home | metro silicon valley index | news | silicon valley | news article

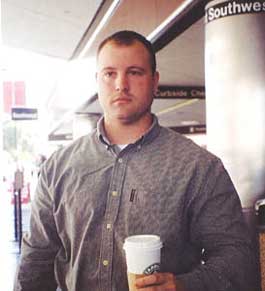

Angle of Repose: In February, Renee Amick of Freedom lost her son, Sgt. Jason Hendrix (pictured here), who was killed by a roadside bomb in Ramadi. She wanted his final resting place to be near her in Watsonville; a judge ordered that his remains be moved to Oklahoma.

The Road to Freedom

It wasn't a huge story when Sgt. Jason Hendrix died in Iraq, but his mother's fight for the right to decide where her son should be buried triggered a national controversy

By Sarah Phelan

TO SAY that 2005 has been a hard year for Renee Amick would be an understatement.

It was on a grim morning in February that the 45-year-old mother of three learned her eldest son, Jason Hendrix, had died in Iraq. Army Staff Sgt. Hendrix, 28, a Manchu Warrior of the Ist Battalion (Mechanized), 9th Infantry Regiment at Camp Ramadi, was killed Feb. 16, she was told, by a roadside bomb that went off after he pulled some fellow soldiers from burning Bradley vehicles.

If that wasn't heartbreaking enough, Amick ends the year at the center of a national controversy, and on the losing end of a battle over where her son's remains should be interred. Based on a call she says Hendrix made to her from Korea on Mother's Day in 2004, she believes he wanted to be buried in Watsonville, near her home in the tiny but famously named Freedom, Calif., north of Monterey.

Unfortunately for Amick, though she was listed as Hendrix's emergency contact on his military papers, her son did not leave a will. That left her at the losing end of the U.S. Army rules, which were written in the 1940s when divorce was relatively rare. Those rules stipulate that if a soldier has no offspring and there is no will, the eldest parent gets custody of the remains.

All of which came up during an ugly custody battle between Amick and her ex-husband, Russell Hendrix, 48, a conflict that began the day after their son's remains were shipped to Watsonville. His body was held there for a month before being rerouted to Oklahoma, where he was buried in April—without Amick being present.

To further compound Amick's sense of loss, her two other children—and by extension her granddaughters—have become estranged from her, as a byproduct of that bitter and publicly fought battle for custody that even brought New York Times reporters to town. Santa Cruz County Superior Court Judge Robert Yonts, in ruling against Amick's request to disinter Hendrix's remains and rebury them in California, ruled that she had failed to prove an "overriding public purpose" for exhuming her son's remains from Tulsa. In a weird twist that she says added insult to injury, Yonts wrote that her tearful testimony during the custody battle "appeared forced and contrived. The tears were not genuine."

Amick calls the judge's assessment "appalling."

A Change in Policy

As hard as 2005 has been, Amick can now say that because of the battle she waged to keep her son's remains in California—and two similar cases in Nevada and Michigan—the Department of Defense has altered its policy on the disposition of remains. In July 2005, the department changed the Record of Emergency Data Form, a.k.a. DD Form 93, to require service members to specify who should receive their remains if they are killed in action.

But Amick, whose congress-member, Sam Farr, along with Nevada Rep. Shelley Berkley, shepherded a bill through the House to codify those changes into law, says she won't rest until the Senate passes a similar bill.

"The law Sam Farr proposed was passed 395-332 in the House; the DD 93 was changed, but it was only adopted as a policy change. I want to make sure it goes to the Senate and becomes law, so that the eldest parent provision is completely eliminated, and it becomes mandatory for soldiers to fill out the DD 93. There's no place for age/gender bias in the 21st century."

Amick says she doesn't want other mothers to go through what she's gone through. "We're talking about a very archaic good ol' boy system, where the man rules and the woman has no voice," she says.

But while Amick doesn't have a lot of respect for what she calls "the higher-ups," she does want it known that she will always support the soldiers, "no matter whether I agree with the war. I always support the sons and daughters of this country for putting their lives on the line."

As for Cindy Sheehan, whose son also died in action in Iraq and who now questions the nobility of that cause, Amick says, "I know where she's coming from. She's just taking it different. She definitely supports the troops. So, if that's what Cindy needs to do, more power to her. I truly believe it's going to take the women of America to speak out to get us out of this mess."

