home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | books | review

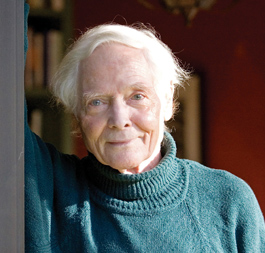

Photograph by Michael Amsler

Lion in Winter: W.S. Merwin says he feels all of 27.

Present in Company

Translator and poet W.S. Merwin muses on the importance of nothing

By Gretchen Giles

ON A SUNNY Saturday afternoon in October, two weeks after his 80th birthday, the poet W.S. Merwin calmly announces that he's just 27—on the inside. Wearing a jaunty hat given to him by the novelist Frank McCourt and dressed in cashmere against the chill that an evening's birthday celebration in wine country promises, Merwin cuts a handsome figure for any age.

Settling into a chair in the library of literary agent Steven Barclay's comfortable home, Merwin says, "Actually, I think that I started realizing that I was me when I was about 3." But the strength of a man at 27—the keenness, the curiosity, the intellect, the mastery—are clearly evident even as Merwin embarks on his ninth decade.

He accepts congratulations on having received the Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry, awarded by the Library of Congress and announced just the day before. He had received the news when returning a call by cell phone at the airport. "That was nice," he says. "I was a judge on it 10 years ago, and I'd forgotten all about it, so I was delighted."

Reminded of Doris Lessing's groceries-in-hand declaration that getting her October Nobel Prize for literature was little more than a "royal flush" in the pantheon of prizes, he smiles. He won the Pulitzer in 1970 for his collection The Carrier of Ladders, gave the money to antiwar protesters and angrily denounced the awarding of honors during wartime. The National Book Award was his in 2005 for the stirring compilation Migration: New and Selected Poems.

"It's pleasant," he shrugs, when asked about prizes. "I think it's terrible for people to count on these things and to attach that kind of importance to them. Ideally, they should have no importance at all other than as a lovely surprise and nothing more. Some people gnaw themselves into little bits wondering if they're going to get one. It's a symptom of something else. I guess I was always pigheaded about being independent."

Indeed. A renowned translator who works deeply in French, Spanish, Latin and Portuguese, Merwin is a poet who has rarely taught, save a short stint at New York City's Cooper Union. Instead, he's stayed outside of traditional academia, becoming the 20th century's primary translator of Dante and bringing such ancient Romantic works as The Song of Roland to new light.

Hymns for His Father

Strictly raised by a Presbyterian minister in New Jersey, Merwin has often said that his first writings were hymns for his father. Entering Princeton at 16, he studied under John Berryman and made friends outside of his provincial circle. He tutored a son of New York's powerful Stuyvesant family during the summer; that led to a job tutoring the son of the great poet, novelist and mythologist Robert Graves.

"And that took me to Europe," Merwin remembers. "And by that time, I had made a tiny bit of money, hundreds of dollars. It wasn't a lot of money; it seemed like a lot, and it was a start.

"All of that," he emphasizes, "was luck." In his early 20s, a favored aunt died and left him a small inheritance, which Merwin used to purchase a house in France that he still visits annually. He has lived in Hawaii for the last 30 years, cultivating rare and endangered palm trees with his wife on 18 ocean-bound acres.

Nominated by W.H. Auden for the Yale Series of Younger Poets Award in 1952, Merwin was acclaimed for his formal style, technical genius and imagistic brilliance. And then he abandoned grammar, causing one reviewer to critique his work in one huge paragraph itself containing no marks save a period at the end.

As some painters gradually move away from representation, painting down to the essence of color, composition and geometry, so has Merwin over the decades rejected the careful training of formalism in favor of poems that contain themselves on the page, forcing the eye to fight the brain for their truest rhythm and meaning. When read as a collection, the poems have the rapid tumble of nature, like being buffeted about by the ocean's relentless, id-less broil.

Odes 'To'

His newest book, the recipient of the Bobbitt award, is 2005's Present Company, a collection of work all told in the second person and masquerading as odes, each one's title beginning with the word "to." But Merwin's interests are catholic and humble, the subjects as varied as "To Billy's Car," "To the Corner of the Eye," "To Prose," "To the Knife," "To Absence"—each subject addressed directly as "you."

"I remember starting [the collection]," Merwin says. "The first one of them was 'To the Unlikely Event,' and it came from being on an airplane for the umpteenth time listening to the speaker say, 'In the unlikely event of a water landing,' and all that airline lingo that they go into, which is a deformation of the English language, and I thought, 'In the unlikely event, what do they mean in the unlikely event?' Everything that we do, every situation we're in, is an unlikely event. They're referring to an unlikely disastrous event, and that's pretty likely too, sooner or later.

"I thought about that poem: imagine the unlikely event; imagine addressing the unlikely event, and then I thought, 'I'd like to write a number of poems that address the unlikely event.' I started to do that, and I realized that I couldn't. The moment you start thinking of it that way, it becomes ... likely. It becomes a sort of invention."

The rich flourishes of Merwin's early work give way in later collections like Present Company to very plain-spoken poetry whose truths are perhaps easier for the casual reader to grasp. "I love things that seem basic, seem very plain, as though it can almost, almost as if nothing's happening," Merwin says.

"I think that my favorite line of poetry in English is, 'Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?' If you think about that line, nobody ever said that. It's simply not ornate and it's not literary, but I'm sure that nobody ever said that, exactly. It's not just spoken English; it is though nothing happened. That's what Mozart was trying to do—it just happened.

I know musicians who say that they're bored with Mozart because he's so predictable and I say, 'Oh, is that so? Nobody ever predicted Mozart!'"

In past interviews, Merwin has described poetry as a form of "paying attention," which he explains is linked to the most basic human drive, that of pleasure. "You know, it's amazing how we have this terrible puritanical background, which is why no one reads poetry in this society, but attention is based on pleasure, which is what we do with music or food or what we like with sexual attraction—it's pleasure, the sensation of pleasure," he says, leaning forward in his chair.

"Think of erotic attention; it comes by itself. You don't feel it because you want to feel it; sometimes you feel it because you shouldn't want to feel it—but it's pleasure. It awakens the attention, and that moment of satisfaction is one of recognition, of recognizing something. It doesn't matter whether it's an abstract painting or someone singing Cosi fan tutte or that line of Shakespeare."

Given Merwin's acute observation about modern Americans and poetry, one wonders about the role of the poet as a leader. Artists have always been looked to as visionaries. After all, he and Haas are appearing together in an environmentally themed presentation titled "On Land and Language." Can poets help to save the earth, its people, our wildlife merely through the art of language? And furthermore, do poets have a responsibility to do so?

Duty to Write

"I think that you'll be happy to know that I don't have any quick glib answer to that," he says with a smile. Citing the French philosopher and writer Albert Camus, he continues, "Those of who can write, meaning those of us who are able to write and those of us who are committed to writing, have a duty to write for ... the unjustly mistreated, whether they're people or not. Animals."

His host quietly enters the room, signaling that it's time for Merwin to grab that jaunty hat McCourt sent him and take off for a night's revels.

"I haven't done enough of it," Merwin assents, though he is known for his vociferous opposition to the Bush administration and the war in Iraq, "but when the occasion presents itself, I think it's important to speak to it. I just wouldn't want to become some sort of professionally drum-thumping writer whose position everybody knows and says, 'Oh, that's just so-and-so.'"

W.S. Merwin could easily live another 80 years, and no one would ever make that mistake.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|