home | metro silicon valley index | movies | current reviews | essay

Dr. No More: Simon Winder argues that Bond has outlasted his usefulness as a cultural icon, but the response to the new 'Casino Royale' film suggests otherwise.

Confessions of a Bond Fanatic

A new book says 007's cultural relevance as the savior of the British Empire and the world is over. But one lifelong fan will never say never again.

By Richard von Busack

I FIND IT hard to understand, but a substantial number of people on this planet have no feelings whatsoever about James Bond. They may enjoy the occasional 007 movie, but then they move on. There may be millions, billions who didn't send virulent emails to one another about the choice of Daniel Craig. Their stomachs didn't twitch when they saw the TV or Internet previews. They remained calm when they heard John Barry's ostinato ramped up for the TV ads with a Carmina Burana-style wordless chorus. And they didn't harbor huge expectations for what would happen when the lights went down right before the opening of Casino Royale.

Luckily, Craig turns out to be the most Bondian Bond since Connery gave it all up for the pleasures of golf. One of the best ad campaigns for 007 was for the benefit of a roundly disrespected Bond impersonator, Timothy Dalton: "His Bad Side Is a Dangerous Place to Be." Craig, too, has a capacious bad side, with loads of room to accommodate world-dominating maniacs. (Speaking of which, what does ELLIPSIS stand for in Casino Royale?) At last, there is no doubt that Daniel Craig is Bond, James Bond. (In 1946's My Darling Clementine, Henry Fonda introduces himself as "Earp. Wyatt Earp." How far back does it go, then, our cinematic infatuation with soft-spoken gunmen?)

In one sense, Casino Royale is just another sequel, or prequel, or rebooting, in a year that's seen too many of them. And this "Bond Begins" film comes out at a time when the publics of the United States and the United Kingdom are burned out on imperial adventures. The New American Century seems over already. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan seem endless.

Bond is a Royal Navy commander working for the British government's Ministry of Defense, known as MI6, the division assigned to take care of covert operations outside the borders of England. So how can a British government killer have a fan base this late in the game, so very long after the empire struck out?

The Man They Couldn't Kill

Some special divinity looks out for the James Bond opuses, more than 50 years since they began. They survived changes in regimes, the fall of the Berlin wall, the rise of feminism and the aging of the many stars who played him. To longtime movie fans, the 007 series is a constant, a link to their remotest movie-watching childhood. Now it's up to younger fans to decide whether the series stands or falls.

"Falls" could be the answer. Unforgiving younger audiences may tire at last of this film's legacy: not just the changing standards of special effects, but the chronic, childish dopiness. That Southern sheriff with the chaw of tobacco. Denise Richards pretending to be a nuclear physicist. Oh hell, that iceberg tidal wave sequence in Die Another Day. Oh shit, that winking concrete whale in the last shot of Licence to Kill.

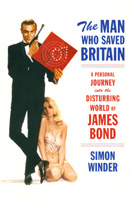

Preceding Casino Royale comes the ultimate Bond re-evaluation, the book The Man Who Saved Britain by Simon Winder (Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 312 pages; $25 cloth). Winder writes that he conceived of his book-length essay as an ADD version of Robert Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy. The book he means is the ultimate discursive classic of the 1600s, the work of an encyclopedic Stuart-era wit trying to compose The Great Big Book of Everything. To quote Burton, Winder's book is "like watermen that row one way and look another." Winder gazes into the past, while he heads into the future, trying to ask himself the question a real Bond geek needs to face: How does that Englishman keep escaping?

Winder begins at the Tunbridge Wells Odeon, where, at age 10, he sees what he is sure is the best movie of his life. (He is imprinted by the fourth-worst James Bond movie, Live and Let Die.) The experience is not ruined much by a bout of puking from the rum-flavored chocos he gobbles as he watches.

The author then rows forward to the vantage point of 2006. From our time, he recalls the England of the 1950-70s, and it's not a pretty sight. His nation was impotent, attacked by the IRA from the outside and by desperate unions and inflation from the inside. At times during the 1970s, the most basic sorts of services went missing—heat, electricity and garbage removal. During this mad decline—"two decades of economic horror"—James Bond, Winder argues, was a solace for a waning England.

