience when I saw his show. It was kind of ultimate punk rock.

It used to be 'anyone can learn to play guitar.' Now anyone can learn to play a laptop, too.

That all dovetails with Beck and things like Napoleon Dynamite—the ascension of geek cool, where the nerd is now sexy. Being the guy who can edit together these sounds on the computer, it's like, you're the star. DJ culture has introduced the idea that a show can be someone just standing there. As Gregg [Gillis, of Girl Talk] mentioned to me, he said, "Can you believe there's a thousand people who will come into a room and watch me just leaning over a laptop, and they think it's a great show! All I'm doing is leaning over my laptop!" Well, and he's sweating. I discovered one of his great tricks—he sweats so much when he performs that he covers his laptop completely with saran wrap before going onstage. He pulled it out when I was backstage with him and was like "I gotta wrap it up before I go out." It's very practical.

Do you think there's any future in Viacom's billion-dollar lawsuit against YouTube?

It's hard to know with that lawsuit: are they for real, or to what degree is it strategic, where they're trying to draw a line in the sand? Maybe they're not expecting to get that much money, they're not expecting it to ever go totally in their favor, but perhaps they're just trying to slow it down in some way. It's like the RIAA [Recording Industry Association of America]. I have spoken to people from the RIAA about all of their different lawsuits, and I said, as an observer, this is a very strange business model where you're suing your customers.

The Viacom lawsuit has gotten strange, too. It was just alleged that even after they sued YouTube they were secretly uploading promotional clips to the site—and not requesting those to be taken down, of course.

I remember thinking two years ago as YouTube was exploding: OK, 2008, the YouTube election. All of a sudden, that ridiculous interview that Sarah Palin gave with Katie Couric, that's just terrifying in what an imbecile she is. Well, I didn't see it. Most people didn't. But a thousand different people uploaded it to YouTube, and that's how I saw it. Went to YouTube, typed in "Palin" and "Couric," and there it is. Or the parody of the Biden/Palin debate on Saturday Night Live. I have a feeling it's going to be argued that that actually had an impact, because you looked at it and thought, "God, this is a comedy show, but that's how she actually is." That was a case where a little bit of comedy may have had an impact in the shifting public perception from her into being someone very dubious. And the story about the vile things that were being said at Palin and McCain rallies by their supporters. I could be wrong, but my impression was that the way that got into the news was that it spread virally on YouTube first. Because the news is paying attention to YouTube. You see YouTube clips used on comedy shows and news shows all the time now. It's interesting when these horribly crappy-looking videos show up on an HDTV show.

In this new landscape, do old-school media companies like Viacom or the RIAA have a chance?

The reality is nothing's black or white. It's not all going to be over tomorrow. But it's like Marshall McLuhan said: major new technologies, when they emerge, can literally destroy existing models of business and power and culture. When radio came along, people thought that no one would go to baseball games anymore because everyone would just listen to them on the radio, and it was going to destroy baseball. It's entirely possible, and I think likely, that we are literally in the middle right now of seeing a whole new way of creating music and culture and getting it out there, and having a so-called career in the arts. It's all being invented out of thin air right now, and it's all being done by individuals and small groups and little companies and do-it-yourselfers.

The 'Viacom vs. YouTube: The Epic Struggle for Creative Expression' forum will be held Thursday, Nov. 6, at the Four Seasons Hotel Silicon Valley, 2050 University Ave., Palo Alto. 5:30pm registration, 6pm program; $20.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.