Lost in Ramadi

It was early fall of 2004 when Hendrix was shipped to Ramadi, where he was put in charge of 25 men, many of them still boys in terms of age and experience.

"Jason called himself a highway patrol/medic/father, because he had 25 guys to take care of and had to apply first aid at the scene. He carried morphine and a first-aid kit, so he could administer to them until he could call in helicopters or whatever," says Amick.

She recalls how her son hadn't been in Iraq for two weeks when he had to attend his first funeral.

"He called me on my cell and fell apart on the phone. He talked about how devastating it was, how this war was becoming very real for him and how he was trying to keep it together for his men."

In October, Hendrix called to say he was going to Falluja.

"I basically lost it, but I learned real quick not to do so on the phone," Amick reveals. "Jason made it clear that when he called, he needed support, not negativity. He couldn't handle me having any emotions. So, emotional breakdowns were done to my family and friends."

In Falluja, the calls ceased, until Thanksgiving 2004, when Hendrix phoned from a transit camp.

"Jason was very excited to have some real food," Amick recalls. "In Falluja, they were given five to seven days of rations, which soon ran out. So they had to kill chickens and rats, stick them on rebar, light fires and cook them."

Amick says her son had a couple of near-death experiences during that time: "Inside the mosques, they'd lie on the floor and see lasers pinpointing their bodies. They had to roll over in order not to be hit."

Two weeks after Thanksgiving, Hendrix admitted that he'd gone to see the chaplain about his experiences in Falluja.

"He said he felt better, but had been diagnosed with high blood pressure, and that they were seriously considering shipping him home," says Amick.

She was worried about her son, but also thought that his health problem might be a miracle in disguise.

"At least, if it brought him home and he'd be safe. But another part of me said, 'That's selfish. Jason's destiny is what it is, whether you like it or not.'"

Hendrix called quite a bit in December, saying he was gearing up for special ops in January, because of the Iraqi elections in April 2005.

"He knew he would be dealing with extra insurgent attacks," says Amick.

Every time he called, she could hear mortar rounds in the background.

"Camp Ramadi was getting hit constantly," she says. "Jason said it was important to keep your sense of humor in this war in which there are no safe places, no boundaries, this 360 degrees war."

Rummaging through her photos, Amick searches for the last picture she took of her son, pulling out shots along the way of Jason as a smiling, gangly limbed boy; armed and dangerous in Korea; looking polished in his dress uniform.

"Here it is," she says, retrieving her last photo of Jason, a shot of him at the airport, a cup of Starbucks coffee in hand, his face looking grimly determined as if he knew he was going to his death.

Future Imperfect

From March until the trial in Santa Cruz County this October that came down in favor of her ex, Amick practically lived in her attorney's office—and she still hasn't given up.

"I'll have to see where the legal process goes, but a big law firm in the Bay Area is considering an appeal," she says.

As for the future of Iraq, Amick hopes and prays that the soldiers come home as soon as possible.

"I don't know politics. I don't get involved, but I don't want to go through another year of hearing that they are in harm's way. I'd hate to see anyone live through that stuff. Some soldiers are on their second, third, fourth tour in Iraq. I can't imagine having to watch your kid leave again and go back there, and not know if they are going to come back alive. It's emotional torture."

For now, she is busy making sure that soldiers in Iraq get care packages over the holidays.

"They need to know they are not forgotten," says Amick. Since a box can cost $50-$250 to send—and that's not counting the cost of what's inside—Amick, her daughter and her sister-in-law got involved in asking local community and companies to donate.

"Granite Construction, where my daughter works, donated all the money for the shipment and sent 27 boxes, which arrived right before Christmas 2004."

Amick recently attended a funeral at Mehl's Colonial Chapel, which is where her son's body was originally held before it was shipped to Oklahoma.

"It was very cathartic. In a way, I was burying my son, I just cried my little heart out," says Amick. And while she acknowledges that her ordeal has been very painful, she adds that "in pain, somewhere, is beauty and the lessons to be learned."

"If I can help people locally or nationwide, by telling Jason's story, or righting a wrong, or changing how the military deals with mothers in the future, then I've done my job. I don't regret anything. We said all the 'I love yous,' experienced all the hugs and kisses and all the giggles. No one gets to take that away from me."

Care packages to Hendrix's old unit should be addressed to Cpt. David Harmantas, attn: Task Force Manchu Operation Package, HHC/1-9 In Unit #15154, APO AE o9395-5154.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.