Bond's adventures, first in the novels and then onscreen, allowed the harried, broke and bored English to escape their island, even as their upper-class was giving them such a royal sceptering. Currency and travel restrictions persisted long after the war, but there was Our Man, anywhere he needed to be, thanks the miracle of jet travel.

Writes Winder: "In the early films, the Bond theme blares out simply because Bond is going through customs, having got off a plane: a very-far-from-commonplace event for most filmgoers in the early sixties and well worth playing music for."

Thus Fleming becomes the British Empire's last "great memorialist, fantasist and emollient." In his adventures, James Bond recalls the way the Union Jack fluttered from the palms to the pines: there's always a beach scene, always a skiing sequence in the Bond moves, remember.

In the end, Winder imagines a statue of Bond in the old London to go with the various soldiers and statesmen—i.e., killers and finaglers—honored near Trafalgar Square as figures from a long-ago and happily far off era. Like them, Bond fought for his country; like them, Winder argues, Bond is a relic who needs to be put away with all other childish things.

Swankers

To his credit, Winder understands the ignominy of empire. But take it from an American, he really underestimates the point of view of the colonized. The infection stays in the blood. It's resistant to common sense and repeated demonstration of the violence and foolishness of the overlords.

You don't easily override the inner switch that says Cadbury's tastes better than Hershey's or makes you fascinated by the tiny bug-size coat of arms on a tea canister or a booze bottle. It's British! And that makes it swank! Don't believe me? Watch what happens in America the next time the English hold a coronation. No, it won't be a pretty picture for those of us who think the greatest achievement of the United States was becoming citizens instead of subjects.

Americans have a hard time comprehending the gap between the England portrayed in Bond films and the real England. Bernard Lee's M always seemed like such a cool, sober executive. Lee was always meant to recall Winston Churchill, right up to the bow tie. That neckware is still worn by wonkish conservatives prowling the musty halls of the Stanford's Hoover Institute, as a sign by which they may recognize one another.

Winder has to refresh America's memory of how dozy and inept Churchill's leadership was after the war. But here he is, in spirit, in the older Bond movies; just like Daniel Craig has the rough shape of Sean Connery, so does Bernard Lee have the silhouette of Winston Churchill. (And there's a bust of Churchill in M's office, just in case we fail to get the picture.)

M is the first to smell trouble and the last to approve of Bond and his ways. That theme is continued in the new M, Judi Dench, who gently refers to the agent as "a blunt instrument." If there is a Beatles or a Sex Pistols or the lager-drenched oafs of Trainspotting, we Yanks know in our hearts there must be a building with a brass plate reading "Universal Exports," containing a cold-eyed admiral who growls, "Sit down, 007."

Winder hoots at the beginning of the film You Only Live Twice, with a scene set at a summit meeting in which England sits between the United States and the USSR as an equal partner. No, it wasn't likely in 1967. Maybe he fails to understand what England's presence symbolized to the American audience, especially those frightened by the paranoia of the Cold War.

In this escapist fiction, England represented a calm voice saying "Let's put off World War III for a moment, shall we?" In that script—the first where Bond saves the world—the United Kingdom serves the same purpose for U.S. policy that the queen has in Parliament: they can advise, and they can warn.

As the years went by, the Bond film's internationalism defied our cinema's bilateral view of the world. When the Cold War reheated, the 1970s and 1980s Bond movies countered by introducing a humane Russian general named Gogol, played by Walter Gotell in six of the movies. Even before the Berlin Wall fell, Bond films were ahead of the game; from 1964 on, their villains were megalomaniac gangsters who flourished and spread as the Soviet empire waned.

Maybe Bond is too glib. Maybe he's not emotional enough. Maybe that's why we're not supposed to take him seriously. From his viewpoint across the Atlantic, Winder allows action movies having been doing things better in the United States: XxX, for instance, or Die Hard.

Of course, the makers of the James Bond movies have to watch the assignments of Ethan Hunt and Jason Bourne and worry. But there are those of us who would rather watch a bad Bond movie than see Bruce Willis mope or Stallone groan—let alone their heir, a bald beefalo called Vin Diesel, who is the unholy love child of the two actors just mentioned.

