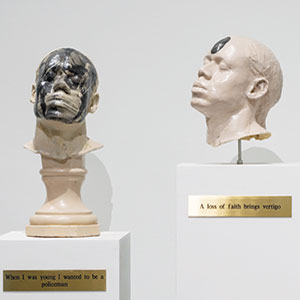

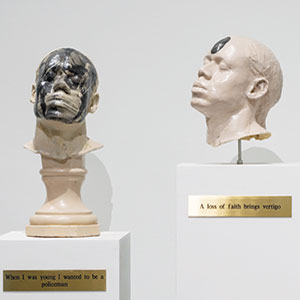

You can hear the sculpture of a head rotating on its axis before you zero in on the location of the whirring sound. It’s one of five heads, each one mounted on its own pedestal. From the entryway, the heads project an alabaster sheen that’s smudged by black ink running across the faces. There are gold plaques underneath each one. Four of them read, “When I was young I wanted to be a policeman.” Beneath the fifth and central figure the plaque reads, “A loss of faith brings vertigo,” which doubles as the name of the entire work itself. That middle head is the whitest of the five except for a significant black oblong blotch marring the forehead. It’s a bullseye that’s lost its shape, melting, molten and dripping down toward the bridge of the nose.

A Loss of Faith Brings Vertigo exemplifies the daring intellectual and emotional range of the sculptures on display in “Michael Richards: Winged” (at the Stanford Art Gallery through March 24). In this survey of work by the late Richards (1963-2001), the black male body is in a state of distress, psychologically and physically torn apart. In an artist’s statement written before his death he said, “In attempting to make this pain and alienation concrete, I use my body, the primary locus of experience, as a die from which to make casts. These function as surrogates, and as an entry into the work.” Marble busts like this usually include their proud subject’s shoulders and chest. In this case, the artist has made a deliberate choice to cut the cast off at the neck.

From up close, you can see that the smudges are actually photo transfers. Each one contains a scene with policemen armed and ready to engage. As the head in the middle spins, you start to put the meaning of the piece together. The photos have been torn from newspaper headlines but they also mirror back to the viewer what these black men encounter and are having to face down. The center figure’s blotch a photo transfer of Rodney King’s face, the 1991 victim of a police beating in Los Angeles could be read as a coagulating wound, the aftermath of a bullet shot through the head. That’s not black ink after all. Literally and figuratively, it’s black blood. These figures have their eyes closed but they aren’t sleeping or at rest they’re wearing death masks.

On the gallery wall behind them, Fly Away O’ Glory pursues that same line of inquiry into bodily detachment. Seven pairs of bronze arms are spread out on the floor. Also mechanized, each arm’s hand clutches a feather that spins helplessly until it stops, only to repeat its absurd and abortive attempt at flight. There’s something Sisyphean about the sculpture. Have hunters shot these “birds” down? They lie on the ground furiously quivering in the throes of death. The sound of the feathers brushing against the ground is disconcerting. You want to pick them up to comfort them or stop the motors to put an end to their misery.

“Michael Richards: Winged” is a poignant exhibit that makes a clear connection between Richards’ artistic obsessions while he was alive and the way that he died at the age of 38 on 9/11. The curators explain that, “On the morning of September 11, 2001, Michael Richards was working in his studio on the 92nd floor of World Trade Center, Tower One, when the first plane struck, taking his life along with thousands of others.” If you’re looking for a facile interpretation of his work, look no further than the recurring flight-related imagery, in the feathers and airplanes. The curators say they have not shaped the show, in choosing these specific sculptures, to make us believe that Richards (unconsciously) foreshadowed the cause of his own death. But there is evidence of his prescience demonstrated in the life-sized statue Tar Baby vs. St. Sebastian.

Standing at attention, Richards is dressed in the uniform of a Tuskegee airman. His full-body cast is made of resin and steel. This statue of a pilot gives off a metallic shine somewhere between bronze and gold. He hovers just above the ground, elevated by a one-foot pole, lifting off from earth toward the heavens. His eyes are closed. His palms are open outward as if in prayer. But that sense of peacefulness is interrupted by eighteen toy-sized bomber planes crashing into his torso. The pilot accepts their arrival in the same way that a man destined for sainthood does, with equanimity. And with a knowingness that Heaven is about to welcome him home, up from the ashes of his preordained disaster.

Michael Richards: Winged

Thru Mar 24, Free

Stanford Art Gallery, Stanford

art.stanford.edu