First Action Hero

"This time it's personal," say the posters. I'd rather it wasn't. The Bond character—the lethal gent with the gun and the tuxedo—is so watchable precisely because he isn't a rageball. His calm influenced heroes as different in approach as Jackie Chan and Arnold Schwarzenegger, both of whom dressed up as 007 in their films, at one point or another. Part of the staying power of that beloved character is that he unites Cary Grant with Buster Keaton: an unruffled gent who is also a slapstick ace.

The new Casino Royale includes some of the crazy excess of the Bond adventures, but it sails close to the novel; it's brutal, and there is little to laugh at. When rereading 1953's Casino Royale, we can see that Ian Fleming's formula was already in place. What Kingsley Amis called the "Fleming Effect" is in progress. The Fleming Effect is what they call "truthiness": the likely grounding the unlikely. Amid a story of an island castle—a resort for suicides—we get a serious list of the types and effects of poisons in the novel You Only Live Twice. And the book Casino Royale describes the exact smell of a suicide bombing ("Oh yes, that was it, roast mutton.")

As the first Bond novel, Casino Royale was also the first book to flaunt its brands as "the best in the world." During the years from 1953 to his death, in 1964, Fleming name-checked Jamaican Blue Mountain coffee, Brut Blanc de Blanc champagne and Smirnoff's.

The other part of the Fleming Effect is even less savory: an English gentleman's blanket pronouncements upon the less fortunate nations of the world. Some of the few gestalt insults in Casino Royale, the novel: "All French people suffer from liver disease"; "Few of the Asiatic races were courageous gamblers, even the much-vaunted Chinese"; Jews have large earlobes; and so on.

Beyond those dubious details, the novel has a climax that comes early, followed by a coda in which the great intelligencer is out-intelligenced by love. During this endgame, Bond questions the necessity of the hired assassin's mission while he's recovering in the hospital after his encounter with the villain Le Chiffre.

It certainly is questionable, his first mission. Bond is sent to France to break the bank of a Communist moneyman called Le Chiffre, an amnesiac Holocaust survivor who has taken the French word meaning "the number, the cipher" as his name.

Le Chiffre is the Jimmy Hoffa of the day, having embezzled union funds, which he invested in a chain of local brothels. Somehow, he didn't see the "Marthe Richard" law coming, which closed the whorehouses and porn industry in early-1950s France. (And from that day on, France became a beacon of chastity and an encouragement to social legislators everywhere.)

Now seriously in debt, as Fleming writes, "Le Chiffre plans ... to follow the example of most other desperate till-robbers and make good the deficit in his account by gambling." Enter the Secret Service's best card player—but why? Why risk government funds to take out an operative who is already in such trouble? It's like planning the stealthy covert assassination of a stage-four cancer sufferer. Fleming explains that Le Chiffre could be made a communist martyr if he's exposed, but I can't believe the French newspapers would fail to have all due fun with him.

It is not the rock-solid plots that make Bond survive. Some critics talk of the appeal the series has to men, but Ian Fleming once had a large and appreciative female readership. The most scandalous part of rereading Casino Royale is rediscovering how easily Bond falls in love.

One could boil the story into three sentences. First, a description of the sleeping Bond: "ironical, brutal and cold." Second, a comment by the French secret serviceman Mathis, "He's a good-looking chap, but don't fall for him. I don't think he's got much heart." And third, "Like all harsh, cold men, he was easily tipped into sentiment."

James Bondage

Ian Fleming was just that kind of harsh, cold man. The author had dismaying habits. He was a volcanic smoker who drank enough to sink a battleship. Fleming's horribly tempestuous marriage was worsened by the condescension he faced from the literary types he and his wife knew. ("Thunderballs" was Evelyn Waugh's caustic nickname for Fleming.)

Fleming was a fancier of le vice anglais: "He had an enthusiasm for sexual self-punishment," Winder says. As is the case with many practitioners of S&M, Fleming had a heightened appreciation for fantasy and drama, which fits hand in hand with backward politics and immense prejudices. Underneath it all, as Winder concedes, Ian Fleming was "a genuine and thoughtful romantic."

Against the idea of Bond as a cardboard hero, take Kingsley Amis' summing up from his book-length essay The James Bond Dossier. Amis writes, "Those who tend to get into a state about Bond's morals tend to complain that he's very much in bed with someone at the end of each exploit and very much fancy-free at the start of the next, which means he's bad. Or else he's being wish fulfilling in some bad way. The actual breakdown shows that between books he drops only five girls—and all five live abroad. How many other men with his advantages have such a record of moderation?"

In fact, in the novels Bond pursues the exact kind of love life you'd expect from a man who is on the road a lot, who comes back bandaged-up and can't talk about how or why it happened. His romantic life looks like a saga of temporary happiness and long chagrin.

The women were never especially sane, either. Casino Royale's Vesper Lynd (played by Eva Green), with her hot, nervous gaze, magnified by the deepest, darkest eye shadow this side of a vampire movie, may be the best match for the women in the novels in many years.

A couple of Bond's special ladies were getting over having been sexually traumatized. One of them—Miss Pussy Galore—was a big lesbian who changed her mind temporarily, and probably changed it right back as soon as Bond was out of the picture. (A heterosexual lapse can happen to the most solid female girl-fancier. Remember a Two Nice Girls ballad called "I Spent My Last $10 on Birth Control and Beer"?)

Winder winces over the plot of the novel The Spy Who Loved Me, where Bond stops a rape in progress in a New England motel. After the mess is cleared up, Vivienne Michell, who recounts the experience in first person, falls into bed with Our Hero.

This book, dismissed 12 different ways by Winder, was a post-publishing embarrassment to Fleming. Yet Fleming makes something clear that was not at all clear in 1962. There is a difference between rape and sleeping with a man who might be cold and rough. The most valid complaint about the novel, notes Amis sagely, is that Michell unbinds herself too soon.

There are stupidly sexist moments in the Bond films, like the instance in Goldfinger when Sean Connery's 007 slaps the ass of an actress named Margaret Nolan. The books—like the best films in the series—reveal a romantic hero with secret sorrows: a figure more like Bronte's Heathcliff than like Mike Hammer, or the other bruisers of pulp.

Blofeld or Vader?

Winder traces the length of his Bondmania from seeing Live and Let Die until he watches Star Wars. He moved on with his fanaticism. So, also, did most of the movie-watching globe.

I wasn't more sophisticated than the rest of those watchers, but I couldn't follow. Why? Something took hold and wouldn't let go, and grumpy Han Solo and eager-beaver Luke just weren't a substitute.

And now I'll come clean: my workroom includes tiny Bond figures from Gilbert Toys, hand-painted by drunk-on-Mateus Portuguese laborers in 1965. I've also got a maimed but still impressive (impressive to dolts, anyway) Corgi model of "Little Nellie," the teeny, honeybee-striped helicopter from the film of You Only Live Twice.

Around here in easy reach is a shelf of Ian Fleming's moldering pulp (and oh, yes, John Pearson's 1973 biography of 007), and Amis' barely canonical Colonel Sun. Any time I have snarled in print at Matrix-philes or Star Wars oafs or Indiana Jones, I had all these little dust-gatherers silently rebuking me.

And over the years, I had to worry—what the hell was I watching? The sexism, the decadence, the brutal repetition of plot elements was all there, ready to be pointed out by anyone. Last year, I saw some of the 1960s Bonds in a motel in Pennsylvania, and they couldn't have looked worse. I had not only to deal with commercial interruptions and the scorn of my wife ("C'mon, change the channel."), but with those damn advertising graphics dropped in at the bottom of the screen, which make a film look like it's under siege by leprechauns.

While positing Bond as the man who saved his nation, Winder has to deliver up some embarrassing memories. Like the time at boarding school when he and some other naked lads with flashlights tried to re-create Maurice Binder's shadow-ballets under the titles of The Man With the Golden Gun, the second-worst James Bond movie ever made.

As he offers this no-doubt embarrassing reminiscence, I'd like to share mine. Fifteen years later, I can still curl up like a salted slug just thinking of a Sherlock Holmes tour of London I took. When the government offices at Regent's Park were pointed out by the tour guide, I exclaimed, and would not stop exclaiming: "Oh, my God, that's where James Bond works!"

For sniffing the scent of old paperback heroes, in this battered, cold, rough and all-too-real city, I deserved to be called what a street crazy later called me: "You burger-eating Yankee prat."

I can remember my own infection. It began at the Academy Theater in the Tunbridge Wells-like city of Pasadena, Jan. 1, 1970. I was sent there by my mom; she wanted to watch the Rose Bowl on TV with some friends, undisturbed by my usual chatter, accelerated by very speedy asthma drugs.

She picks the movie—"You'll love it," she guesses—and I step over the Rose Parade litter and go inside. I remember the blueness of the titles; a rich royal blue that complemented the pale blue of the day-for-night skiing scenes; I remember the iciclelike electronic keyboards—skeleton-dance music—as Bond travels hand over hand on a cable over the gears of a cable car. I remember the Luciferian knowingness of the villain, a brutal robber who wants to be a count. Lastly, I remember sudden shock of the ending.

That's how quickly a life changes, like a chance bite from the infected mosquito. I saw On Her Majesty's Secret Service and have spent the rest of my life as a film critic, and it was just that simple. I still get malarial recurrences of Bond mania, sometimes during decades when the series wasn't anything in the same neighborhood as cool.

Winder believes that 007 is a has-been, increasingly hard to pass on to the next generation. Is it possible that people go to see Bond films for the same reason that they queue up to see the Rolling Stones in concert: not because of what's going on now, but because of what happened 40 years ago? But I do have an argument against Winder's confusion of the Bond of the Ian Fleming novels with the Bond of the movies.

The spy who came in from the Cold War: There was a lot of controversy when the Bond producers gave the boot to Pierce Brosnan, the first post-Cold-War Bond, but his replacement, Daniel Craig, is a Bond for our times.

Winder dismisses Bond's adventures during the 1990s, with Pierce Brosnan in the lead. Brosnan is a lightweight actor, but his Bond was a complex figure for complex times. When someone as fundamentally nice as Judi Dench calls you "a sexist, misogynist dinosaur," you have to take notice.

He has feelings. He gets drunk by himself in Tomorrow Never Dies, and just like the paperback Bond, he falls in love with a very wrong woman in The World Is Not Enough. And he picks worthy targets, going up against Jonathan Pryce's Elliot Carver, a thinly disguised Rupert Murdoch in Tomorrow Never Dies.

The makers of the upcoming Blood Diamond are already congratulating themselves for taking up the issue of stones got at the cost of great torment. They may have been picking up on Kanye West/Hype Williams' music video on the subject, which derides Shirley Bassey's theme song for Diamonds Are Forever. (At least Shirley Bassey could sing, Kanye.) Bond's opinion of "conflict diamonds" is demonstrated when he blows up several suitcases of the cursed gems in the pre-title of Die Another Day.

And the invisible-car gag in that film—Winder is immensely disgusted by it—is mitigated by the announcement last month that a laboratory has developed a way of cloaking objects from microwave rays, making them invisible to radar. Visible light may be the next step. News reporters with a better memory for Harry Potter than 007 mentioned the cloak of invisibility, but I'd rather think of the device having wheels. And where else could you see an invisible car than in a Bond movie?

Let's look at the record of the Brosnan films, how they updated Bond. Even the least of them boasted the saga's oldest pleasure, the story of a civil servant coming up against rich, protected and powerful criminals. As always Bond fights the power that hides itself in sweet, reasonable and paternal tones—just as we saw during the last election's advertising campaigns. Oh, if just once they'd reveal themselves, as one free-market entrepreneur does, in the course of a Fleming novel: "Mania, my dear Mr. Bond, is as priceless as genius. Dissipation of energy, fragmentation of vision, loss of momentum, the lack of follow through—these are the vices of the herd." Dr. No sat slightly back in his chair. "I do not possess these vices. I am, as you correctly say, a maniac, Mr. Bond. A maniac, with a mania for power. That ... is the meaning of my life. That is why I am here. That is why you are here. That is why here exists."

James Bond, are you a relic? Who really knows, but there sure is a here, here—the kind of here Dr. No is speaking about. And we all know how well international capital becomes indistinguishable from international gangsterism. Think of the cackling of Jack Abramoff on the phone ("Those monkeys!") or Jeff Skilling in his Texas tower. Through either class snobbery or an alcoholic's prickly nerves, Ian Fleming understood just how the game was changing.

Years before a mad billionaire named Osama bin Laden struck out in ways any Bond villain could envy, Fleming created his fictional opposite, a brutal man with a wounded heart. He still walks in the night, accompanied by a gun and an unforgettable phrase of music.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|